Position statement

Sleep matters: Supporting healthy sleep for children and youth with neurodevelopmental disabilities (NDDs)

Posted: Aug 19, 2025

Principal author(s)

Megan Thomas MBChB, PhD, Sarah Shea MD; Canadian Paediatric Society, Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Committee

Abstract

Children with neurodevelopmental disabilities are at high risk for sleep problems, which can negatively affect their health and that of their families. Improving sleep may be one of the most effective ways to improve behaviour, mood, positive social interaction, attention and learning, and reduce future risks for poor metabolic and mental health. While insomnia is the most common concern, increased rates of other sleep disorders are also found in this population. Sleep problems require prompt identification and intervention, which includes recognizing or ruling out contributory medical conditions. Most sleep issues can be addressed through measures that improve sleep habits/hygiene alongside behavioural strategies that respect cultural diversity and parental priorities. If behavioural strategies fail or are only partially successful, melatonin can be used, with medical supervision. Other medication strategies may be needed in difficult cases, but these should be carefully considered and monitored because most have potential for impairing sleep quality or side effects.

Keywords: Autism; Healthy sleep; Melatonin; Neurodevelopmental disorders; Sleep

Background

Sleep is important for maintaining and optimizing physical and mental health, including immune function[1], pain perception[2][3], memory and learning[4], behaviour[5] and mood[6], cardiovascular health, and metabolic functioning[7]. Healthy sleep is not just the absence of a sleep disorder. It is characterized by “subjective satisfaction, appropriate timing, adequate duration, high efficiency, and sustained alertness during waking hours”[8]. Despite its importance, insufficient priority has been given to sleep in public health agendas or clinical education programs[9][10].

A normal sleep cycle consists of four different stages that repeat throughout the night approximately every 60 to 90 minutes. Stage one (N1) is light and brief; N2 makes up much of the night’s sleep; N3 is deep sleep, also called slow wave sleep (SWS); and the final stage is rapid eye movement sleep (REM), where dreaming occurs. The first three stages are also called non-REM (NREM) sleep. After a brief arousal the next sleep cycle begins. The proportion of time spent in each cycle varies according to the period of the night, with more SWS at the beginning of the night, when partial arousals can lead to NREM parasomnias, and more REM sleep occurring toward the end of the night, when nightmares typically occur. The pattern and proportions of the different stages of sleep within cycles is referred to as ‘sleep architecture’, and is affected by activity levels, alcohol and medications, age and development, level of pre-sleep arousal, breathing difficulties, and other factors. Understanding normal sleep helps with understanding how to support healthy sleep.

Children and youth with neurodevelopmental disabilities (NDDs), a term now used to include genetic conditions affecting neurodevelopment and neurodevelopmental disorders as defined by DSM-5[11], have prevalence rates for sleep problems of at least 80%[12]. Sleep problems in children lead to insufficient sleep for family members, with wide-reaching implications for family health and functioning[13]-[15].

The most common sleep problems for children and youth with NDDs fall under the umbrella of behavioural insomnia[16] and include bedtime resistance, prolonged sleep onset latency, waking during the night, and waking too early. These are the same sleep problems seen in typically developing (TD) children and usually respond to the same interventions of optimizing sleep habits (sleep hygiene) and behavioural interventions[16]-[20]. However, in children living with an NDD, such problems occur with greater frequency, are more often of chronic duration, and additional steps and a longer time frame may be required for success[21].

Medical comorbidities have an increased prevalence in children with NDDs. Sleep has a bidirectional relationship with many of these co-morbidities, making intervention that much more important.

