Practice point

Kawasaki disease: Practical guidance on diagnosis and management

Posted: Feb 2, 2026

Principal author(s)

Audrea Chen MD, Evelyn Rozenblyum MD, Nagib Dahdah MD, Bianca Lang MD, Rosie Scuccimarri MD, Piya Lahiry MSc PhD MD, Herman Tam MD, Mercedes Chan MD, Andrea Human MD, Jennifer Lee MD MSc, Peter Wong MD, Paul Tsoukas MD, Rae SM Yeung MD; Canadian Paediatric Society, Community Paediatrics Committee

Abstract

Kawasaki disease (KD) is a systemic vasculitis that requires prompt treatment to prevent coronary artery aneurysms and subsequent cardiac complications. This practice point presents guidance on the diagnosis and management of KD, including scenarios with severe disease and high risk for developing coronary artery aneurysms where subspecialty consultation is important.

Keywords: Antiplatelet; Coronary artery aneurysm; Echocardiography; IVIG; Kawasaki disease

Introduction

Kawasaki disease (KD) is a systemic vasculitis of small- and medium-sized arteries[1][2]. Incidence within Canada is highest in preschoolers (19.6 to 26.0 per 100,000 under the age of 5) but can occur throughout childhood[3]-[5].

KD is a leading cause of acquired childhood heart disease[1]-[5]. Coronary artery lesions, including dilatations and aneurysms, are the most significant sequelae (20% to 25% of untreated patients)[6]. Coronary artery complications from aneurysms are rare (<1%), but include thrombosis, myocardial ischemia, and rupture[1][6][7].

Diagnosis

Clinical criteria (Table 1) establish the diagnosis although some criteria may only be elicited on history. Incomplete KD should be considered when fever and <4 principal criteria are present, or in infants (<12 months old) with prolonged, unexplained fever[1]. Other diagnoses should also be considered (Table 2). KD may occur concurrently with infection, and both should be treated[8]. If KD presents with shock, sepsis should be considered.

|

Table 1. Clinical features of Kawasaki disease (KD) |

|

|

Complete KD |

Fever of ≥5 days* and at least 4 of the following:

*When ≥4 principal clinical criteria are present, diagnosis can be made at 4 days of fever |

|

Incomplete KD Criteria[1] |

AND Either ESR ≥40 mm/h OR CRP ≥30 mg/L If the above criteria are met, they must either have:

OR 3/6 of the following:

|

|

Desquamating perineal rash, gallbladder hydrops, aseptic meningitis, inflammation at previous BCG vaccination site, uveitis, retropharyngeal edema, arthritis |

|

ALT Alanine aminotransferase; BCG Bacillus Calmette-Guérin; CRP C-reactive protein; ESR Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; WBC White blood cells

Shock scenarios

|

Information drawn from reference 8

Echocardiography

Coronary artery echocardiography is essential to KD management, but diagnosis and therapy should not be delayed awaiting echocardiography[1][2].

Coronary artery diameter interpretation is based on Z-score calculations[9]. Coronary artery lesion categories include dilatation (Z ≥2 to <2.5), small (Z ≥2.5 to <5), medium (Z ≥5 to <10), and large or giant aneurysms (Z ≥10, or diameter ≥8 mm)[10]. Cardiac prognosis worsens with increasing coronary artery size[10]. Coronary arteries should be monitored with serial echocardiograms because aneurysms may develop up to 4 to 6 weeks after disease onset[1][2].

IV immunoglobulin (IVIG)

One dose of IVIG (2 g/kg) reduces the risk of coronary artery aneurysms to <5% when provided within the first 10 days of fever[1]. If KD is suspected, patients should still be treated after day 10 when fever and inflammation persist[1]. Fever should resolve by 24 to 36 hours post-IVIG completion. IVIG can cause erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) elevation that does not reflect persistent inflammation[1].

IVIG side effects include infusion reactions, fever, headaches, aseptic meningitis, and autoimmune hemolytic anemia[11]. Hemolytic anemia may relate to blood group antibodies administered via IVIG, which in cases of treatment escalation may determine whether a second dose of IVIG or alternative agent is required[11].

Antiplatelet/Anticoagulation

Patients who are not at risk of bleeding (platelet count >80 x 109/L) should start acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) during the febrile illness to prevent coronary artery thrombus formation[1][2]. Two approaches are equally acceptable based on evidence: initiating a moderate (anti-inflammatory) dose of ASA (30 to 50 mg/kg/day divided every 6 hours) followed by a lower dose (3 to 5 mg/kg once daily) after the patient is afebrile[12][13], or administering low-dose ASA from the outset[14].

