Childhood disability in the 21st century: It’s a whole new ballgame!

Posted on February 10, 2023 by the Canadian Paediatric Society | Permalink

Topic(s):

By Peter Rosenbaum MD, FRCP(C), DSc (HC), FRCPI Hon (Paed) RCPI

Where have we come from?

The 20th century witnessed unprecedented developments in biomedicine in virtually all areas of clinical services. The public’s faith in science was rewarded beyond imagining, with breakthroughs in our understanding of the biological mechanisms of many diseases and the application of that understanding to prevent, treat and increasingly to cure diseases in ways once thought impossible.

The field of childhood neurodisability—the clinical and research focus on neurologically-based impairments that compromise children’s developmental trajectories—has not experienced the same dramatic level of discovery and impact as, for example, childhood cancers or the care of very premature infants. In those areas, a detailed understanding of pathophysiology of the underlying impairments has been applied to create targeted interventions. However, the application of traditional biomedical paradigms—making the right diagnosis and treating accordingly—has been (and indeed still is) found wanting in our field. ‘Diagnosis’ in childhood disability features an alphabet soup of capitalized letters—CP (cerebral palsy), ASD (autism spectrum disorder), ID (intellectual disability), ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), to name but a few—that are, really, descriptive labels for ‘functional impairments’ associated with these ‘conditions’, which in turn are due to a host of often ill-defined underlying biomedical impairments. People have even referred to this mania for diagnosis in our field as ‘adjectives parading as nouns’! There has long been a belief in a ‘non-categorical’ approach to thinking and action—to recognize and act on the commonalities across diagnoses (‘categories’) by blending condition-specific thinking with broader trans-condition ideas as outlined below.

There were numerous remarkable achievements in developmental disability in the 20th century, associated with the opportunity to prevent impairments. We learned about many of the mechanisms that lead to impaired brain function and cause ‘disability’. Dramatic examples include Rh incompatibility leading to kernicterus, maternal iodine deficiency leading to cretinism, the biochemical pathway that leads to phenylketonuria, and polio vaccines. In all these cases, prevention became possible based on this understanding of biomedical pathways. It is easy, now, to take such discoveries for granted, and only consider them when a child unexpectedly presents with conditions like these due, for example, to a failure of screening or immunization.

What has not happened (yet?) are equivalent dramatic biomedical improvements in our ability to treat children with neurodisabilities as we can do for children with type 1 diabetes or the leukaemias. In the field of developmental disability, we have continued to rely on the applications of a wide range of developmental interventions. Therapies include services provided by occupational, physical and speech-language therapists; orthopaedic and neurological surgeries; a host of drugs to address symptoms (e.g., of spasticity, or behavioural dysregulation, or seizures); and a continuing stream of behavioural approaches like applied behavioural analysis (ABA), particularly in the field of autism. Many if not all of these interventions have a place in current management, but none addresses underlying biological impairments, and the evidence of their efficacy is often very limited.

Where are we in 2023?

Based on the introduction to childhood disability outlined above, people might feel discouraged about our field. A frequent perception from outsiders (sadly, including many of our paediatric colleagues) are statements such as: “It must be so sad. You must be so dedicated”. Both sentiments bespeak a fatalistic sense and are often followed by the question: “What can you do for them?”

My response is: “How long have you got (to listen to the answer)?”

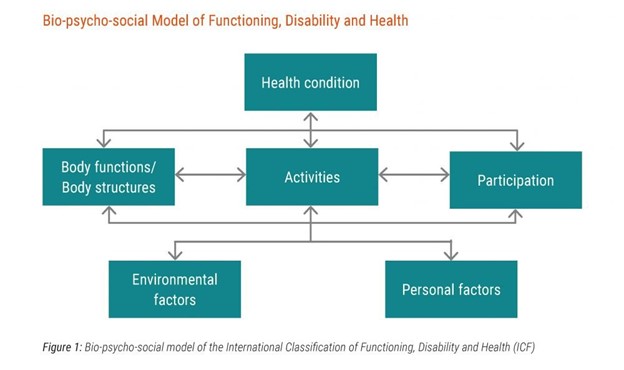

In fact, in the past two decades there has been a huge expansion of our thinking, and our actions, regarding childhood disability. These developments are more conceptual than technical or biomedical and represent an expansion beyond the 20th century’s preoccupation with the latter. We now embrace the World Health Organization’s 2001 framework for health as presented in its International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (aka ICF) (Figure 1). This integrated biopsychosocial framework of interconnected elements reminds us that beyond the diagnosis and the impairments (in ‘body structure and function’) we must consider the impact of a child’s condition on ‘activity’ (doing stuff) and ‘participation’ (meaningful personal engagement with life). We are now expected to pay attention to and include in our formulations both the personal factors that make this child or youth a unique human being, and the environmental factors that shape daily life for everyone.

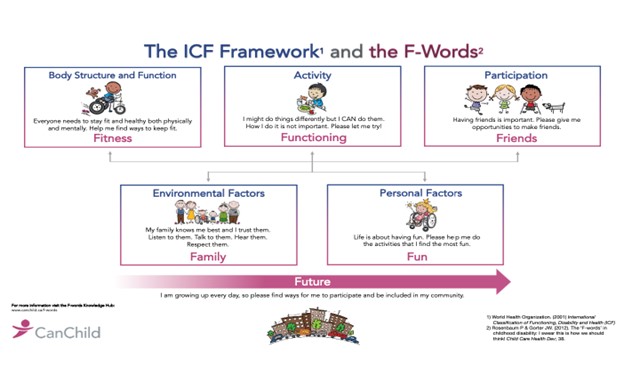

What started as a whimsical effort to bring these ICF ideas to life in our field—the F-words for Childhood Disability (Figure 2), now called the ‘F-words for Child Development’—has captured the attention of parents, colleagues, program managers in child development programs, and policy-makers nationally and internationally. These ideas integrate modern thinking about childhood ‘disability’ in a way that leaves room for the continuing evolution of the biomedical dimensions of conditions that impair child development, while not relying solely on biomedicine. (Readers interested in more detail can visit www.canchild.ca/f-words to access a treasure trove of free resources.)