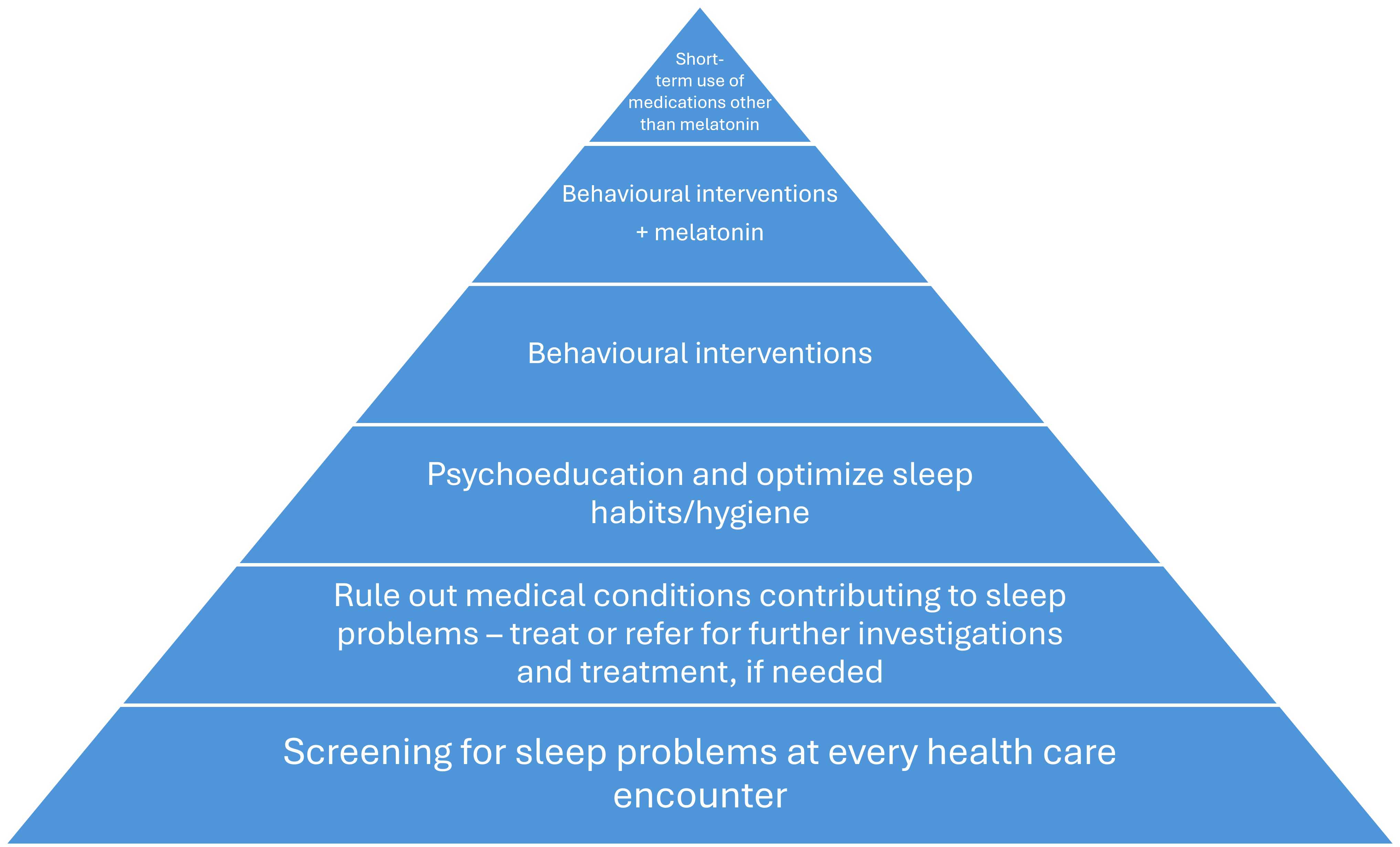

Figure 1. Framework for assessing and managing sleep disorders

Framework for assessing and managing sleep disorders (Figure 1)

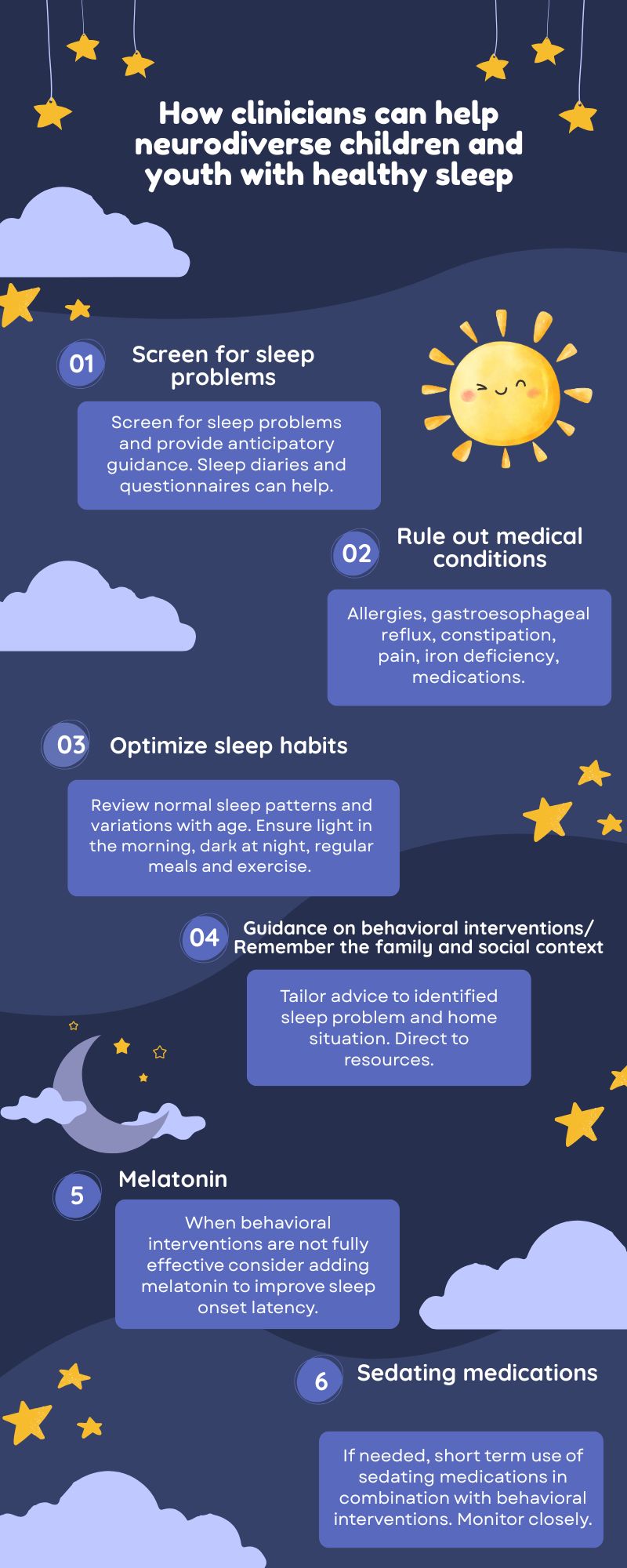

Screen for sleep problems

Sleep surveillance and anticipatory guidance to optimize sleep should be an integral part of health care for all children with NDDs. The use of screening questionnaires such as BEARS (short for Bedtime problems, Excessive daytime sleepiness, Awakenings during the night, Regularity and duration of sleep, Sleep-disordered breathing) for children aged 2 to 12 years[22] and the Adolescent Sleep Hygiene Scale[23] for youth over 12 years old can help.

Rule out medical conditions contributing to sleep problems

While most sleep problems in children with NDDs are behaviourally based, specific sleep disorders are more common in this group[24]. In addition, allergies, gastroesophageal reflux, constipation, dental caries, and other sources of pain are common. While nocturnal seizures are usually identifiable from history, they should be considered due to increased prevalence of epilepsy in this population.

Medications administered to treat medical and neurobehavioural conditions may cause delayed sleep onset, non-restorative sleep, daytime somnolence, and sleep disruption. Examples include attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medications, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), some anticonvulsants, and corticosteroids.

The most useful investigation for the majority of children is a sleep diary (SD), kept for a minimum of 7 days. The next most useful investigation is a ferritin level. While a ferritin level of 24 to 30 ng/mL (depending on the age of the child) may be considered adequate for hemoglobin synthesis, a level of >50 ng/mL is recommended to support sleep, due to iron’s role in neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. Also, higher peripheral ferritin levels are needed to achieve optimal cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) ferritin levels[25][26]. Guidelines for investigations and treatment of iron levels are in development.

Some sleep disorders require sleep studies for diagnosis. Access to such studies is limited in Canada. Increasing the number of sleep disorder specialists and sleep assessment laboratories and improving access to them should be health care priorities.

