Position statement

Improving paediatric medications: A prescription for Canadian children and youth

Posted: Jul 25, 2019

A joint statement with the Rosalind and Morris Goodman Family Pediatric Formulations Centre of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Ste-Justine. (See below for a list of all authors and endorsing organizations.)

Paediatr Child Health 2019 24(5):333–335 (Executive Summary)

Abstract

In Canada, policies governing medication approval and reimbursement are based largely on adult standards, and the evaluation of new medicines employs adult return-on-investment benchmarks. Research funding for adult diseases is often prioritized over that for childhood illnesses. Canada lags other countries in implementing regulatory and research-related reforms that take the unique characteristics of children and youth into account. To ensure that children and youth have timely access to safe, effective medications, including child-friendly formulations, the federal government must pursue paediatric-focused reforms that consider their unique health needs throughout the drug life cycle. Regulatory reform must be guided by principles of fairness and equity, always recognizing that children deserve the same standards of drug safety, efficacy, availability, and access as adults. Paediatric experts must drive evidence-informed change within Health Canada, and across reimbursement agencies, through the establishment of a permanent, appropriately funded Expert Paediatric Advisory Board. Reforms must ensure the proactive collection and review of paediatric evidence and enable the application of paediatric-sensitive standards and benchmarks across all regulatory and reimbursement decision-making. Finally, the government must fully support evidence-informed paediatric prescribing and establish a stable, national infrastructure for paediatric drug research and clinical trials.

Keywords: Health Canada; Medications; Paediatric formulations; Paediatrics; Regulation; Research

Children have a right to receive the highest standards of health care, including optimal treatments for disease [1]. Yet children and youth continue to be under-represented in medication research [2][3], regulation, and commercial product development [4].

Policies governing the development, approval, and reimbursement of medicines are generally designed for adult populations and often neglect the unique characteristics of children and youth. Research funding for adult diseases tends to be prioritized over childhood illnesses because the capacity for, feasibility of, and expected commercial benefit from adult-focused research is presumed to be greater [5]-[7]. New medicines are often evaluated and brought to market based on principles of adult physiology and adult return-on-investment benchmarks, without consideration for the developing child [8]. Consequently, children’s health care lags that of adults, and Canada trails other developed nations in developing and providing access to safe, effective medications for young people [9].

Up to 80% of all medications currently prescribed in Canadian paediatric hospitals are administered ‘off-label’, meaning their use deviates from the dose, route of administration, patient age, or medical indications described in Health Canada-approved monographs [10]-[13]. Moreover, many commonly prescribed paediatric medications must be extemporaneously compounded, because child-friendly formulations (e.g., an oral liquid or low-dose mini-tablet) are not commercially available. Both off-label prescribing and compounding are associated with significant risk, including adverse reactions and efficacy concerns [14][15].

In a landmark report in 2014, the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology [10] made the first significant effort to understand the extent and effect of off-label medication use in Canada, highlighting children as a vulnerable population. That same year, the Council of Canadian Academies published a multidisciplinary expert panel report exploring the state of pharmacotherapy for children in Canada [16]. They concluded that:

- Children are prescribed medications, many of which have not been proven safe and effective for them.

- Children respond to medications differently from adults, so medicines must be studied in and specifically formulated for children.

- Studying medicines in children is both ethically possible and in their best interests.

- The United States (US) and the European Union (EU) offer lessons for Canada in terms of requiring, promoting, and monitoring paediatric medicines research.

- For maximal impact, paediatric medicines research requires established, sustained infrastructure.

Canada’s federal government launched a significant review of existing regulatory policy in 2016 [17], focused on modernization. This commitment provides a unique occasion to rectify long-term, systemic shortcomings and to strengthen and streamline the safety and availability of paediatric medications for the future. To fully realize this opportunity, regulatory reform must be guided by fundamental health care values, including fairness and equity, to ensure that children and youth receive equitable consideration and attention. Expert paediatric leadership must drive evidence-informed change within Health Canada and across reimbursement decision-making bodies. Policies and processes must enhance paediatric data-gathering and utilization. Finally, the unique needs of children and youth must be considered throughout the drug life cycle. Children deserve the same high standards of drug safety, efficacy, availability, and access as adults.

