Practice point

Update on congenital cytomegalovirus infection: Prenatal prevention, newborn diagnosis, and management

Posted: Sep 9, 2020 | Updated: Jan 24, 2025

Principal author(s)

Michelle Barton, A. Michael Forrester, Jane McDonald; Canadian Paediatric Society, Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee

Updated by: Michelle Barton, Ari Bitnun

Abstract

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the leading cause of congenital infection and the most common cause of non-genetic sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) in childhood. Although most infected infants are asymptomatic at birth, the risk for SNHL and other neurodevelopmental morbidity makes congenital CMV (cCMV) a disease of significance. Adherence to hygienic measures in pregnancy can reduce risk for maternal CMV infection. The prompt identification of infected infants allows early initiation of surveillance and management. A multidisciplinary approach to management is critical to optimize outcomes in affected infants.

Keywords: Congenital infection; Cytomegalovirus (CMV); Neurodevelopmental sequelae; Polymerase chain reaction (PCR); Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL); Valganciclovir

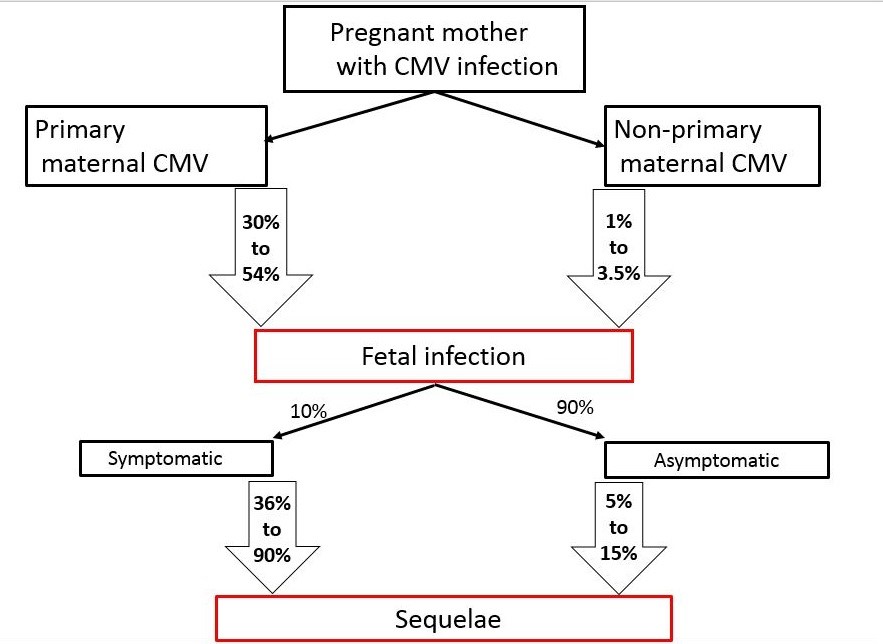

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most common cause of congenital infection, affecting 0.5% to 1% of live births in North America and Europe, and up to 6% of live births in developing countries [1]-[4]. CMV is the leading (up to 25%) cause of non-genetic childhood sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) [5]. The estimated prevalence of long-term neurological sequelae ranges from 5% to 15% in asymptomatic congenital CMV (cCMV) cases, to 36% to 90% [1][6]-[10] in survivors of symptomatic cCMV (Figure 1).

Recent advances in drug therapy for this infection have renewed focus on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment [5][11]. This practice point focuses on the diagnosis of cCMV in infants, and outlines current management strategies. Universal infant screening for cCMV is being considered in some countries, and in Canada, has already commenced in Ontario.

Prenatal maternal infection and risk of fetal transmission

Expectant mothers with primary infection or non-primary (reinfection with different viral strains or reactivation of the primary strain) CMV are at risk of transmitting CMV vertically (transplacentally) to their unborn fetuses [12]-[15]. Rates of transmission are 10- to 15-fold higher in primary compared with non-primary maternal infection (Figure 1) [1][6][10][16]. However, most infected newborns are asymptomatic at birth, with only 10% demonstrating clinical features [5][9][11].

| Figure 1. Rates of fetal infection and sequelae following maternal infection. |

|

CMV is transmitted horizontally through intimate contact with body fluids: saliva, urine, sexual secretions, and breast milk [17]. Among healthy young children in group care or crowded housing situations, opportunities for person-to-person transmission may be higher, thus potentially increasing the prevalence of primary infection. Infected children may continue to shed virus into their pre-school years [18] and are a major source of infection for their adult caregivers (including pregnant women) and other children.