Psychoeducation and optimizing sleep habits/hygiene

Normal sleep patterns change throughout the lifespan. Sleep is part of a 24-hour circadian rhythm, and optimizing sleep involves promoting positive habits during the day as well as at night. Focusing too much on night-time misses many of the factors that may be interfering with healthy sleep.

There are two main drivers of sleep: sleep pressure, which increases over the period awake, and the circadian rhythm, which is driven by light and regularity of biological processes such as eating, bedtimes, and getting up times.

Sleep occurs in cycles, and it is normal for children to wake partially or even fully several times throughout the night. It is critical that children settle to sleep initially in the way they are going to re-settle to sleep when these normal arousals occur (i.e., in their own bed, on their own, and not while feeding or watching a screen). Difficulty with sleep onset is often caused by reliance on sleep associations such as parental presence. Problematic waking during the night is often caused by the child never having learned to fall asleep independently[27]. Table 1 provides links to a range of useful resources.

| Table 1. Sleep information and resources | |||

|

Target population |

Extra feature |

Origin |

Link |

|

Everyone |

U.S. |

||

|

Everyone |

Day and night |

Canada |

Make Your Whole Day Matter. Move More. Reduce Sedentary Time. Sleep Well. |

|

Everyone |

23 languages |

Australia |

|

|

Children 0 to 3 years |

Paediatric sleep experts |

Multiple |

My Baby’s Sleep Score |

|

Children 3 to 10 years |

Different languages |

Australia |

Sleep relaxation for children: in pictures Better sleep for autistic children 3-8 years: tips |

|

Children with disabilities |

Comprehensive information |

U.K. |

|

|

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) |

U.K. |

||

|

Children with ASD |

Visual timetable Brief summary of strategies |

U.S. |

ATN/AIR-P Strategies to Improve Sleep in Children with Autism |

|

Teenagers |

U.S. |

||

|

Teenagers with ASD |

U.S. |

||

|

Adults with ASD |

U.K. |

||

|

All ages with NDDs |

Sleep disorders and suggested investigations |

U.K. |

Paediatric neurodisability and sleep disorders: clinical pathways and management strategies |

NDDs Neurodevelopmental disabilities

Addressing sleep problems in children with NDDs: The history is key

Studies show that obtaining a sleep history and negotiating a tailored sleep plan can be achieved within a one-hour appointment[28][29]. Follow-up by telephone to provide ongoing reinforcement or minor adjustments has been shown to be effective[28][30].

When sleep problems are present, a detailed history is required to guide intervention.

Sleep history

Collect relevant information in person orally or using questionnaires or both. Start with the time of the evening meal and progress through a typical evening and night to getting up time, naps, and a brief review of the day. The mnemonic ABCs of SLEEPINGTM[31] can be helpful. The mnemonic stands for: 1) Age-appropriate Bedtimes and wake-times with Consistency, 2) Schedules and routines, 3) Location, 4) Exercise and diet, 5) no Electronics in the bedroom or before bed, 6) Positivity, 7) Independence when falling asleep, and 8) Needs of child met during the day, 9) equal Great sleep. The use of any prescribed or over-the-counter medications, supplements, caffeine, cannabis, or alcohol should be noted.