Current Canadian policies and practices

Health Canada approval

Health Canada has exclusive authority to approve medications for sale in Canada [18]. Their mandate includes new chemical entities, review of products originating in other jurisdictions but new to the Canadian market, and new indications or formulations for medications already available in Canada. Strict, rigorous regulations ensure the safety and efficacy of medicines approved for sale, with a product label that accurately outlines appropriate use.

Similar to regulatory regimes in comparable international jurisdictions, the process of preparing a submission to Health Canada can be lengthy and expensive. Submissions require data summarizing clinical safety and efficacy in the target population, manufacturing process information, quality standards, and non-clinical studies that support safe human use [19]. Typically, a submission requires several large clinical trials (often multi-centre studies involving hundreds of patients), conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice standards established by the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) [20], and using well defined, evidence-based end points. Health Canada may also request additional information that requires additional studies.

While such standards are in place to protect the health of all Canadians, current policies have unintended negative implications for children and youth. Current regulatory norms are based on available data for adult populations, which stem from large patient pools and a stable, well-funded clinical trial infrastructure. At present, parallel trials in paediatric populations may not be feasible, due to low disease prevalence (e.g., total patient numbers) or other systemic barriers to paediatric research. Policy reform and focused, sustained investment are needed to effectively overcome these barriers.

The financial and human resources required to prepare a submission to Health Canada are significant, and the financial benefits anticipated by manufacturers, given Canada’s small paediatric market, can discourage investment [21]. Perceived procedural complexity and the inherent uncertainty of success are additional disincentives. While some accommodations, incentives, and alternative pathways exist [22], they are limited in scope, poorly understood, and rarely used.

Most importantly, Health Canada does not require manufacturers to submit paediatric data unless a specific paediatric indication is being pursued. In stark contrast to leading international jurisdictions, Health Canada does not actively request paediatric evidence, even when use among children and youth can be readily anticipated, or when paediatric data exist and such data have been submitted to other foreign regulators. This passive standard can be considered regulatory neglect, leaving prescribers with limited options and uncertain of how best to modify adult medications to treat children and youth [23].

Off-label drug use

While estimates vary by jurisdiction, practice setting, and speciality, off-label prescribing for paediatric patients is high [24]-[26], particularly in infants [27], children receiving intensive care [28], and children being treated for mental illness [29]. While ‘off-label’ does not necessarily mean ‘off-evidence’ (which is often the case with adult patients), the relative lack of data supporting paediatric efficacy, dosing, and safety can lead to treatment failure, prescribing errors, and adverse events in children [30][31].

Given the cost, complexity, and uncertainty associated with current regulatory processes, there are tacit incentives to adhere to minimum requirements for file submissions. Because Health Canada does not require manufacturers to supply data supporting potential paediatric use unless a paediatric-specific indication is being pursued, omission is a manufacturer’s ‘path of least resistance’. Systemic barriers to commercializing new paediatric drugs or new indications for existing medications, even when they have been approved for paediatric use for decades in trusted markets elsewhere, are significant. The current framework fuels off-label prescribing and endangers children.

Challenges and risks associated with compounding

When a commercially available child-friendly formulation (e.g., an oral liquid) is not available, adult medications are often manipulated to achieve a desired dose or to ease administration, a process known as ‘compounding’. Pharmacy compounding is regulated by provincial/territorial pharmacy standards in Canada and is considered an essential practice [32]. Caregivers may also be advised by a health care provider to compound a medication at home to facilitate administration.

The prevalence of compounding for children in Canada is not precisely known, but it is believed that many of the 80% of all paediatric prescriptions that fall outside of regulatory approval are due to pharmacy compounding or modification by caregivers [16]. Quality controls for compounded products are weaker than for commercially prepared products [33]. Consequently, their stability, potency, uniformity, chemical purity, microbial sterility, and bioavailability are less certain, and significant concentration-related or dosing errors can occur [34]. Because compounded medicines often have an unpleasant taste [35], adherence can be a challenge. And importantly, the manipulation of prescribed but potentially hazardous substances, such as chemotherapeutic agents, can pose significant risk to both patients and family members.