Although administering CMV-specific hyperimmune globulin and antiviral therapy to pregnant women with primary infection may provide benefit, robust evidence to support these interventions is lacking [11][19]-[21]. Developing an effective pre-pregnancy vaccine would likely be the best preventive strategy, but this option is not yet available [22]. Prospective mothers should be educated about hygienic measures, since these have been shown to decrease risk for maternal acquisition [23]-[25] (Table 1).

Approach to investigating and evaluating infants at risk for cCMV

Clinical features of symptomatic cCMV at birth include microcephaly, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), hepatosplenomegaly, petechial rash, jaundice, and seizures (Table 2) [26]-[35]. Infants with symptomatic cCMV should be identified promptly, such that appropriate management can be instituted as early as possible to improve outcomes [36][37]. Diagnostic tests for cCMV rely on directly identifying the virus in an infant’s body fluids before 21 days of age [36][37]. When testing is delayed beyond 21 days, a positive result might indicate perinatal or postnatal infection, and is thus not conclusive for cCMV. Serology is not recommended because, although a negative IgG result can exclude cCMV, a positive result in infancy usually reflects passively transferred antibodies from an infected mother, making it unhelpful in confirming a diagnosis of cCMV [5][38]. Similarly, IgM performs poorly (sensitivity 20% to 70%) as a diagnostic test [39].

|

Physical examination findings

|

|

General: SGA, microcephaly†, jaundice, hydrops†

Skin: Petechiae† Respiratory: Pneumonitis§ Abdomen: Hepatosplenomegaly† CNS: Seizures‡, Poor suck, hypotonia, lethargy Hearing* Eye*: Chorioretinitis†1, optic atrophy, microphthalmia, retinal scars, strabismus, cortical visual impairment‡ |

|

Laboratory abnormalities

|

|

Hematological: Low platelets2 most commonly but other cell line suppression may occur

Transaminitis: Elevated ALT2

Hyperbilirubinemia: Increased conjugated bilirubin2

Spinal fluid abnormalities (not otherwise explained): Pleocytosis, elevated protein, positive CMV PCR‡

|

|

Head imaging abnormalities*1

|

|

Ventricular/Periventricular‡: Calcifications† (50% of CNS abnormalities), ventriculomegaly ± atrophy

Structural‡: Cerebellar/ependymal/parenchymal cysts

Cortical‡: Polymicrogyria

Migrational‡: Lissencephaly, porencephaly, schizencephaly, extensive encephalopathy

Vascular: Lenticulostriate vasculopathy¶

|

|

1. Chorioretinitis and intracranial imaging abnormalities are considered highly supportive features of cCMV. |

Testing using CMV rapid viral cultures (sensitivity >92%, specificity 100%) or PCR-based assays (sensitivity >95%, specificity >98%) of the infant’s urine (preferable method and a bag specimen is adequate) or saliva should be done [40]-[42]. Saliva specimens should be collected by swabbing the inside of an infant’s mouth. Testing should be done more than 1 hour after breastfeeding because shorter intervals may increase false positive results in infants of CMV-infected mothers [41]. All positive saliva specimens should be confirmed with a urine test. In populations where CMV status is unknown but includes children who may not have clinical features of cCMV, the sensitivity of the newborn dried blood spot (DBS) has a wide range (28% to 73%) [43][44]. However, the sensitivity (of 84%) was higher in a meta-analysis that included infants with symptoms compatible with cCMV or those who had already been confirmed to have cCMV [45]. Infants are not necessarily viremic at birth. Therefore, a negative CMV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test of whole blood or plasma, or of newborn DBS, does not exclude CMV [43][44]. A positive DBS result is useful, however, for confirming viremia [43][44][46], and may sometimes be helpful for evaluations that are delayed beyond postnatal age of 3 weeks.

Infants born to mothers with suspected or proven CMV during pregnancy (based on maternal symptoms, serology, fetal ultrasonographic features, or placental histopathology), or infants with risk factors (Table 3) or clinical features compatible with cCMV, should undergo CMV testing and clinical and laboratory evaluation to determine disease classification. Laboratory testing should evaluate for anemia, thrombocytopenia, hyperbilirubinemia, and transaminitis [26]. A negative urine or saliva CMV test should trigger investigations for other congenital infectious or genetic causes (Figure 2).

| Table 3. Identification, diagnosis, and evaluation of infants with cCM |

|

What are the indications for infant testing?