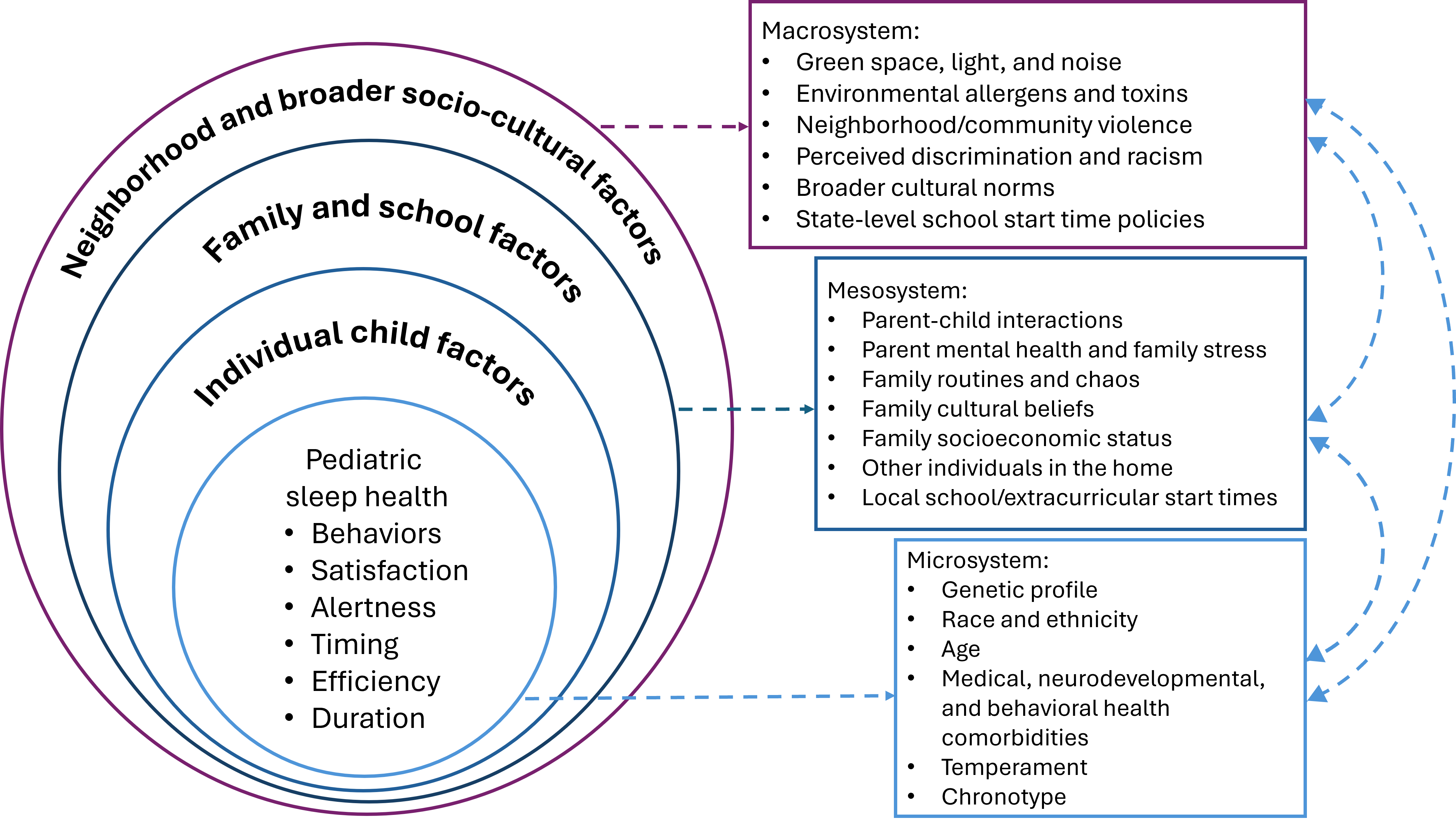

Social and family environmental history

The incidence of sleep problems is markedly higher in families who are experiencing adverse environmental and social circumstances (e.g., suboptimal housing, overcrowding, food insecurity, fear of violence, high noise levels, or complaints from neighbours about the child with NDD or other issues). It is important not to focus solely on the child as the reason for the sleep problems but to also consider their wider context, including whether they have an appropriate bed or sufficient food. It can be more challenging to initiate interventions when other children are sharing the bedroom or concerns about neighbours are a factor. Discussion with parents to establish their priorities, then finding ways to address and support them are vital points of care at this stage. Figure 2 shows key factors contributing to sleep health[32].

Figure 2. Socio-ecological factors hypothesized to contribute to paediatric sleep health domains

Source: Reference 32

Interventions for sleep problems

When sleep problems are of short duration or there are just one or two easily modifiable factors to adjust, providing parents with education about healthy sleep practices may be all that is needed. In one study, 35% of families reported significant improvement after simply receiving an information booklet[33]. While interventions typically involve parents as leading agents of change, children and youth with NDDs should also be involved in establishing priorities and goals whenever possible. When clinicians understand and engage with families regarding the stages of behavioural change[34], and use motivational interviewing[35], the likelihood of success increases.

Behavioural management

Evidence for the effectiveness of behavioural management of sleep problems in typically developing children is well established[36]. More recent evidence of its effectiveness in NDDs has led to guidelines and recommendations which emphasize behavioural management as the first line of intervention after medical reasons have been considered and treated or excluded[17][20][28][37]-[43].

Individualizing such advice will optimize success. While healthy sleep principles are universally applicable, adaptations may be needed for cultural, environmental, and parent or child preferences. For example, while having a completely dark room for sleeping is ideal, some children find it a source of anxiety. Changing lights from blue or white to yellow or red and keeping them as dim as possible are effective compromises. While giving up screen time before bedtime may be rejected, confining screen use to earlier in the evening is a possible strategy. When co-sleeping is a parent’s choice, this must be respected and built into the plan.

Behavioural change can be difficult and takes time. Trying to change multiple routines or conditions simultaneously, or making too large a change all at once, does not allow a child or youth’s physiological, emotional, or cognitive adaptations to develop.

Behavioural insomnia

It can be helpful to divide sleep concerns up by time period (e.g., before bedtime and the bedtime routine; settling to sleep and sleep onset; waking and behaviours during the night; time of waking; and ability to start the day).