In many cases, paediatric formulations that are commercially available in places like the US and EU are simply not marketed in Canada because of the complex and cumbersome regulatory and reimbursement environment, commercial limitations inherent to a small market, and existing practice norms. Medications for children in Canada deserve the same regulatory protections as medications for adults, and barriers to the commercialization of child-friendly formulations should be eliminated.

Rare diseases and high-cost medications

Under the current regulatory framework, a significant number of medications for rare diseases have not been (nor are likely to be) submitted for Health Canada approval. This gap has created a disproportionate dependency on the federally supported Special Access Programme (SAP), designed to facilitate access to essential medications not marketed in Canada. The SAP review process is cumbersome, time-consuming, case-based, and only accessible by patients for whom no other therapeutic option exists [36].

The evolution of new drug pricing practices has stimulated interest in regulatory approval for selected rare disease medications [37][38]. However, the unintended effects of approving new, sometimes costly medications to replace SAP-accessible options include flooding the market with therapeutics that, in some cases, cost much more but only confer marginal therapeutic benefit compared with older, less expensive products. Ensuring that new drug submissions are reviewed in accordance with current clinical care standards is essential to protect against predatory pricing or practices that have evolved in other jurisdictions. Integrating medication approvals with pricing processes is necessary to support and sustain Canada’s health system over the long term [39].

Beyond Health Canada: Pricing and reimbursement processes

Regulatory approval by Health Canada does not guarantee eligibility for reimbursement under public (or private) drug plans. Public reimbursement status involves four independent steps:

- A Health Technology Assessment (HTA), conducted by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) (in all jurisdictions except Quebec) or the Institut National d’Excellence en Santé et Services Sociaux (INESSS) (in Quebec). Both agencies provide reimbursement recommendations (positive, conditional, or negative) and scope of coverage recommendations to ensure that each medication’s therapeutic and economic value justifies public funding.

- A pricing review, conducted by the Patented Medicines Pricing Review Board (PMPRB) [39]. This federally mandated, quasi-judicial body ensures that prices for patented medicines sold in Canada are not excessive [40].

- A national pricing negotiation by the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA). This association is responsible for maximizing net bulk purchase benefits.

- Independent provincial/territorial/federal program reviews, to determine appropriateness for listing on the public formulary.

This process is designed to optimize procurement controls and help sustain the public health system. However, the current, complex reimbursement assessment system often has the unintended consequence of jeopardizing access to medications and child-friendly formulations for Canadian children and youth. Their unique needs are not systematically considered, nor are paediatric-specific standards and benchmarks routinely employed.

No public reimbursement entity, at any government level, is required to consider the unique attributes of paediatric patients. HTA and pricing negotiations are based on approved indications, which often address the adult population exclusively. Their assessments rely on principles, benchmarks, and price-to-volume ratios based on adult norms, often involving large patient populations with common conditions. They do not usually consider characteristics specific to paediatric populations, which include limited labelling, small market size, lack of clinical and cost-effectiveness data needed to ensure reimbursement, the need for child-friendly formulations, and the shared social benefits of providing quality care for children [41]. Such factors can compromise paediatric-sensitive HTAs for all medications, but become more pronounced when evaluating medications for conditions that primarily or exclusively impact children.

Reforming the HTA and pricing processes in parallel with regulatory improvements will optimize health care and outcomes for paediatric patients.

International best practices

Both the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are empowered to demand paediatric studies when a drug is likely to be used in children, and they receive funding to provide incentives for such work. Health Canada should have a comparable mandate [42].