How is cCMV diagnosis confirmed?

How should infants be evaluated when cCMV has been confirmed?

|

|

*Blood or CSF are not recommended as routine tests, but if positive before 3 weeks post-birth, would confirm cCMV. |

| Figure 2. Algorithm outlining testing, referral and treatment of infants suspected to have cCMV is available as a supplementary file. |

Newborns who fail their newborn hearing screen (NBHS) are also being tested for CMV. This more targeted approach allows for earlier detection and management of infants with CMV-associated SNHL [30][47], and has been mandated in some U.S. states [48]. However, targeted screening will not identify those infants who are asymptomatic at birth and pass their newborn hearing assessment but go on to develop late-onset isolated SNHL.

Although universal screening would (ideally) optimize detection of cCMV, consensus is needed concerning the optimal specimen to use for early newborn screening. The range of sensitivity for DBS testing and the additional cost and logistical challenges of using better performing specimens, such as urine or saliva, are unresolved considerations [49].

If infants with suspicion for cCMV with CNS involvement have a lumbar puncture performed to exclude other infectious causes, CMV PCR testing on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can be considered [5]. A positive PCR in CSF offers diagnostic support for CNS disease (Table 3). However, the low sensitivity of PCR and its lack of utility as a prognostic measure make it difficult to recommend routine PCR testing for cases of symptomatic cCMV [50]. When testing has confirmed cCMV, symptomatic infants require ophthalmological and hearing evaluation as well as head imaging (Table 3) [5][11]. For asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic infants, a head ultrasound (HUS) is usually sufficient. Both MRI and CT scan neuroimaging are superior to ultrasound (US) for identifying abnormalities that predict less favourable outcomes [51]. However, MRI is preferred over CT and should be performed in infants with significant neurological features or in those with abnormal findings on US (Table 3), because MRI has the added advantage of being better able to detect findings that predict neurodevelopmental morbidity (e.g., dysplasia of hippocampus and cerebellum, and polymicrogyria) (Table 3) [52].

Management approach based on symptom severity

Cases of cCMV are classified at or around the time of birth by symptom severity as asymptomatic, mild, and moderate to severe disease (Table 4) [11][53]. Because the timing of symptom assessment and severity staging precedes audiological assessment, the currently accepted symptom-based classification makes no reference to the presence of SNHL.

| Table 4. Essential points for disease classification, referral, treatment recommendations, and follow-up |

|

How are infants classified?

Confirmed: Positive ’gold standard’ test* before 3 weeks OR newborn DBS-positive

Asymptomatic ± SNHL‡

Mildly symptomatic ± SNHL

Moderate-to-severely symptomatic ± SNHL

Probable§: Positive ‘gold standard’ test* after 3 weeks PLUS CMV-specific features (Table 2)

Who should be referred to an infectious disease specialist?

Who should be treated?

What is the recommended treatment?

What does follow-up entail?

|

|

*‘Gold standard’ test refers to CMV PCR/CMV viral culture of urine OR saliva CMV PCR in non-breastfed infants. A positive saliva CMV PCR test requires confirmatory urine CMV testing in breastfed infants. |

Asymptomatic disease

There is no evidence to support antiviral therapy for asymptomatic CMV disease without SNHL at the present time. However, asymptomatic infants require regular audiological evaluation, with prompt ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist referral if SNHL is detected. Expert opinions differ regarding treatment of infected infants with isolated SNHL [11][37]. Definitive recommendations await results of ongoing trial, but existing observational data suggest benefit [54].

Mild disease

Mild CMV is characterized by transient or minor abnormalities in one or two organ systems, with no CNS involvement. Managing mild CMV cases who are later confirmed to have SNHL should involve ID consultation [11][37]. Management may be individualized, taking into consideration the presence and severity of SNHL [11][27] (Figure 2).

Moderate to severe disease

All moderate to severe CMV cases (defined in Table 4) [53] should be referred promptly for infectious disease consultation. Data from two trials have provided support for treating severely symptomatic infants with antiviral agents [55][56]. The more recent trial demonstrated improved neurodevelopmental and hearing outcomes for infants treated for 6 months as compared with for 6 weeks [56]. Oral valganciclovir should be administered for 6 months. Parenteral ganciclovir may be substituted for the first 2 to 6 weeks of treatment when the infant is very ill [5][57].