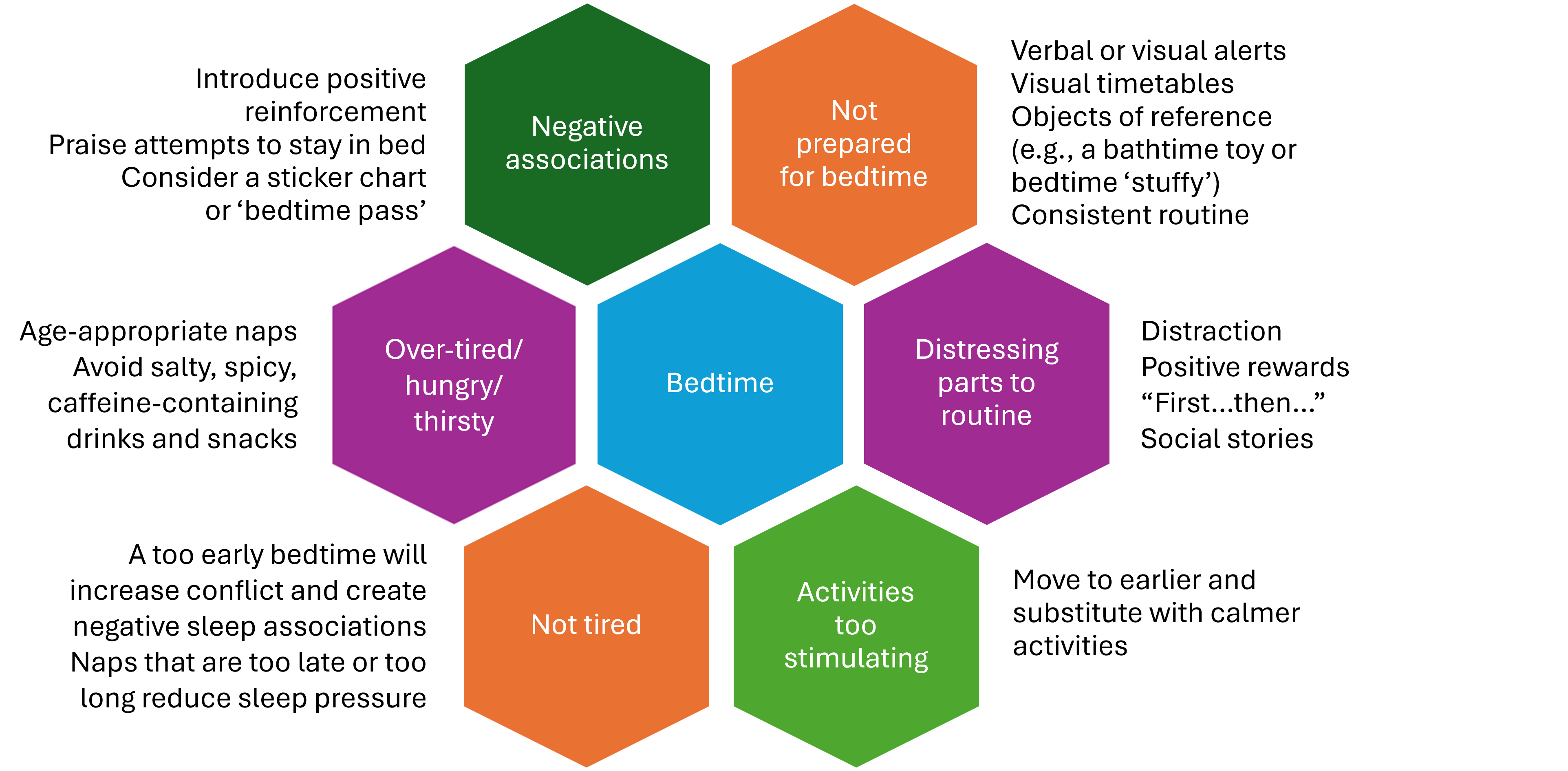

Before bedtime and the bedtime routine

The aim here is to ensure that sleep and bedtime are perceived as part of a positive, calm, and happy process. Explore and address any factors that run counter to this (Figure 3). Supportive resources can be found in Table 1, and strategies described at ATN/AIR-P Strategies to Improve Sleep in Children with Autism are particularly helpful.

Figure 3. Strategies that support a happy, calm bedtime

Waking and behaviours during the night

Problematic night wakings are often due to a child’s never having learned to fall asleep independently. Ensuring this skill is established at the start of the night is fundamental. Other common reasons for waking during the night include external factors such as noise, intrinsic factors such as pain or reflux or constipation, problems with sleep maintenance, and parasomnias. Problems with sleep maintenance may also be caused by inconsistent routines, high levels of pre-sleep arousal, medications, sleep disorders such as sleep disordered breathing, and genetic factors affecting sleep architecture.

Early waking

Check for and remove unrecognized reinforcing factors, such as access to video games. Consider integrating visual signals showing when it is acceptable to get up for the day, such as an annotated or colour changing clock. If a child is getting sufficient sleep but is an early riser, provide rewards for playing quietly in their room without disturbing others.

Parasomnias

Parasomnias are undesirable experiences that occur during sleep. Common NREM parasomnias include night terrors, sleepwalking, and confusional arousals. Advise parents not to wake the child during an episode but, rather, to simply ensure they are safe and, if needed, guide them back to bed. Parasomnias are more frequent with sleep deprivation, and addressing specific reasons for poor sleep is important. Night terrors present as episodes of intense distress, with vocalizations and movements while partially asleep. While these events are usually not remembered by the child, they can be distressing for parents. A night terror typically lasts for several minutes and can continue for 20 to 40 minutes. If night terrors are particularly frequent or troublesome, waking the child 15 to 30 minutes before the time they usually occur each night for at least 2 weeks can be an effective strategy[44]. By contrast, nightmares occur during REM sleep and are vividly recalled. While it is appropriate to provide comfort and reassurance with nightmares, parents should avoid initiating co-sleeping. If a particular nightmare is recurring, guided imagery during the day, that is, talking about the nightmare sequence with the child or youth and then helping to change it into a funny or nonthreatening event, can be helpful.

Pharmacological supports

Medications should not be the first choice or the only sleep intervention for a paediatric sleep problem. However, use of a medication may have a role provided it is combined with nonpharmacological or behavioural management[45]-[47]. Iron levels should be optimized through diet or, if needed, iron medication[48].

Melatonin

Melatonin is readily available in Canada and is being widely used by parents to address children’s sleep problems. Clinicians should understand how melatonin works and be prepared to discuss this option with families.

Melatonin is a hormone produced by the pineal gland in response to dim light, and it plays an important role in the circadian rhythm. Melatonin has a phase-shifting effect when administered at close to physiological doses (0.1 to 0.3 mg, taken a few hours before bedtime). When administered at the supraphysiological doses typically prescribed to promote sleep (1 to 5 mg), melatonin has both sleep-inducing and anxiolytic effects[49]. Melatonin levels increase normally during the evening but are suppressed by light, particularly blue light. Melatonin secretion starts in infants between 3 and 6 months of age, increases to maximal levels in early childhood, then decreases at puberty onset. Inconsistent sleep adversely affects melatonin production, while a regular sleep routine supports normal secretion. Stress and high cortisol levels have the opposite effect to melatonin, prolonging sleep onset and leading to increased sleep fragmentation[50]. Reduced melatonin levels are observed in various diseases and a number of studies have demonstrated physiological abnormalities in children with ASD compared with controls[51].

Melatonin’s action can be considered as helping the recipient enter a behavioural state that is conducive to sleep onset[49]. Therefore, using melatonin adjunctively with behavioural strategies rather than in isolation is important[42]. It is also important not to give an additional dose during the night if a child wakes, due to melatonin’s chronobiotic properties. Slow-release preparations more effectively mimic endogenous melatonin release[52].

A number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs)[33][52]-[57], systematic reviews, and metanalyses of melatonin use in NDDs, particularly ASD, both following or alongside behavioural interventions[17][40][51][58]-[60] have consistently found that melatonin reduces time of sleep onset. The most frequent treatment-related adverse events are fatigue (6.3%), somnolence (6.3%), and mood swings (4.2%)[56].

A challenge for safe melatonin use is the lack of a licensed pharmaceutical-grade product in North America. One Canadian study showed significant variability of melatonin content in natural health products labelled as melatonin and the presence of other substances[61]. A lack of efficacy and the occurrence of side effects from these products may relate to the dose variation or other substances being present. Despite these concerns, caregivers have expressed treatment satisfaction after administering melatonin to their child and report positive impacts on their own quality of life[62][63]. They have also expressed a preference for melatonin use in conjunction with behavioural interventions[62]. The International Paediatric Sleep Association published an expert consensus statement in 2024[40] with recommendations relating to children with autism and other NDDs (Table 2).

| Table 2. Melatonin recommendations | |||||

|

Caution |

Indication |

First address |

Dose |

When to administer |

Contraindicated |

|

Use with medical supervision and re-evaluate periodically |

Delayed sleep onset insomnia if behavioural strategies alone have not been fully effective |

Co-existing medical conditions Concomitant medications Other reasons for delayed sleep onset |

1 to 3 mg Increase gradually if needed to a maximum of 10 mg |

30 to 60 minutes before desired sleep onset |

For children <2 years old without paediatric sleep specialist advice |

Other medications

No licensed medications for insomnia exist for children and adolescents in Canada, appropriate formulations are also lacking, and guidance regarding safety and appropriate treatment doses for different ages is limited. Medications thought to promote sleep are often sedating rather than promoting healthy sleep cycles, and they can also have negative cognitive and physiological effects despite a child’s appearing to sleep for longer. If clinical judgement determines a medication is needed, choice should be guided by the nature of the sleep problem and co-occurring conditions. The possibilities of experiencing an adverse drug interaction[64] or making an obstructive respiratory sleep disorder worse must be considered[45].

