Position statement

Literacy in school-aged children: A paediatric approach to advocacy and assessment

Posted: Oct 23, 2024

Principal author(s)

Anne Kawamura MD, Angela Orsino MD, Scott McLeod MD, Mark Handley-Derry MD, Linda Siegel PhD, Jocelyn Vine RN BN MHS CHE, Nicola Jones-Stokreef MD; Canadian Paediatric Society, Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Committee

Abstract

Literacy is a key social determinant of health that affects the daily socioemotional lives of children and their economic prospects later in life. Being able to read, write, and understand written text is essential to participating in society, achieving goals, developing knowledge, and fulfilling potential. Yet a significant proportion of adults in Canada do not have the literacy skills they need to meet and manage increasingly complex workforce demands. Paediatric care providers play a pivotal role in identifying children and families at risk for low literacy. This statement offers approaches for assessing children and counselling families to improve reading skills, while advocating for their right to access evidence-based reading instruction.

Keywords: Evidence-based reading instruction; Literacy; Screening

Literacy is a human right

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) recognized literacy as both a human right and an essential prerequisite for a healthy, just, and prosperous world in 2013. An association between having strong literacy skills and higher economic success in adulthood has been well established in the literature[1]. That low literacy skills correlate with lower academic, economic, social, and health outcomes is also well known[1]-[4], and the effects of Canada’s rate of low literacy, which has increased over the past two decades, is being felt even in Alberta and Ontario, provinces with higher literacy scores overall[5]. According to the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), level 3 literacy is typically required to complete high school and do most jobs in Canada[6]. However, recent statistics have shown that 48% of adults have literacy skills falling below this level, while 17% of adult Canadians function at or below the lowest skills level (level 1, or being unable to read a prescription on a medication bottle)[6]. Lower literacy scores are also found in specific populations (e.g., newcomers to Canada, racialized Canadians, and First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples), and otherwise marginalized groups (e.g., incarcerated individuals)[6]-[8].

Reading performance among 15-year-olds in Canada has declined since year 2000[9], with 1 in 7 students scoring at the lowest reading level, as measured in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD’s) Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)[8]. Territories did not participate in 2018 PISA testing and provincial results varied: New Brunswick, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba had lower literacy scores than the national average[8]. Reading difficulties often persist throughout the school years and 1 in 4 children entering grade 1 show significant learning delays compared with their peers[10]. Students from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds or living in households where languages other than English or French are spoken, or who are living with a speech and language delay or a learning difficulty (e.g., a specific learning disorder with impairment in reading), are at highest risk for experiencing low literacy without early, evidence-based instruction and interventions[1]-[4]. The Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC’s) 2022 Right to Read Inquiry Report made 157 recommendations to address inequities related to reading instruction in Ontario[3].

Early literacy development begins in infancy and spans the toddler years. Parents and caregivers promote literacy by reading, speaking, singing, and storytelling with children as part of everyday interactions[11]. Book sharing and storytelling nurture language and literacy while promoting attachment, bonding, and relational skills[11][12]. Attention on written text intensifies after entering grade school, and children who are not reading proficiently by the end of grade 3 are less likely to experience success in all academic areas than more literate peers[9].

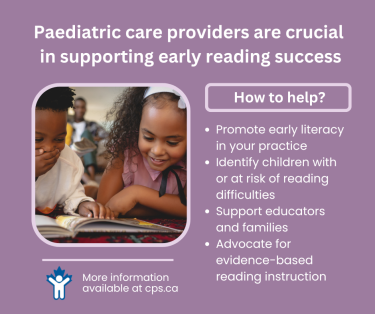

Paediatric care providers are well positioned to help ensure that all children in Canada benefit from in-class reading instruction and literacy skill-building. They can advocate for literacy by collaborating with teachers and other school authorities, child psychologists, and speech-language pathologists to identify children at risk for low literacy, intervene early when needed, and recommend supports at school such that children in their communities achieve optimal, equitable reading achievement.