If ASA is contraindicated, as for patients with influenza or varicella, dipyridamole and clopidogrel are alternative agents[1]. Avoid use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) concurrently with ASA because they can interfere with ASA’s antiplatelet (anticoagulant) effect[1].

Depending on the degree of coronary artery involvement, administering dual antiplatelet agents and/or anticoagulation may be indicated[15]. Anticoagulation is mandatory for large and giant aneurysms[1]. Subspecialist consultation is recommended.

Corticosteroids

Evidence regarding the role of corticosteroids in improving coronary outcomes is conflicting[2][15][16]. High-dose corticosteroids (prednisone 2 mg/kg/day to a maximum of 60 mg) are sometimes used in consultation with rheumatology, for up-front intensification or second-line therapy for IVIG resistance.

Methylprednisolone IV pulse doses of 30 mg/kg (to a maximum of 1000 mg/dose) are typically reserved for KD shock syndrome (KDSS) or macrophage activation syndrome (MAS).

High-risk clinical scenarios in KD

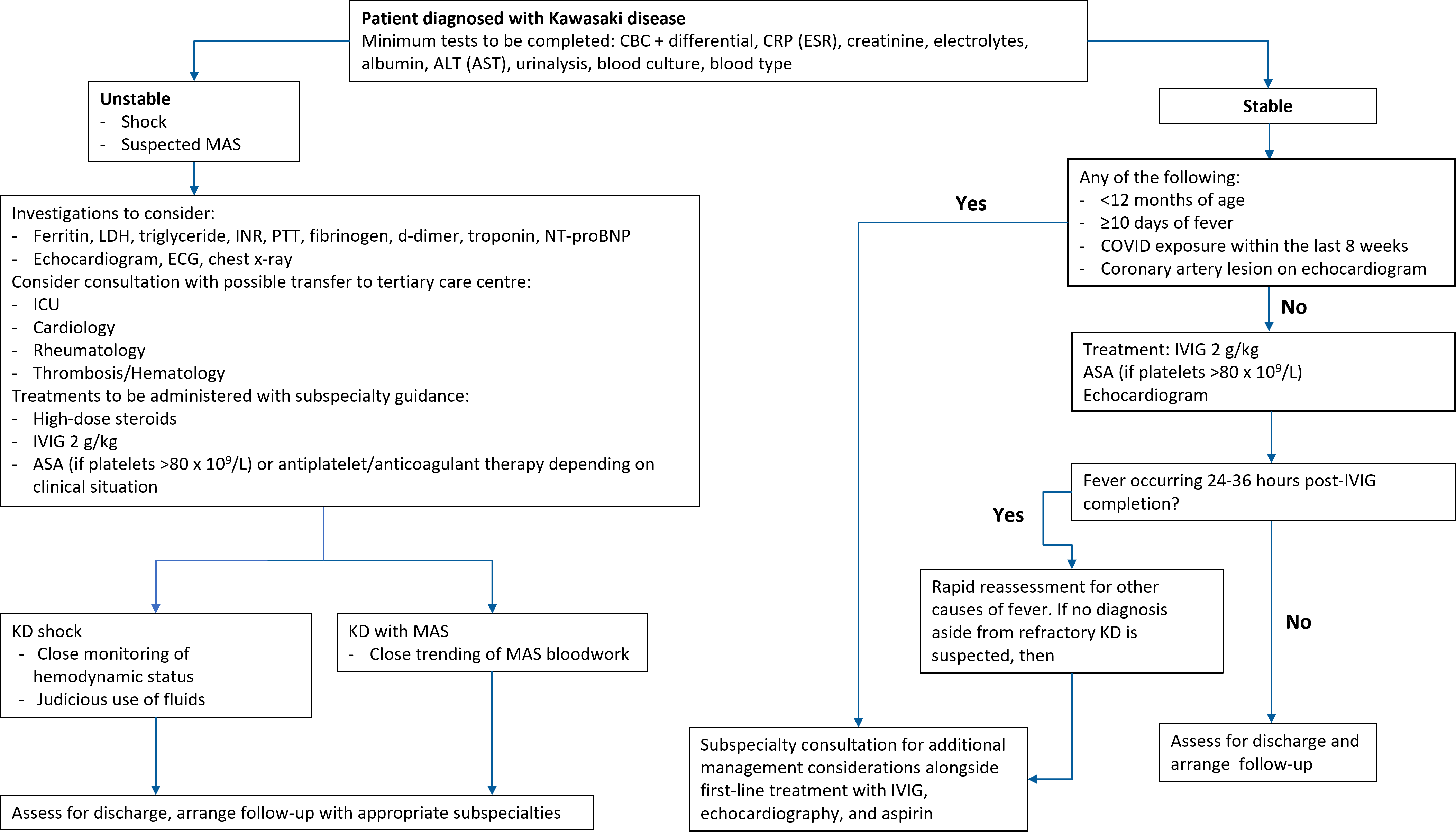

An algorithm highlighting the following scenarios is presented in Figure 1.

Macrophage activation syndrome

MAS is a potentially fatal hyperinflammatory condition occurring in 2% to 5% of KD cases[17]. MAS should be considered when a child is unstable, unresponsive to IVIG, or has cytopenias. Other signs of MAS include hepatosplenomegaly, encephalopathy, and multi-organ failure. Blood work may show hyperferritinemia, hypofibrinogenemia, transaminitis, coagulopathy, and dropping ESR with rising CRP[17]. Prompt initiation of immunomodulatory treatment (e.g., corticosteroids, anakinra) can reduce morbidity and mortality substantially.

KD shock syndrome (KDSS)

KDSS is defined as having KD features, ≥20% decrease in systolic blood pressure (from normal for age and sex), and/or clinical signs of poor peripheral perfusion[2][18]. KDSS is rare (2.6 to 6.9% of KD cases), though it is likely under-recognized and often misdiagnosed[19]. Early identification and close monitoring are important because hypotension or persistent tachycardia (or both) can signal KDSS[20]. Judicious use of fluids is recommended, and inotropic or respiratory support may be required. An initial high dose of methylprednisolone may be effective in temporizing KDSS[21].

Coronary artery lesions on echocardiogram at diagnosis