Clear goals should be shared and agreed upon with parents, and family and caregiver expectations explored with a view to improving rather than eliminating sleep problems. Criteria for when a medication is to be administered (intermittently as needed or nightly), timing and dose escalation, as well as an exit strategy all need to be made explicit and agreed upon before initiation. Close and frequent monitoring for positive and negative drug effects is required[39][45][46][65]-[69] (Table 3).

| Table 3. Medications with sedating properties used off label | ||||

|

Medication |

Impact(s) on sleep |

Evidence of benefit |

Side effects |

When to consider |

|

Antihistamines |

May reduce sleep onset latency (SOL) |

RCTs have not shown benefit over placebo[65] |

Impaired sleep quality Hangover effects Tolerance rapidly develops Paradoxical excitability |

Short-term use (2 or 3 days) |

|

Benzodiazepines (BZD) and BZD-like medications |

Decreases slow wave sleep (SWS) and rapid eye movement (REM) Increases light sleep |

Limited efficacy found in paediatric trials compared with placebo[66][67] |

Contraindicated for children Daytime behavioural disinhibition Ataxia Anterograde amnesia[46] Daytime sedation Cognitive impairment Rebound insomnia[64] |

For specialist management of specific neurological symptoms or seriously intrusive parasomnias |

|

Clonidine |

Reduces SOL Affects sleep architecture (SWS and REM)[46] |

Weak evidence from one open label study in 19 children[68] |

Dry mouth Daytime sedation Bradycardia, hypotension, Rebound hypertension Confusional arousals Tolerance |

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder Restless leg syndrome |

|

Guanfacine |

Increases waking after sleep onset Reduces SOL |

One RCT stopped early due to side effects and less total sleep time than with placebo[69] |

Daytime sedation |

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder |

|

Doxepin (low dose only, 1 to 6 mg) |

Sleep maintenance |

Retrospective chart reviews |

Daytime sedation |

Short-term use for night wakings (2 to 4 weeks) |

|

Trazodone (low dose only, 25 to 50 mg) |

Reduces SOL Increases SWS Decreases REM |

No studies in children. In adults, no improvement over baseline with long-term use |

Dizziness, drowsiness, fatigue Central nervous system overstimulation Tolerance Rebound insomnia |

Short-term use (1 month) with clear exit strategy[45] Conjunctively with management of mood disorders |

|

Atypical antipsychotics (risperidone, quetiapine, aripiprazole, olanzapine) |

Increases sleep continuity Suppresses REM Increases motor restlessness |

No studies for insomnia in children |

Considerable metabolic side effects, which can contribute to further sleep issues such as sleep-disordered breathing[64] Daytime sedation |

Use only when a co-morbid condition is present (e.g., aggression or self-injurious behaviour) |

|

Gabapentin |

May increase sleep continuity |

Retrospective chart review |

Daytime sedation Agitation and difficulty falling asleep |

Restless leg syndrome Use as part of management of dystonia or neuropathic pain |

RTC Randomized controlled trial

Alternative treatments

There is limited evidence for the effectiveness of alternative treatments such as acupuncture, essential fatty acids, or weighted blankets[58]. The use of background sound (white or pink noise) may be helpful, but there has been little study of its effectiveness. Care should be taken that location of the device and noise levels are safe[70]. Parents should recognize that background noise or music may become a sleep association and night awakenings can worsen if these aids do not continue throughout the night.

Recommendations

- Promote healthy sleep through surveillance and consider a sleep disorder as a contributing factor in children with a physical, mental, learning, or behavioural concern.

- Recognize that sleep-promoting behavioural interventions may need to be broken down into smaller steps with longer time frames for improvement in individuals with neurodevelopmental disabilities.

- Appreciate that sleep and sedation are not equivalent, and many medications prescribed for sleep interfere with normal sleep architecture and do not promote healthy, restorative sleep.

- Advocate for better access to specialized sleep services for diagnosis and treatment of complex sleep disorders.

- Advocate for pharmaceutical-grade melatonin to be made available in Canada.

Acknowledgements

This statement was reviewed by the Community Paediatrics Committee and the Developmental Paediatrics Section Executive of the Canadian Paediatric Society, and by representatives of the Canadian Sleep Society (CSS).

CANADIAN PAEDIATRIC SOCIETY MENTAL HEALTH AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES COMMITTEE (2024-2025)

Members: Scott McLeod MD (Chair), Amy Ornstein MD (Board Representative), Natasha Saunders MD, Megan Thomas PhD, MBChB, Ripudaman Minhas MD, Lester Liao MD, Man Ying Bernice Ho BSc (Resident Member)

Liaisons: Olivia MacLeod MD (Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry), Angela Orsino MD (CPS Developmental Paediatrics Section), Leigh Wincott MD (CPS Mental Health Section)

Principal authors: Megan Thomas MBChB, PhD, Sarah Shea MD

Funding

There is no funding to declare.

Potential Conflict of Interest

Dr. Megan Thomas reported being on the Board of Directors of the Nova Scotia Early Childhood Development Intervention Services. No other disclosures were reported.