In Europe, the Paediatric Regulation came into force in 2007, with the aim of increasing the development and availability of safe, effective medicines for children [43]. Central to this initiative is the Paediatric Investigation Plan (PIP) [44], a mandatory component for all drug submissions to provide paediatric data in support of paediatric indications when use in children can reasonably be expected. The PIP requirement applies to new drug submissions and those for new indications, formulations, or routes of administration. For new chemical entities, the PIP is negotiated early (Phase 1 or 2) in the development of a product. For existing entities, a PIP is negotiated as soon as any new indication or dosage is sought. For products with no foreseeable paediatric use (e.g., medications for senile dementia), a formal waiver must be granted [44]. The standing Paediatric Committee (PDCO), a scientific committee responsible for coordinating EMA activities around paediatric medicines, reviews and approves each PIP, and determines the studies to be conducted as part of the proposal. PIP requirements are binding on the manufacturer [44][45].

The US FDA supports a standing Pediatric Review Committee (PeRC) charged with co-ordinating activities related to the development of safe, effective medicines for children [46]. The PeRC is granted authorities through:

- The Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA), which grants the FDA authority to require paediatric studies for certain drugs and biological products, obtain appropriate labelling, and ensure commercial formulation development as needed.

- The Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA), which provides incentives, including market exclusivity, to sponsors who voluntarily complete paediatric clinical studies [47]. The BPCA also prompts the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to identify drugs no longer under patent that require study in children due to a lack of dosing, safety, or efficacy data. The FDA works collaboratively with the NIH to ensure that data from clinical studies is considered for labelling.

At present, the US is pursuing legislation to expand requirements for assessing medication use in paediatric populations, especially for medications used to treat paediatric cancer patients [48]. This landmark work shows how government regulations can ensure safer, more effective paediatric medications.

Fundamental to both the EU and US frameworks are close, coordinated, relationships among regulators, research funders, clinical leaders, and industry [49]. At the centre of each model is a standing committee of paediatric experts, mandated to lead and oversee process, foster stakeholder relationships, and drive change. Central to their effectiveness is a proactive paediatric data-gathering approach to support appropriate labelling, indications, and formulations [51]-[53].