Coronary arterial lesions at diagnosis are associated with increased risk for IVIG-refractory disease which, in turn, is thought to lead to increasing coronary arterial size[22]. Additional immunosuppression to treat persistent inflammation may be required. A normal echocardiogram at presentation does not exclude KD or risk for developing coronary arterial lesions following treatment[1][2].

IVIG resistance

Approximately 10% to 20% of patients with KD have IVIG resistance (persistent or recurrent fever at least 24 to 36 hours post-IVIG completion)[23][24]. These patients are at higher risk for coronary artery aneurysms and require additional treatment[23]. Other causes of fever should also be considered. Treatment for IVIG resistance varies[25]. A second dose of IVIG is the most used second-line treatment[25]. When a significant drop in hemoglobin (>20 g/L) occurs after the first dose of IVIG, an alternative second-line treatment should be considered for treatment of IVIG resistance (i.e., corticosteroids, infliximab, anakinra)[2][26][27].

Additional high-risk characteristics

Close monitoring or treatment intensification (or both) should be considered on a case-by-case basis for infants younger than 12 months old because they, along with children with prolonged fever (≥10 days), are at highest risk for developing aneurysms[28][29].

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is a hyperinflammatory syndrome suspected with COVID-19 exposure or infection in the preceding 2 to 8 weeks and fever accompanied by KD features, gastrointestinal/neurological/cardiac symptoms, or shock[30]-[32]. Rates of MIS-C have decreased significantly since the early pandemic[33]. Vaccination against COVID-19 remains important for protecting against MIS-C[33]. For more information, see this CPS MIS-C statement[32].

Discharge and follow-up

At minimum, patients should be afebrile for 24 to 48 hours post-IVIG completion and have follow-up echocardiography and access to primary care/paediatrics for guidance in the event of recurrent symptoms (Table 3). Monitoring CBC and CRP 1 to 2 weeks after discharge may help identify persistent inflammation or hemolytic anemia.

Patients with normal coronary arteries typically do not require follow-up beyond 6 to 8 weeks[1]. When small to moderate aneurysms are present, they usually regress within one year[22]. About 1.5% to 3% of patients have recurrent KD within the first year (fever and clinical criteria ≥2 months after the first episode)[1].

|

Table 3. Discharge instructions |

|

ASA Acetylsalicylic acid; IVIG Intravenous immunoglobulin

Recommendations

- Consider a diagnosis of Kawasaki disease (KD) for a patient with fever and <4 principal features, especially for infants.