References

- Bryant PA, Trinder J, Curtis N. Sick and tired: Does sleep have a vital role in the immune system? Nat Rev Immunol 2004;4(6):457-67. doi: 10.1038/nri1369

- Finan PH, Goodin BR, Smith MT. The association of sleep and pain: An update and a path forward. J Pain 2013;14(12):1539-52. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.08.007

- Lautenbacher S, Kundermann B, Krieg JC. Sleep deprivation and pain perception. Sleep Med Rev 2006;10(5):357-69. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2005.08.001

- Hill CM, Hogan AM, Karmiloff-Smith A. To sleep, perchance to enrich learning? Arch Dis Child 2007;92(7):637-43. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.096156

- Beebe DW. Cognitive, behavioral, and functional consequences of inadequate sleep in children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am 2011;58(3):649-65. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.03.002

- Triantafillou S, Saeb S, Lattie EG, Mohr DC, Kording KP. Relationship between sleep quality and mood: Ecological momentary assessment study. JMIR Ment Health 2019;6(3):e12613. doi: 10.2196/12613

- Quist JS, Sjödin A, Chaput JP, Hjorth MF. Sleep and cardiometabolic risk in children and adolescents. Sleep Med Rev 2016;29:76-100. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.09.001

- Buysse DJ. Sleep health: Can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep 2014;37(1):9-17. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3298

- Lim DC, Najafi A, Afifi L, et al. The need to promote sleep health in public health agendas across the globe. Lancet Public Health 2023;8(10):e820-e6. doi: 10.1016/s2468-2667(23)00182-2

- Ramar K, Malhotra RK, Carden KA, et al. Sleep is essential to health: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement. J Clin Sleep Med 2021;17(10):2115-9. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9476

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR). 5th edn. Washington, DC: APA; 2013.

- Didden R, Sigafoos J. A review of the nature and treatment of sleep disorders in individuals with developmental disabilities. Res Dev Disabil 2001;22(4):255-72. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(01)00071-3

- Chu J, Richdale AL. Sleep quality and psychological wellbeing in mothers of children with developmental disabilities. Res Dev Disabil 2009;30(6):1512-22. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2009.07.007

- Martin CA, Papadopoulos N, Chellew T, Rinehart NJ, Sciberras E. Associations between parenting stress, parent mental health and child sleep problems for children with ADHD and ASD: Systematic review. Res Dev Disabil 2019;93:103463. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2019.103463

- Esbensen AJ, Schworer EK, Hoffman EK, Wiley S. Child sleep linked to child and family functioning in children with Down syndrome. Brain Sci 2021;11(9):1170. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11091170

- Corkum P, Davidson FD, Tan-MacNeill K, Weiss SK. Sleep in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: A focus on insomnia in children with ADHD and ASD. Sleep Med Clin 2014;9(2):149-68. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2014.02.006

- Cuomo BM, Vaz S, Lee EAL, Thompson C, Rogerson JM, Falkmer T. Effectiveness of sleep-based interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-synthesis. Pharmacotherapy 2017;37(5):555-78. doi: 10.1002/phar.1920

- Scantlebury A, McDaid C, Dawson V, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for non-respiratory sleep disturbance in children with neurodisabilities: A systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol 2018;60(11):1076-92. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13972

- Zhou ES, Owens J. Behavioral treatments for pediatric insomnia. Curr Sleep Med Rep 2016;2(3):127-35. doi: 10.1007/s40675-016-0053-0

- Rigney G, Ali NS, Corkum PV, et al. A systematic review to explore the feasibility of a behavioural sleep intervention for insomnia in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: A transdiagnostic approach. Sleep Med Rev 2018;41:244-54. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.03.008

- Meltzer LJ, Wainer A, Engstrom E, Pepa L, Mindell JA. Seeing the whole elephant: A scoping review of behavioral treatments for pediatric insomnia. Sleep Med Rev 2021;56:101410. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101410

- Owens JA, Dalzell V. Use of the ‘BEARS’ sleep screening tool in a pediatric residents' continuity clinic: A pilot study. Sleep Med 2005;6(1):63-9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.07.015

- Storfer-Isser A, Lebourgeois MK, Harsh J, Tompsett CJ, Redline S. Psychometric properties of the Adolescent Sleep Hygiene Scale. J Sleep Res 2013;22(6):707-16. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12059

- McDonald A, Joseph D. Paediatric neurodisability and sleep disorders: Clinical pathways and management strategies. BMJ Paediatr Open 2019;3(1):e000290. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2018-000290

- Cameli N, Beatrice A, Colacino Cinnante EM, et al. Restless sleep disorder and the role of iron in other sleep-related movement disorders and ADHD. Clin Transl Neurosci 2023;7(3):18. doi: 10.3390/ctn7030018

- Dosman C, Witmans M, Zwaigenbaum L. Iron’s role in paediatric restless legs syndrome – a review. Paediatr Child Health 2012;17(4):193-7. doi: 10.1093/pch/17.4.193

- Cook G, Carter B, Wiggs L, Southam S. Parental sleep-related practices and sleep in children aged 1-3 years: A systematic review. J Sleep Res 2024;33(4):e14120. doi: 10.1111/jsr.14120

- Pattison E, Papadopoulos N, Marks D, McGillivray J, Rinehart N. Behavioural treatments for sleep problems in children with autism spectrum disorder: A review of the recent literature. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2020;22(9):46. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01172-1

- Papadopoulos N, Sciberras E, Hiscock H, et al. Sleeping sound autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A randomised controlled trial of a brief behavioural sleep intervention in primary school-aged autistic children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2022;63(11):1423-33. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13590

- Stuttard L, Clarke S, Thomas M, Beresford B. Replacing home visits with telephone calls to support parents implementing a sleep management intervention: Findings from a pilot study and implications for future research. Child Care Health Dev 2015;41(6):1074-81. doi: 10.1111/cch.12250

- Allen SL, Howlett MD, Coulombe JA, Corkum PV. ABCs of SLEEPING: A review of the evidence behind pediatric sleep practice recommendations. Sleep Med Rev 2016;29:1-14. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.08.006

- Meltzer LJ, Williamson AA, Mindell JA. Pediatric sleep health: It matters, and so does how we define it. Sleep Med Rev 2021;57:101425. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101425

- Gringras P, Gamble C, Jones AP, et al. Melatonin for sleep problems in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: Randomised double masked placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2012;345:e6664. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6664

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 1997;12(1):38-48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38

- Bischof G, Bischof A, Rumpf HJ. Motivational interviewing: An evidence-based approach for use in medical practice. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2021;118(7):109-15. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0014

- Morgenthaler TI, Owens J, Alessi C, et al. Practice parameters for behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep 2006;29(10):1277-81.

- Galion AW, Farmer JG, Connolly HV, et al. A practice pathway for the treatment of night wakings in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2024;54(8):2926-45. doi: 10.1007/s10803-023-06026-2

- Gruber R, Carrey N, Weiss SK, et al. Position statement on pediatric sleep for psychiatrists. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014;23(3):174-95.