The science of reading

Accurate and efficient word reading is the basis for skilled reading and critical to comprehending what is read. Research has identified the kind of classroom instruction needed to build optimal, efficient word reading skills in children. Meta-analyses of this research by the National Reading Panel (NRP) in the United States identified the five pillars of classroom reading instruction: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and reading comprehension[13]. (For basic terms and definitions, see Box 1[14][15]). The first three pillars focus on children’s foundational word reading accuracy and fluency skills[13].

Box 1. Terms and definitions

|

Paediatric care providers |

Refers to family physicians, nurse practitioners, general paediatricians, paediatric subspecialists, and other medical professionals providing care to school-aged children |

|

Literacy |

The ability to read, write, and understand written text sufficiently to participate in society, achieve goals, develop knowledge, and fulfill potential |

|

Low literacy |

The inability to read, write, and understand written text at a level required for high school graduation or employment in Canada |

|

Specific learning disorder |

A neurodevelopmental disorder, typically diagnosed in school-aged children, characterized by persistent impairment in at least one area of academic functioning such as reading, written expression, or math |

|

Dyslexia |

A specific learning disorder with impairment in reading |

|

Phonics |

The relationship between written language and the sounds of spoken language |

|

Phonological awareness |

The ability to recognize and manipulate spoken parts of words, including syllables, rhymes, and phonemes |

|

Phonemic awareness |

The ability to recognize and manipulate the smallest units of speech sounds in words (or phonemes, e.g., the word ‘sat’ consists of three phonemes: /s/ /a/ /t/ |

|

Decoding |

The ability to translate a word from print to speech by using knowledge of letter-sound relationships |

|

Whole language or ‘balanced literacy’ |

An instructional approach focusing on the whole word and its meaning. For example, teachers facilitate reading development by providing “rich and authentic reading experiences through immersion in age-appropriate literature”[14] rather than explicit or systematic phonics instruction[15] |

Phonics instruction allows children to learn the sounds associated with letters, which is essential to decoding words. Children also need to learn phonemic awareness, which involves understanding how the smallest units of sound distinguish one word from another, and phonological awareness involves identifying phonemes, blending them together to make words, and segmenting spoken words into constituent phonemes (e.g., the word “sat” is made up of three phonemes: “s”, “ӕ”, and “t”)[13][16].

The NRP report found that systematic phonics instruction yielded better reading gains than non-systematic or non-phonics instructional approaches (e.g., whole language or balanced literacy approaches, or curriculum using cueing systems). Systematic phonics instruction teaches the alphabetic code and how to use it to read words, starting with simple words and sounds and progressing to more complex words and sounds. Systematic phonics instruction is effective when taught through individual tutoring, in small groups, or to whole classes[13][17]. Similar findings in the UK led to national adoption of systematic phonics instruction in 2007[18][19].

The OHRC’s report recommended integrating teaching approaches to bring the science of reading into practice for teaching foundational word reading skills[3]. Systematic phonics instruction appears to work best when initiated early, specifically before rather than following grade 1[13], and phonemic awareness instruction works best when integrated with phonics programming. Children learn both to blend the sounds represented by letters to decode words and to segment words into sounds to spell words[13][16]. One study has shown that a systematic phonics program produced better reading, spelling, and phoneme awareness, with gains being maintained over a 7-year period[3][20][21]. Follow-up reviews of research have supported the NRP’s conclusions: that children from all SES levels make better reading gains when provided with systematic phonics instruction[14][16][22].

In Canada, there is a high prevalence of students who are learning English as a second language, and current data have shown that over half of students from low SES backgrounds and minority groups are not reading at a basic level by the end of grade 4[23]. Phonics and phonemic awareness instruction has proven effective for improving their decoding abilities, especially when implemented in primary school[18][24]-[26].

In-class quality reading programs must include phonemic awareness, phonics, and reading practice to improve word-reading accuracy and speed. Structured literacy resources are available on the Dyslexia Digital Library page at the International Dyslexia Association website. Early reading interventions are needed for children struggling with foundational skills in kindergarten or grade 1 to prevent their falling further behind[17][23]. The OHRC recommends that “interventions should be evidence-based and include systemic, explicit instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics and building word-reading accuracy and fluency”[3]. Intervening early with a core reading skills program could significantly reduce the number of children experiencing low literacy by the end of grade 2[17][23].