Adverse effects (AEs) of antiviral therapy include neutropenia [29], thrombocytopenia, transaminitis, and elevated urea and creatinine levels. While on therapy, infants need to be monitored serially for AEs (Table 4). There is no evidence to support routine viral load monitoring, as viral loads do not consistently correlate with treatment response [28][56].

Follow-up and monitoring for sequelae (Table 4)

In addition to ongoing hearing and neurodevelopmental evaluation and ophthalmological follow-up [2][58], close dental follow-up may also be needed. Enamel hypoplasia has been reported in up to 40% of children with symptomatic CMV [59][60]. Evidence for a high prevalence of vestibular dysfunction in children with cCMV, even those without SNHL, is growing, which indicates that occupational therapy may also be of benefit [61].

Late-onset, progressive SNHL has a median onset of 27 months of age, but has been reported to develop as late as 44 months of age [30]. Serial hearing evaluations should be conducted regularly over the first 4 to 5 years of life [30]. Children with extensive CNS involvement may experience seizures, cerebral palsy, and intellectual delay (Table 5) [17][62]-[64]. They require neurodevelopmental follow-up and appropriate multidisciplinary support.

|

|

Frequency (%) in infants

symptomatic at birth |

|

Any sequelae

|

36 to 90

|

|

Microcephaly

|

35 to 40

|

|

Severe motor deficits

|

15 to 25

|

|

Neurodevelopmental

|

42

|

|

Cognitive deficits

|

50 to 70

|

|

Seizures

|

15 to 20

|

|

Any SNHL

|

27 to 69

|

|

Unilateral SNHL

|

19

|

|

Bilateral SNHL

|

50

|

|

Ocular abnormalities

|

25 to 50

|

|

Visual impairment

|

22 to 58

|

Conclusion

cCMV is the leading cause of non-genetic SNHL and a significant cause of neurodevelopmental and neurosensory morbidity. Basic hygienic measures are highly effective in preventing maternal infection and should be promoted in antenatal care. Early laboratory identification of infants with cCMV (within the first 21 days after birth) is essential to determine disease severity and initiate antiviral therapy in moderate to severe cases. All infants with symptomatic cCMV and asymptomatic infants with isolated hearing loss should be referred to an infectious disease specialist. When indicated, valganciclovir therapy, initiated in the neonatal period and administered for 6 months, has been shown to improve hearing and developmental outcomes. Affected infants require multidisciplinary follow-up. Future research should address newborn screening, treatment outcomes in children with isolated SNHL or mild disease, CMV vaccine development, as well as diagnostic and prognostic strategies.

Addendum

Since the writing of this guideline, new evidence has emerged for antiviral treatment of congenital CMV associated with isolated sensorineural hearing loss [65]. Although the recent study cited below was not randomized and is limited by small sample size, it did find that oral valganciclovir treatment initiated before infants with congenital CMV reached 13 weeks of age was associated with better hearing outcomes at 18 to 22 months of age. Based on these results, both European [66] and American [67] guidelines have recommended valganciclovir therapy for 6 weeks in infants younger than 3 months of age with congenital CMV-associated isolated sensorineural hearing loss. For moderate to severely symptomatic CMV, chorioretinitis, or central nervous system disease, therapy should be initiated as early as possible but may be commenced as late as 13 weeks of life [67].

Acknowledgements

This practice point was reviewed by Dr. Soren Gantt (University of British Columbia, B.C. Children’s Hospital Research Institute) and Dr. Wendy Vaudry (University of Alberta, Stollery Children’s Hospital), with our thanks. It has also been reviewed by the Community Paediatrics, Drug Therapy and Hazardous Substances, Fetus and Newborn, and Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Committees of the Canadian Paediatric Society.