- Williams Buckley A, Hirtz D, Oskoui M, et al. Practice guideline: Treatment for insomnia and disrupted sleep behavior in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2020;94(9):392-404. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000009033

- Kotagal S, Malow B, Spruyt K, et al. Melatonin use in managing insomnia in children with autism and other neurogenetic disorders – An assessment by the International Pediatric Sleep Association (IPSA). Sleep Med 2024;119:222-8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2024.04.008

- Rosen CL, Aurora RN, Kapur VK, et al. Supporting American Academy of Neurology’s new clinical practice guideline on evaluation and management of insomnia in children with autism. J Clin Sleep Med 2020;16(6):989-90. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8426

- Malow BA, Byars K, Johnson K, et al. A practice pathway for the identification, evaluation, and management of insomnia in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2012;130 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S106-24. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0900I

- Keogh S, Bridle C, Siriwardena NA, et al. Effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for insomnia in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2019;14(8):e0221428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221428

- Mason TBA, Pack AI. Pediatric parasomnias. Sleep 2007;30(2):141-51. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.2.141

- Ekambaram V, Owens J. Medications used for pediatric insomnia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2024;47(1):87-101. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2023.06.006

- Gringras P. When to use drugs to help sleep. Arch Dis Child 2008;93(11):976-81. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.128728

- Wilson S, Anderson K, Baldwin D, et al. British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus statement on evidence-based treatment of insomnia, parasomnias and circadian rhythm disorders: An update. J Psychopharmacol 2019;33(8):923-47. doi: 10.1177/0269881119855343

- Leung W, Singh I, McWilliams S, Stockler S, Ipsiroglu OS. Iron deficiency and sleep – A scoping review. Sleep Med Rev 2020;51:101274. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101274

- Cruz-Sanabria F, Carmassi C, Bruno S, et al. Melatonin as a chronobiotic with sleep-promoting properties. Curr Neuropharmacol 2023;21(4):951-87. doi: 10.2174/1570159x20666220217152617

- Hirotsu C, Tufik S, Andersen ML. Interactions between sleep, stress, and metabolism: From physiological to pathological conditions. Sleep Sci 2015;8(3):143-52. doi: 10.1016/j.slsci.2015.09.002

- Rossignol DA, Frye RE. Melatonin in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol 2011;53(9):783-92. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.03980.x

- Gringras P, Nir T, Breddy J, Frydman-Marom A, Findling RL. Efficacy and safety of pediatric prolonged-release melatonin for insomnia in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017;56(11):948-57.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.09.414

- Appleton RE, Jones AP, Gamble C, et al. The use of melatonin in children with neurodevelopmental disorders and impaired sleep: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel study (MENDS). Health Technol Assess 2012;16(40):i-239. doi: 10.3310/hta16400

- Maras A, Schroder CM, Malow BA, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of pediatric prolonged-release melatonin for insomnia in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2018;28(10):699-710. doi: 10.1089/cap.2018.0020

- Cortesi F, Giannotti F, Sebastiani T, Panunzi S, Valente D. Controlled-release melatonin, singly and combined with cognitive behavioural therapy, for persistent insomnia in children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Sleep Res 2012;21(6):700-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2012.01021.x

- Malow BA, Findling RL, Schroder CM, et al. Sleep, growth, and puberty after 2 years of prolonged-release melatonin in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2021;60(2):252-61.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.12.007

- Hayashi M, Mishima K, Fukumizu M, et al. Melatonin treatment and adequate sleep hygiene interventions in children with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J Autism Dev Disord 2022;52(6):2784-93. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-05139-w

- Beresford B, McDaid C, Parker A, et al. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for non-respiratory sleep disturbance in children with neurodisabilities: A systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2018;22(60):1-296. doi: 10.3310/hta22600

- Parker A, Beresford B, Dawson V, et al. Oral melatonin for non-respiratory sleep disturbance in children with neurodisabilities: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Dev Med Child Neurol 2019;61(8):880-90. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14157

- Abdelgadir IS, Gordon MA, Akobeng AK. Melatonin for the management of sleep problems in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child 2018;103(12):1155-62. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314181

- Erland LA, Saxena PK. Melatonin natural health products and supplements: Presence of serotonin and significant variability of melatonin content. J Clin Sleep Med 2017;13(2):275-81. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6462

- Lee SKM, Smith L, Tan ECK, Cairns R, Grunstein R, Cheung JMY. Melatonin use in children and adolescents: A scoping review of caregiver perspectives. Sleep Med Rev 2023;70:101808. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2023.101808

- Schroder CM, Malow BA, Maras A, et al. Pediatric prolonged-release melatonin for sleep in children with autism spectrum disorder: Impact on child behavior and caregiver’s quality of life. J Autism Dev Disord 2019;49(8):3218-20. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04046-5

- Bruni O, Angriman M, Melegari MG, Ferri R. Pharmacotherapeutic management of sleep disorders in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2019;20(18):2257-71. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2019.1674283

- Merenstein D, Diener-West M, Halbower AC, Krist A, Rubin HR. The trial of infant response to diphenhydramine: The TIRED study – A randomized, controlled, patient-oriented trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006;160(7):707-12. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.707

- Blumer JL, Findling RL, Shih WJ, Soubrane C, Reed MD. Controlled clinical trial of zolpidem for the treatment of insomnia associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children 6 to 17 years of age. Pediatrics 2009;123(5):e770-6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2945

- Sangal RB, Blumer JL, Lankford DA, Grinnell TA, Huang H. Eszopiclone for insomnia associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 2014;134(4):e1095-103. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-4221

- Ming X, Gordon E, Kang N, Wagner GC. Use of clonidine in children with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Dev 2008;30(7):454-60. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2007.12.007

- Rugino TA. Effect on primary sleep disorders when children with ADHD are administered guanfacine extended release. J Atten Disord 2018;22(1):14-24. doi: 10.1177/1087054714554932

- Hugh SC, Wolter NE, Propst EJ, Gordon KA, Cushing SL, Papsin BC. Infant sleep machines and hazardous sound pressure levels. Pediatrics 2014;133(4):677-81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3617

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.