At the time of writing, provincial ministries of education in Alberta, Manitoba, New Brunswick, and Ontario were adjusting their early literacy curriculums to prioritize phonics and phonological and phonemic awareness instruction using integrated approaches. Early screening for reading difficulties, monitoring children’s reading skills, intervening appropriately, and ensuring equitable access to evidence-based reading instruction will be required.

What can paediatric care providers do?

Parents seek advice from physicians when children are struggling in school[27] or when they suspect a child’s reading development is not progressing at the same rate as their siblings or peers. Paediatric care providers are in a unique position to identify, support, and advocate for children experiencing or at-risk for reading difficulties because they can provide developmental surveillance and respond early to parents’ concerns.

The research recognizes that both risk and protective factors influence a child’s ability to read[28]. Children with language or articulation disorders, attentional deficits, vision problems, and adverse childhood experiences are at higher risk of having a specific learning disorder with impairment in reading[28], and therefore require special attention to their literacy development. In early environments that lack rich language and literacy experiences or resources, or where children are learning English as a second or third language, learning to read can be especially challenging[29]. An interaction-rich home environment and early, systematic phonics- and phoneme-based instruction in school can mitigate risk for many children[23]. Paediatric care providers are well-positioned to help children and families who are at-risk for or already struggling to read[30] through screening, intervening, support, and advocacy.

Screening

When seeing young children for a regular health visit or who have been referred regarding a reading concern, screen initially for risk by asking a few targeted questions and completing a 2- to 3-minute office-based assessment of reading ability (e.g., DIBELS, Acadience Reading, Table 1). Informal and validated screens that only take a minute to administer are freely available to download online and can be administered to children in almost any office setting (Table 1)[31][32]. At present, tools with adequate validity evidence to screen for reading ability in French are lacking[33]. Current practice is to conduct a detailed history including risk factors for reading difficulties and refer for standardized assessments of reading ability when indicated. Ontario’s Right to Read Inquiry recommends screening for reading difficulties twice a year between kindergarten and grade 2 to identify children with or at risk for reading difficulties and ensuring earlier interventions when required[3]. Paediatric care providers can support families and liaise with a child’s school to recommend interventions, accommodations, and resources. Incorporating screening for reading difficulties into health maintenance guides, such as the Rourke Baby Record or Greig Health Record, could enhance system capacity to identify children at risk for a reading difficulty early on.

Table 1. Identifying early risks for reading difficulties

|

Examples of targeted questions for parents, depending on the child’s age |

Is your child …

|

|

Office-based assessments |

|

|

Standardized screening tools with validity evidence |

|

Information drawn from references 31,32

Diagnosis of specific learning disorder with impairment in reading

Classroom reading curriculums focused on explicit and systematic instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics, and foundational word reading skills, combined with the early identification of risk and prompt and appropriate interventions and support, can prevent or resolve reading difficulties in an estimated 95% of children[23][25][26].

Paediatric care providers commonly recommend a psychoeducational assessment to diagnose a specific learning disorder with impairment in reading or dyslexia in children who struggle with reading. However, the practice may be premature for children in kindergarten and grade 1 (K-1), especially in educational settings where universal (or tier 1) systematic instruction in phonics and foundational word-reading skills is being taught, routine screening occurs, and children have access to timely interventions and support[24]-[26]. It may be more appropriate to refer older students (beyond grade 1) who are not responding to instruction or intervention according to standardized reading test scores for a psychoeducational assessment.

Supporting literacy as part of mental health and developmental care

Literacy is a key social determinant of health that affects the daily socioemotional lives of children, and paediatric care providers must consider the mental health needs of children who struggle with reading[3][34]. Children and adolescents with low literacy skills are known to be at greater risk of experiencing anxiety, low self-esteem, substance misuse, and negative, even aggressive behaviours[35][36], but when care providers encourage them to develop their strengths, while acknowledging how hard they are working to become better readers, it builds confidence and trust, and supports resilience. Paediatric care providers also have essential roles to play in detecting, managing, and monitoring conditions that often co-exist with a specific learning disorder with impairment in reading, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and developmental coordination disorder[37]-[39].