- Consultation with subspecialists is recommended when patients are at high risk for developing coronary arterial lesions or complications of KD.

- First-line therapy includes one 2 g/kg dose of intravenous immunoglobulin is followed by a daily antiplatelet agent that is continued until follow-up echocardiograms are completed.

Figure 1. Algorithm outlining KD assessment and management. (Optional investigations are in brackets.)

ALT Alanine transaminase; ASA Acetylsalicylic acid; AST Aspartate transaminase; CBC Complete blood count; COVID Coronavirus disease-19; CRP C-reactive protein; ECG Electrocardiogram; ESR Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; ICU Intensive care unit; INR International normalized ratio; IVIG Intravenous immunoglobulin; KD Kawasaki disease; LDH Lactate dehydrogenase; MAS Macrophage activation syndrome; NT-proBNP N-terminus pro beta natriuretic peptide; PTT Partial thromboplastin time

Acknowledgement

This practice point has been reviewed by the Hospital Paediatrics Section Executive and the Acute Care and Community Paediatrics Committees of the Canadian Paediatric Society.

CANADIAN PAEDIATRIC SOCIETY COMMUNITY PAEDIATRICS COMMITTEE (2024-2025)

Members: Peter Wong MD (Chair), Jill Borland Starkes MD (Board Representative), Michael Hill MD, Audrey Lafontaine MD, Meta van den Heuvel MD, Kelcie Lahey MD MSc

Liaisons: Richa Agnihotri MD (CPS Community Paediatrics Section)

Principal authors: Audrea Chen MD, Evelyn Rozenblyum MD, Nagib Dahdah MD, Bianca Lang MD, Rosie Scuccimarri MD, Piya Lahiry MSc PhD MD, Herman Tam MD, Mercedes Chan MD, Andrea Human MD, Jennifer Lee MD MSc, Peter Wong MD, Paul Tsoukas MD, Rae SM Yeung MD

Funding

There is no funding to declare.

Potential Conflict of Interest

Dr. Rae Yeung reported receiving funding from CIHR, Genome Canada, CFI, PHAC, CITF, EU Rare Diseases, Cure JM, KD Canada (peer-reviewed funding), and is a member on the Medical Advisory Board of Kawasaki Disease Canada. Dr. Rosie Scuccimarri was co-chair of the Canadian Rheumatology Association Therapeutics Committee and received an honorarium. She was a member of the Novartis Advisory Board and has received funding from BMS for a patient drug registry. Dr. Mercedes Chan reported receiving financial payments from Novartis as a consultant. Dr. Herman Tam reported receiving financial payments from the Canadian Rheumatology Association as honoraria for developing education content and modules.

No other disclosures were reported.

References

- McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: A scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;135(17):e927–99. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484

- Jone P, Tremoulet A, Choueiter N, et al. Update on diagnosis and management of Kawasaki disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024;150(23):e481-e500. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001295

- Manlhiot C, O’Shea S, Chahal N, Yeung RS, McCrindle BW. Incidence of Kawasaki disease in Canada. Can J Cardiol 2014;30(10):S344. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.07.626

- Robinson C, Chanchlani R, Gayowsky A, et al. Incidence and short-term outcomes of Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Res 2021;90(3):670–7. doi: 10.1038/s41390-021-01496-5

- Alkanhal A, Saunders J, Altammar F, et al. Unexpectedly high incidence of Kawasaki disease in a Canadian Atlantic province—an 11-year retrospective descriptive study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2023;21(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s12969-023-00805-y

- Kato H, Ichinose E, Kawasaki T. Myocardial infarction in Kawasaki disease: Clinical analyses in 195 cases. J Pediatr 1986;108(6):923–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80928-3

- Tsuda E, Hirata T, Matsuo O, Abe T, Sugiyama H, Yamada O. The 30-year outcome for patients after myocardial infarction due to coronary artery lesions caused by Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Cardiol 2011;32(2):176–82. doi: 10.1007/s00246-010-9838-y

- Morishita KA, Goldman RD. Kawasaki disease recognition and treatment. Can Fam Physician 2020;66(8):577–9.

- Dallaire F, Dahdah N. New equations and a critical appraisal of coronary artery Z scores in healthy children. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2011;24(1):60-74. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.10.004

- Brown LM, Duffy CE, Mitchell C, Young L. A practical guide to pediatric coronary artery imaging with echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015;28(4):379–91. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2015.01.008

- Berard R, Whittemore B, Scuccimarri R. Hemolytic anemia following intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in patients treated for Kawasaki disease: A report of 4 cases. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2012;10(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-10-10

- Sakulchit T, Benseler SM, Goldman RD. Acetylsalicylic acid for children with Kawasaki disease. Can Fam Physician 2017;63(8):607–9.