Let me briefly outline key ideas that form the philosophical backbone of ‘applied child development’. These concepts are hardly new! But what is new are their relative emphases: the shift from cure toward functioning and development, and a recognition that our field is shaking off the constraints of a ‘diagnose-and-treat’ paradigm as the sole approach to the work we do.

Key ideas about the field of childhood disability

The centrality of FAMILY

Paediatrics is increasingly a field where ‘childandfamily’ health is the unifying concept. Yet this statement of the obvious is not applied well enough. Realistically, we almost never see children with problems of health or development on their own. Their issues are all too often encountered as a parent’s or caregiver’s ‘presenting complaint’. The child’s story is told mainly by parents, and the recommendations we make are offered in the context of family, who we hope will apply the best of what we have to offer.

To address developmental disability we now prioritize family and family-centred care. We seek their voices and want to know their values; we depend on their observations about a child’s functioning; we offer advice and make recommendations that we hope or expect to be implemented. Positive family factors are enlisted to help mitigate the physical, mental, social and economic ‘morbidities’ to which they are also too often prone. Recent research evidence from our Canada-Australia group shows that patient and family-centred goals can be achieved!

An emphasis on child (and family!) DEVELOPMENT

The neurodisabilities addressed in our field will likely continue to impact the trajectories of child and family development. But thinking developmentally can change the nature of goals, empowering families (and children) to look to what is important to them without regard to things being done ‘well’ or ‘nicely’. This idea blends directly into the next concept.

A focus on FUNCTIONING – doing stuff!

The traditional goal of developmental intervention was ‘normal’ function—an idea now recognized as both unattainable and, frankly, restrictive. Today we celebrate functioning as a key ingredient in all aspects of child development. We no longer restrict children who do things differently, instead recognizing that achievement leads to further efforts, and that practice makes functioning better (if not perfect)!

A LIFE-COURSE approach…

In the past 20 years, we have begun to recognize a reality that was always there but under-appreciated: children with neurodisabilities will grow to become adults with those conditions. This perspective increasingly influences our thinking and conversations with parents from the earliest days of intervention. There is an exciting emerging field of transition care and longer engagement in the lives of children to prevent them from ‘falling off a cliff’ and disappearing from care services. Much remains to be accomplished, however.

So what?

I strongly believe that the expanded concepts described here have revolutionized child health and should have wider applicability across all areas of paediatrics.

- For services: Identify FAMILY as the key unit of interest, and parents as world experts on their child’s life and condition. Strive to partner with them in accordance with their values and resources. Be guided by their perspectives on child functioning, goals and abilities…

- For teaching: See child development as a basic science in all areas of child health. Good health, neurological integrity, and environmental well-being are leading (though rarely sufficient) contributors to ‘being, belonging and becoming’.

- For research: At clinical and health services levels, there are boundless opportunities to explore the impact of ideas like these on parent, child, and family well-being. We must amass evidence for the effectiveness of things we do on child and family development.

- For policy-making: These ideas have appeal for policy-makers and are being implemented in Canada and internationally. They do not replace the best of what we can do, but they expand the scope of the discourse immeasurably.

Thanks for the opportunity to offer this portrait of the field of modern ‘childhood disability’.

Dr. Peter Rosenbaum is a professor of paediatrics in the Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University, and co-founder of the CanChild Centre for Childhood Disability Research in Hamilton, Ontario. He is a prolific writer and researcher and received the CPS’s prestigious Ross Award in 2000.

Figure 1. WHO’s ICF Framework for Health

Figure 2. The ‘F’-words for child development

Further reading for those interested

-

Rosenbaum PL, Gorter JW. The ‘F-words’ in childhood disability: I swear this is how we should think! Child Care Health Dev. 2012;38(4):457-63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01338.x.

-

Miller AR, Rosenbaum PL. Perspectives on ‘disease’ and ‘disability’ in child health: The case of childhood neurodisability. Front Public Health 2016;4:226. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00226.

-

Rosenbaum P. Childhood disability and how we see the world. Dev Med Child Neurol 2018;60(12):1190. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14008.

-

Rosenbaum. ‘You have textbooks; we have story books’. Disability as perceived by professionals and parents. Editorial. Dev Med Child Neurol 2020;62(6):660. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14491.

-

Rosenbaum P. Developmental disability: Families and functioning in child and adolescence. Front Rehabil Sci 2021;2:709984. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2021.709984.

-

Rosenbaum PL, Novak-Pavlic M. Parenting a child with a neurodevelopmental disorder. Curr Dev Disord Rep 2022;8(4):212-18. doi: 10.1007/s40474-021-00240-2.

-

Miller L, Nickson G, Pozniak K, et al. ENabling VISions and Growing Expectations (ENVISAGE): Parent reviewers’ perspectives of a co-designed program to support parents raising a child with an early onset neurodevelopmental disability. Res Dev Disabil 2022;121:104150. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2021.104150.

Copyright

The Canadian Paediatric Society holds copyright on all information we publish on this blog. For complete details, read our Copyright Policy.

Disclaimer

The information on this blog should not be used as a substitute for medical care and advice. The views of blog writers do not necessarily represent the views of the Canadian Paediatric Society.

Last updated: Feb 14, 2023