Resources to support literacy development

Educating parents on optimal reading practices and about dyslexia and specific learning disabilities when these conditions are present helps families understand children’s specific needs and how best to support them. Parents may have dyslexia themselves, but encouraging them to read with young children, listen to audiobooks together, and share their own experiences with children when appropriate can promote both literacy and relational health. Online resources for parents that support phonemic awareness and phonics-based approaches can be downloaded at no cost, including the following:

- Abracadabra

- Canadian Children’s Literacy Foundation

- Haskins Global Literacy Hub

- Play Roly

- Reading Rockets

Ontario-based support groups, agencies, school policies, terminology, and other resources can be found in the Physicians of Ontario Neurodevelopmental Advocacy (PONDA) Advocacy Toolkit for Students Struggling to Read[40]. Comparable repositories may need to be developed in other provinces/territories.

Recommendations:

Literacy is a human right, and low literacy in Canada is a serious public health concern. However, paediatic care providers are well-positioned and equipped to improve literacy in young people by:

- Screening regularly at well-child visits between the ages of 4 to 7 years to identify children at risk for reading difficulties and dyslexia.

- Incorporating screening for reading difficulties into health maintenance guides, such as the Rourke Baby Record and Greig Health Record, to enhance system capacity in identifying children at risk.

- Assessing for conditions that commonly co-occur with a specific learning disorder with impairment in reading (e.g., attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and developmental coordination disorder), and monitoring and managing these conditions when present.

- Advocating for enhanced medical training for paediatric and family medicine residents and other paediatric care providers around early literacy, reading difficulties, and learning disabilities.

- Encouraging parents and allied caregivers to read, speak, and sing with infants and young children.

- Educating parents about resources and programs that promote phonemic awareness and phonics-based reading approaches.

- Liaising with schools on behalf of children and families to support their access to reading interventions for children with reading difficulties or a specific learning disorder with impairment in reading.

- Advocating to government, and specifically to provincial/territorial ministries of education, to integrate evidence-based curricular changes, especially phonemic awareness and systematic phonics instruction, into classroom reading curriculums, starting in kindergarten.

- Calling for improved access to classroom instruction and school-based reading interventions that include and benefit children with special needs and other equity-deserving populations: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples, racialized communities, newcomers to Canada, and children living with poverty.

- Supporting government investment in teacher training programs that foster literacy and language in the early years and throughout school life.

Acknowledgements

This position statement was reviewed by the Community Paediatrics Committee, Early Years Task Force, and Developmental Paediatrics Section Executive of the Canadian Paediatric Society.

CANADIAN PAEDIATRIC SOCIETY MENTAL HEALTH AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES COMMITTEE (March 2023)

Members: Anne Kawamura MD (Chair), Johanne Harvey MD, MPH (Board Representative), Natasha Saunders MD, Megan Thomas MBCHB, Scott McLeod MD, Ripudaman Minhas MD, Alexandra Nieuwesteeg MD (Resident Member)

Liaisons: Olivia MacLeod MD (Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry), Angela Orsino MD (CPS Developmental Paediatrics Section), Leigh Wincott MD (CPS Mental Health Section)

Principal authors: Anne Kawamura MD, Angela Orsino MD, Scott McLeod MD, Mark Handley-Derry MD, Linda Siegel PhD, Jocelyn Vine RN BN MHS CHE, Nicola Jones-Stokreef MD

Funding

There is no funding to declare.

Potential Conflict of Interest

Dr. Anne Kawamura reported receiving funding from the Bloorview Research Institute and the Academic Health Sciences Innovation Fund. She is also a member on the Ontario Ministry Advisory Committee for Special Education. Dr. Scott McLeod reported receiving speaker fees from Elvium Pharmaceuticals for a talk on ADHD/ASD. Linda Siegel PhD is a paid consultant to the Ontario Human Rights Commission and unpaid Board member of Play Roly. Jocelyn Vine is a volunteer member of Everyone Reads NS. Dr. Nicola Jones-Stokreef is a past chair of PONDA and a current member of the Physicians of Ontario Neurodevelopmental Disabilities Advocacy and Literacy Alliance of Ontario. Dr. Angela Orsino and Dr. Mark Handley-Derry had no reported conflicts of interest.