CANADIAN PAEDIATRIC SOCIETY INFECTIOUS DISEASES AND IMMUNIZATION COMMITTEE (2020)

Members: Michelle Barton MD; A. Michael Forrester MD (past member); Ruth Grimes MD (Board Representative); Nicole Le Saux MD (Chair); Laura Sauve MD; Karina Top MD

Liaisons: Tobey Audcent MD, Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT), Public Health Agency of Canada; Sean Bitnun MD; Canadian Pediatric and Perinatal HIV/AIDS Research Group; Fahamia Koudra MD, College of Family Physicians of Canada; Marc Lebel MD, IMPACT (Immunization Monitoring Program, ACTIVE); Yvonne Maldonado MD, Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics; Jane McDonald MD, Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada; Dorothy L. Moore MD, National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI); Howard Njoo MD, Public Health Agency of Canada

Consultant: Noni E MacDonald MD

Principal authors: Michelle Barton MD, A. Michael Forrester MD, Jane McDonald MD

Updated in January 2025 by: Michelle Barton MD, Ari Bitnun MD

References

- Kenneson A, Cannon MJ. Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Rev Med Virol 2007;17(4):253–76.

- Vaudry W, Lee BE, Rosychuk RJ. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection in Canada: Active surveillance for cases diagnosed by paediatricians. Paediatr Child Health 2014;19(1):e1-5.

- Lanzieri TM, Dollard SC, Bialek SR, Grosse SD. Systematic review of the birth prevalence of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in developing countries. Int J Infect Dis 2014;22:44–8.

- Pass RF, Arav-Boger R. Maternal and fetal cytomegalovirus infection: Diagnosis, management, and prevention. F1000Res 2018;7:255.

- Gantt S, Bitnun A, Renaud C, Kakkar F, Vaudry W. Diagnosis and management of infants with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Paediatr Child Health 2017;22(2):72–4.

- Pass RF, Fowler KB, Boppana SB, Britt WJ, Stagno S. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection following first trimester maternal infection: Symptoms at birth and outcome. J Clin Virol 2006;35(2):216–20.

- Dollard SC, Grosse SD, Ross DS. New estimates of the prevalence of neurological and sensory sequelae and mortality associated with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev Med Virol 2007;17(5): 355–63.

- Lopez AS, Lanzieri TM, Claussen AH, et al. Intelligence and academic achievement with asymptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatrics 2017;140(5):pii:e20171517.

- Soper DE. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: An obstetrician’s point of view. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57 Suppl 4:S171-3.

- Simonazzi G, Curti A, Cervi F, et al. Perinatal outcomes of non-primary maternal cytomegalovirus infection: A 15-year experience. Fetal Diagn Ther 2018;43(2): 138–42.

- Rawlinson WD, Boppana SB, Fowler KB, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy and the neonate: Consensus recommendations for prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17(6): e177–e188.

- Yamamoto AY, Mussi-Pinhata MM, Boppana SB, et al. Human cytomegalovirus reinfection is associated with intrauterine transmission in a highly cytomegalovirus-immune maternal population. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202(3):297.e1-8.

- Wang C, Zhang X, Bialek S, Cannon MJ. Attribution of congenital cytomegalovirus infection to primary versus non-primary maternal infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52(2):e11-3.

- Britt W. Controversies in the natural history of congenital human cytomegalovirus infection: The paradox of infection and disease in offspring of women with immunity prior to pregnancy. Med Microbiol Immunol 2015;204(3):263–71.

- Britt WJ. Congenital human cytomegalovirus infection and the enigma of maternal immunity. J Virol 2017;91(15):pii:e02392-16.

- van Zuylen WJ, Hamilton ST, Naing Z, Hall B, Shand A, Rawlinson WD. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: Clinical presentation, epidemiology, diagnosis and prevention. Obstet Med 2014;7(4):140–6.

- Friedman S, Ford-Jones EL. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection - An update. Paediatr Child Health 1999;4(1):35–8.

- Cannon MJ, Hyde TB, Schmid DS. Review of cytomegalovirus shedding in bodily fluids and relevance to congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev Med Virol 2011;21(4):240-55.

- Revello MG, Lazzarotto T, Guerra B, et al. A randomized trial of hyperimmune globulin to prevent congenital cytomegalovirus. N Engl J Med 2014;370(14):1316–26.

- Blázquez-Gamero D, Galindo Izquierdo A, Del Rosal T, et al. Prevention and treatment of fetal cytomegalovirus infection with cytomegalovirus hyperimmune globulin: A multicenter study in Madrid. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2019;32(4):617-25.

- Seidel V, Feiterna-Sperling C, Siedentopf JP, et al. Intrauterine therapy of cytomegalovirus infection with valganciclovir: Review of the literature. Med Microbiol Immunol 2017;206(5):347–54.

- Pass RF, Zhang C, Evans A, et al. Vaccine prevention of maternal cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med 2009;360(12):1191–9.