- Ito Y, Matsui T, Abe K, et al. Aspirin dose and treatment outcomes in Kawasaki disease: A historical control study in Japan. Front Pediatr 2020;8:249. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00249

- Dallaire F, Fortier-Morissette Z, Blais S, et al. Aspirin dose and prevention of coronary abnormalities in Kawasaki disease. Pediatrics 2017;139(6):e20170098. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0098

- Newburger JW. Kawasaki disease: Medical therapies. Congenit Heart Dis 2017;12(5):641–3. doi: 10.1111/chd.12502

- Green J, Wardle AJ, Tulloh RM. Corticosteroids for the treatment of Kawasaki disease in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2022;5(5):CD011188. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011188.pub3

- Latino GA, Manlhiot C, Yeung RSM, Chahal N, McCrindle BW. Macrophage activation syndrome in the acute phase of Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2010;32(7):527–31. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181dccbf4

- Kanegaye JT, Wilder MS, Molkara D, et al. Recognition of a Kawasaki disease shock syndrome. Pediatrics 2009;123(5):e783-9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1871

- Li Y, Zheng Q, Zou L, et al. Kawasaki disease shock syndrome: Clinical characteristics and possible use of IL-6, IL-10 and IFN-γ as biomarkers for early recognition. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2019;17(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12969-018-0303-4

- Dionne A, Dahdah N. Myocarditis and Kawasaki disease. Int J Rheum Dis 2018;21(1):45–9. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13219

- Campbell AJ, Burns JC. Adjunctive therapies for Kawasaki disease. J Infect 2016;72 Suppl:S1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.04.015

- Liu J, Yue Q, Qin S, Su D, Ye B, Pang Y. Risk factors and coronary artery outcomes of coronary artery aneurysms differing in size and emergence time in children with Kawasaki disease. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022;9:969495. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.969495

- Tremoulet AH, Best BM, Song S, et al. Resistance to intravenous immunoglobulin in children with Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr 2008;153(1):117–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.12.021

- Burns JC, Capparelli EV, Brown JA, Newburger JW, Glode MP. Intravenous gamma-globulin treatment and retreatment in Kawasaki disease. US/Canadian Kawasaki Syndrome Study Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1998;17(12):1144–8. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199812000-00009

- Chan H, Chi H, You H, et al. Indirect-comparison meta-analysis of treatment options for patients with refractory Kawasaki disease. BMC Pediatr 2019;19(1):158. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1504-9

- Gorelik M, Lee Y, Abe M, et al. IL-1 receptor antagonist, anakinra, prevents myocardial dysfunction in a mouse model of Kawasaki disease vasculitis and myocarditis. Clin Exp Immunol 2019;198(1):101–10. doi: 10.1111/cei.13314

- Burns JC, Roberts SC, Tremoulet AH, et al. Infliximab versus second intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of resistant Kawasaki disease in the USA (KIDCARE): A randomised, multicentre comparative effectiveness trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2021;5(12):852–61. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00270-4

- Takekoshi N, Kitano N, Takeuchi T, et al. Analysis of age, sex, lack of response to intravenous immunoglobulin, and development of coronary artery abnormalities in children with Kawasaki disease in Japan. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5(6):e2216642. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.16642

- Ram Krishna M, Sundaram B, Dhanalakshmi K. Predictors of coronary artery aneurysms in Kawasaki disease. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2014;53(6):561–5. doi: 10.1177/0009922814530802

- Tam H, Tal TE, Go E, Yeung RSM. Pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19: A spectrum of diseases with many names. CMAJ 2020;192(38):E1093–6. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.201600

- Henderson LA, Canna SW, Friedman KG, et al. American College of Rheumatology clinical guidance for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with SARS-CoV-2 and hyperinflammation in pediatric COVID-19: Version 3. Arthritis Rheumatol 2022;74(4):e1–20. doi: 10.1002/art.42062

- Berard RA, Tam H, Scuccimarri R, et al; Candadian Paediatric Society, Acute Care Committee. Paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19 (spring 2021 update). Updated May 3, 2021.

- Yousaf AR, Lindsey KN, Wu MJ, et al. Notes from the field: Surveillance for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children—United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024;73(10):225-8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7310a2

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.