References

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD Skills Outlook : First Results from the Survey of Adult Skills. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2013. https://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/Skills volume 1 (eng)--full v12--eBook (04 11 2013).pdf (Accessed June 6, 2024).

- Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police. Literacy and Policing in Canada: Target Crime With Literacy – Fact Sheets 2009. http://en.copian.ca/library/research/police/factsheets/factsheets.pdf (Accessed June 6, 2024).

- Ontario Human Rights Commission. Right to Read: Public Inquiry into Human Rights Issues Affecting Students with Reading Disabilities. 2023. https://www.ohrc.on.ca/sites/default/files/FINAL%20R2R%20REPORT%20DESIGNED%20April%2012.pdf (Accessed June 6, 2024).

- Dewalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19(12):1228-39. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40153.x

- Allison DJ. What International Tests (PISA) Tell Us about Education in Canada. Fraser Institute. September 7, 2022. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/what-international-tests-pisa-tell-us-about-education-in-canada (Accessed June 6, 2024).

- Statistics Canada. Skills in Canada: First Results from the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). Cat. no. 89-555-X. 2023. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-555-x/89-555-x2013001-eng.pdf (Accessed June 6, 2024).

- Mahboubi P, Busby C. Closing the Divide: Progress and Challenges in Adult Skills Development among Indigenous Peoples. C.D. Howe Institute E-Brief, September 2017. https://www.cdhowe.org/ (Accessed June 6, 2024).

- OECD. Country Note, Canada: Programme for Internatioal Student Assessment (PISA) 2018. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2019. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/PISA2018_CN_CAN.pdf (Accessed June 6, 2024).

- O'Grady K, Deussing M-A, Scerbina T, et al. Measuring Up: Canadian Results of the OECD PISA 2018 Study; The Performance of Canadian 15-Year-Olds in Reading, Mathematics, and Science. Toronto, Ont.: Council of Ministers of Education, 2019. https://www.cmec.ca/Publications/Lists/Publications/Attachments/396/PISA2018_PublicReport_EN.pdf (Accessed June 6, 2024).

- Canadian Language and Literacy Research Network, Jamieson DJ. National Strategy for Early Literacy: Summary Report. 2009. http://en.copian.ca/library/research/nsel/summary/summary.pdf (Accessed June 6, 2024).

- Shaw A; Canadian Paediatric Society, Early Years Task Force. Read, speak, sing: Promoting early literacy in the health care setting. Paeditr Child Health 2021;26(3):182-96.

- Williams RC; Canadian Paediatric Society, Early Years Task Force. From ACEs to early relational health: Implications for clinical practice. Paediatr Child Health 2023;28(6):377-93.

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Report of the National Reading Panel--Teaching Children to Read: An Evidence-based Assessment of the Scientific Research Literature on Reading and Its Implications for Reading Instruction. April 2000. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/pubs/nrp/smallbook (Accessed June 6, 2024).

- Fletcher JM, Savage R, Vaughn S. A commentary on Bowers (2020) and the role of phonics instruction in reading. Educ Psychol Rev 2021;33(3):1249-74. doi:10.1007/s10648-020-09580-8

- Fountas IC, Pinnell GS. Guided reading: The romance and the reality. Reading Teacher 2012;66(4):268-84. doi: 10.1002/TRTR.01123

- Brady S. A 2020 perspective on research findings on alphabetics (phoneme awareness and phonics): Implications for onstruction. Reading League J 2020;1(3):20-28.

- Slavin RE, Lake C, Chambers B, Cheung A, Davis S. Effective reading programs for the elementary grades: A best-evidence synthesis. Rev Educat Res 2009;79(4):1391–1466.

- Rose J. Independent Review of the Teaching of Early Reading: Final Report. Nottingham, UK: Department for Education and Skills; 2006. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/id/eprint/5551/2/report.pdf (Accessed June 6, 2024).