- Vauloup-Fellous C, Picone O, Cordier AG, et al. Does hygiene counseling have an impact on the rate of CMV primary infection during pregnancy? Results of a 3-year prospective study in a French hospital. J Clin Virol 2009;46 Suppl 4:S49-53.

- Adler SP, Finney JW, Manganello AM, Best AM. Prevention of child-to-mother transmission of cytomegalovirus among pregnant women. J Pediatr 2004;145(4):485–91.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CMV Fact Sheet for Pregnant women and Parents. September 2018: https://www.cdc.gov/cmv/fact-sheets/parents-pregnant-women.html (Accessed February 6, 2019).

- Boppana SB, Pass RF, Britt WJ, Stagno S, Alford CA. Symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection: Neonatal morbidity and mortality. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1992;11(2):93–9.

- Demmler GJ. Screening for congenital cytomegalovirus infection: A tapestry of controversies. J Pediatr 2005;146(2):162–4.

- Ross SA, Novak Z, Fowler KB, Arora N, Britt WJ, Boppana SB. Cytomegalovirus blood viral load and hearing loss in young children with congenital infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009;28(7):588–92.

- Amir J, Wolf DG, Levy I. Treatment of symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection with intravenous ganciclovir followed by long-term oral valganciclovir. Eur J Pediatr 2010;169(9):1061–7.

- Fowler KB. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: Audiologic outcome. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57 Suppl 4: S182-4.

- Coats DK, Demmler GJ, Paysse EA, Du LT, Libby C. Ophthalmologic findings in children with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. J AAPOS 2000;4(2):110-6.

- Hebbal P, Russell BK, Akande T, Niazi M, Hagmann SH, Purswani MU. Disseminated congenital cytomegalovirus infection presenting as severe sepsis in a preterm neonate. J Pediatr 2016;170:339-e1.

- Rai N, Thakur N. Congenital CMV with LAD type 1 and NK cell deficiency. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2013;35(6):468-9.

- Irizarry K, Honigbaum S, Demmler-Harrison G, Rippel S, Wilsey M. Successful treatment with oral valganciclovir of primary CMV enterocolitis in a congenitally infected infant. Fetal Pediatr Pathol 2011;30(6):437-41.

- Lee-Yoshimoto M, Goishi K, Torii Y, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus pneumonitis and treatment response evaluation using viral load during ganciclovir therapy: A case report. Jpn J Infect Dis 2018;71(4):309-11.

- Ross SA, Novak Z, Pati S, Boppana SB. Overview of the diagnosis of cytomegalovirus infection. Infect Disord Drug Targets 2011;11(5):466–74.

- Luck SE, Wieringa JW, Blázquez-Gamero D, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus: A European expert consensus statement on diagnosis and management. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2017; 36(12):1205–13.

- Bilavsky E, Watad S, Levy I, et al. Positive IgM in congenital CMV infection. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2017;56(4):371–5.

- Revello MG, Gerna G. Diagnosis and management of human cytomegalovirus infection in the mother, fetus, and newborn infant. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002;15(4):680-715.

- Balcarek KB, Warren W, Smith RJ, Lyon MD, Pass RF. Neonatal screening for congenital cytomegalovirus infection by detection of virus in saliva. J Infect Dis 1993;167(6):1433–6.

- Boppana SB, Ross SA, Shimamura M, et al. Saliva polymerase-chain-reaction assay for cytomegalovirus screening in newborns. N Engl J Med 2011;364(22):2111–8.

- Ross SA, Ahmed A, Palmer AL, et al. Detection of congenital cytomegalovirus infection by real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis of saliva or urine specimens. J Infect Dis 2014;210(9):1415–18.

- Boppana SB, Ross SA, Novak Z, et al. Dried blood spot real-time polymerase chain reaction assays to screen newborns for congenital cytomegalovirus infection. JAMA 2010;303(14):1375–82.

- Vives-Oñós I, Codina-Grau MG, Noguera-Julian A, et al. Is polymerase chain reaction in neonatal dried blood spots reliable for the diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus infection? Pediatr Infect Dis J 2018;38(5):520-4.

- Wang L, Xu X, Zhang H, Qian J, Zhu J. Dried blood spots PCR assays to screen congenital cytomegalovirus infection: A meta-analysis. Virol J 2015;12:60.

- Soetens O, Vauloup-Fellous C, Foulon I, et al. Evaluation of different cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA PCR protocols for analysis of dried blood spots from consecutive cases of neonates with congenital CMV infections. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46(3):943–46.

- Ari-Even Roth D, Lubin D, Kuint J, et al. Contribution of targeted saliva screening for congenital CMV-related hearing loss in newborns who fail hearing screening. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2017;102(6):F519-24.

- Newborn Screening Ontario. Hearing Screening FAQ: https://newbornscreening.on.ca/en/page/hearing-screening-faq (Accessed February 7, 2020).

- Schleiss MR. Congenital cytomegalovirus: Impact on child health. Contemp Pediatr 2018;35(7):16–24.

- Goycochea-Valdivia WA, Baquero-Artigao F, Del Rosal T, et al. Cytomegalovirus DNA detection by polymerase chain reaction in cerebrospinal fluid of infants with congenital infection: Associations with clinical evaluation at birth and implications for follow-up. Clin Infect Dis 2017;64(10):1335-42.

- Giannattasio A, Bruzzese D, Di Costanzo P, et al. Neuroimaging profiles and neurodevelopmental outcome in infants with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2018;37(10):1028-33.

- de Vries LS, Gunardi H, Barth PG, Bok LA, Verboon-Maciolek MA, Groenendaal F. The spectrum of cranial imaging and magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities in congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Neuropediatrics 2004;35(2):113-9.

- Kadambari S, Williams EJ, Luck S, Griffiths PD, Sharland M. Evidence-based guidelines for the detection and treatment of congenital CMV. Early Hum Dev 2011;87(11):723-8.

- Pasternak Y, Ziv L, Attias J, Amir J, Bilavsky E. Valganciclovir is beneficial in children with congenital cytomegalovirus and isolated hearing loss. J Pediatr 2018;199:166-70.

- Kimberlin DW, Lin CY, Sánchez PJ, et al. Effect of ganciclovir therapy on hearing in symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus disease involving the central nervous system: A randomized, controlled trial. J Pediatr 2003;143(1):16–25.

- Kimberlin DW, Jester PM, Sánchez PJ, et al. Valganciclovir for symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus disease. N Engl J Med 2015;372(10):933–43.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Cytomegalovirus Infection. In: Kimberlin DW, Brady M, Jackson MA, Long S, eds. Red Book 2018-2021: Report of the Committee on Infectious Disease, 31st edn. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2018.

- Boppana S, Amos C, Britt W, Stagno S, Alford C, Pass R. Late onset and reactivation of chorioretinitis in children with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1994;13(12):1139–42.

- Stagno S, Pass RF, Thomas JP, Navia JM, Dworsky ME. Defects of tooth structure in congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatrics 1982;69(5):646-8.

- Stagno S, Pass RF, Dworsky ME, Britt WJ, Alford CA. Congenital and perinatal cytomegalovirus infections: Clinical characteristics and pathogenic factors. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser 1984;20(1):65-85.

- Bernard S, Wiener-Vacher S, Van Den Abbeele T, Teissier N. Vestibular disorders in children with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatrics 2015;136(4):e887-95.

- Dreher AM, Arora N, Fowler KB, et al. Spectrum of disease and outcome in children with symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection. J Pediatr 2014;164(4):855-9.

- Jin HD, Demmler-Harrison GJ, Coats DK, et al. Long-term visual and ocular sequelae in patients with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2017;36(9):8777-882.

- Schleiss MR. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: Update on management strategies. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2008;10(3):186-92.

- Chung PK, Schornagel FAJ, Soede W, et al. Valganciclovir in infants with hearing loss and clinically inapparent congenital cytomegalovirus infection: A nonrandomized controlled trial. J Pediatr 2024;268:113945. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2024.113945

- Leruez-Ville M, Chatzakis C, Lilleri D, et al. Consensus recommendation for prenatal, neonatal and postnatal management of congenital cytomegalovirus infection from the European congenital infection initiative (ECCI). Lancet Reg Health Eur 2024;40:100892. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2024.100892. Erratum in: Lancet Reg Health Eur 2024;42:100974. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2024.100974

- American Academy of Pediatrics [Cytomegalovirus infection] In: Kimberlin DW, Banerjee R, Barnett ED, Lynfield R, Sawyer MH, eds. Red Book 2024: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. Itaska, IL: AAP; 2024.

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.