- Torgerson C, Brooks G, Gascoine L, Higgins S. Phonics: Reading policy and the evidence of effectiveness from a systematic 'tertiary' review. Res Papers Educ 2019;34(2):208-38. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2017.1420816

- Johnston RS, McGeown S, Watson JE. Long-term effects of synthetic versus analytic phonics teaching on the reading and spelling ability of 10 year old boys and girls. Reading Writing 2012;25(6):1365-84. doi:10.1007/s11145-011-9323-x

- Johnston RS, Watson JE. Accelerating the development of reading, spelling and phonemic awareness skills in initial readers. Reading Writing 2004;17:327-57. doi: 10.1023/B:READ.0000032666.66359.62

- Wheldall K, Buckingham J. Is systematic synthetic phonics effective? Nomanis Notes 2020;14.

- Al Otaiba S, Torgesen J. Effects from intensive standardized kindergarten and first-grade interventions for the prevention of reading difficulties. In: Jimerson SR, Burns MK, VanDerHeyden AM, eds. Handbook of Response to Intervention: The Science and Practice of Assessment and Intervention. New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media; 2007.

- Huo S, Wang S. The effectiveness of phonological-based instruction in English as a foreign language students at primary school level: A research synthesis. Front Educ 2017;2:1-13. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00015

- Lesaux NK, Rupp AA, Siegel LS. Growth in reading skills of children from diverse linguistic backgrounds: Findings from a 5-year longitudinal study. J Educ Psychol 2007;99(4):821-34. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.821

- Lesaux NK, Siegel LS. The development of reading in children who speak English as a second language. Dev Psychol 2003;39(6):1005-19. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.6.1005

- Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA. Dyslexia (specific reading disability). Pediatr Rev 2003;24(5):147-53. doi: 10.1542/pir.24-5-147

- Catts HW, Petscher Y. A cumulative risk and resilience model of dyslexia. J Learn Disabil 2022;55(3):171-84. doi: 10.1177/00222194211037062

- Mascheretti S, Andreola C, Scaini S, Sulpizio S. Beyond genes: A systematic review of environmental risk factors in specific reading disorder. Res Dev Disabil 2018;82:147-52. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2018.03.005

- Hulme C, Snowling MJ. Reading disorders and dyslexia. Curr Opin Pediatr 2016;28(6):731-35. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000411

- Shaywitz SE. Overcoming Dyslexia: A New and Complete Science-based Program for Reading Problems at Any Level. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf; 2003.

- Andrews D, Mahoney W. Children with School Problems: A Physician's Manual. 2nd edn. Toronto, Ont.: John Wiley & Sons; 2012.

- Monetta L, Desmarais C, MacLeod AAN, St-Pierre M-C, Bourgeois-Marcotte J, Perron M. Inventory of Quebec French tools for assessing speech and language disorders. Can J Speech-Language Pathol Audiol 2016;40(2):165-75.

- Arnold EM, Goldston DB, Walsh AK, et al. Severity of emotional and behavioral problems among poor and typical readers. J Abnormal Child Psychol 2005;33(2):205-17. doi:10.1007/s10802-005-1828-9

- Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz JE, Shaywitz BA. Dyslexia in the 21st century. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2020;34(2):80-86. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000670

- Francis DA, Caruana N, Hudson JL, McArthur GM. The association between poor reading and internalising problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2019;67:45-60. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.09.002

- Cohen-Silver J, van den Heuvel M, Freeman S, Ogilvie J, Chobotuk T; Canadian Paediatric Society, Community Paediatrics Committee. Evaluating and caring for children with a suspected learning disorder in community practice (in press).

- Belanger S, Andrews D, Gray C, Korczak D; Canadian Paediatric Society, Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Committee. . Paediatr Child Health 2018;23(7):447-53.

- Ip A, Mickelson ECR, Zwicker JG; Canadian Paediatric Society, Developmental Paediatrics Section. Assessment, diagnosis, and management of developmental coordination disorder. Paediatr Child Health 2021;26(6):366-78.

- Physicians of Ontario Neurodevelopmental Advocacy (PONDA), Jones-Stokreef N. Advocacy Toolkit for Children Struggling to Read 7.0. 2021. https://pondaca.files.wordpress.com/2021/08/advocacy-toolkit-7.08.pdf (Accessed June 6, 2024).

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.