Calls for change

Expert governance: Co-ordinating paediatric leadership

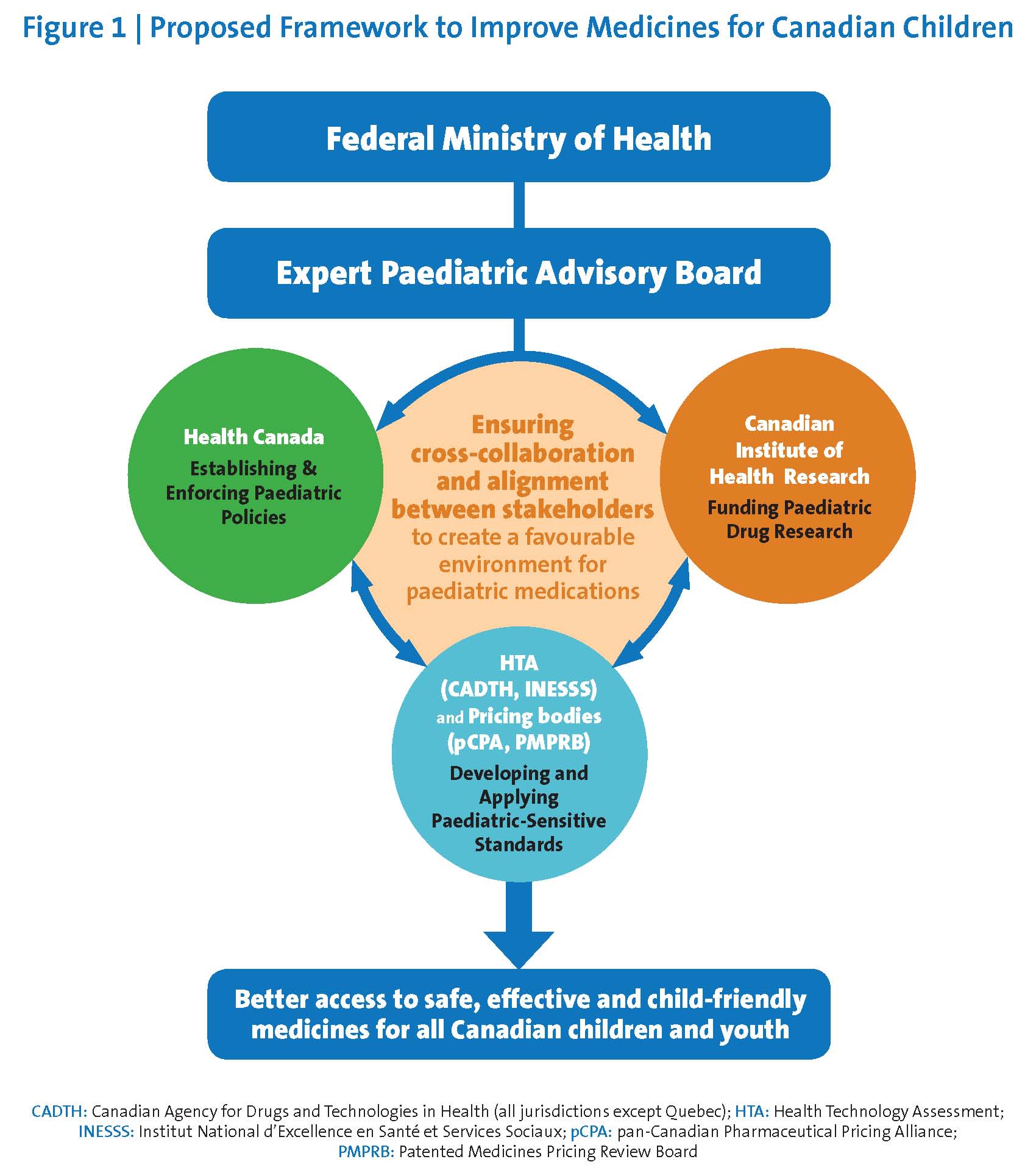

The federal government should establish a permanent, dedicated, appropriately funded Expert Paediatric Advisory Board (‘EPAB’) to review, guide, and co-ordinate activities related to paediatric medication approvals, associated clinical research, and reimbursement activities (Figure 1). The EPAB would:

- Assist Health Canada in developing policies and procedures to proactively identify and address gaps related to paediatric medication use in all drug submissions.

- Support Health Canada, HTA agencies, and pricing or provincial/territorial listing bodies in defining and applying paediatric-sensitive standards of evidence, while recognizing the needs for rigorous scientific inquiry and replicable clinical data, as well as the unique epidemiological and clinical realities of paediatric care.

- Collaborate with Health Canada to develop a paediatric-sensitive approach to using data from trusted foreign jurisdictions and to expedite access to paediatric medications and child-friendly formulations in widespread use on other developed nations.

- Prioritize paediatric medications and formulations for review by Health Canada, including those accessed through the SAP.

- Advise Health Canada, across all portfolios, on issues related to paediatric health investment, policy development, regulatory renewal, and process implementation.

- Co-ordinate paediatric medicine-related activities among stakeholders and throughout the paediatric drug life cycle.

The EPAB should be established at the portfolio level and report directly to both the Minister and Deputy Minister of Health. The Board should include leadership from clinical, academic and administrative domains, with capacity to rapidly assemble ad hoc expert panels when specific questions arise. Public, parent, and patient engagement should be deliberate to assist with both priority-setting and decision-making. Deliberations must be transparent, with an online annual report showing progress toward specific goals and measurable objectives.

Regulatory systems: Process redesign for paediatrics

Regulatory processes must be reformed to better integrate approval, HTA, and pricing processes.

To that end, Health Canada should:

- Be empowered to proactively solicit and review paediatric-specific data for all medication-related submissions where paediatric use is expected or anticipated.

- Consider financial incentives to increase paediatric medication submissions, including submissions for off-patent medications that cannot benefit from market exclusivity or intellectual property protections.

- Work collaboratively with research funders when additional clinical data are required to support specific paediatric submissions. Dedicated funding to support paediatric clinical trials, drug registries and post-market drug studies should align with health policy priorities, bridge paediatric evidence gaps, and optimize output across the health care system.

- Develop, apply, and evaluate innovative approaches and best evidence standards that meet the needs of children and youth [54]. Guidelines developed by and with trusted international partners can advance safe, effective medication use in Canada and around the world [53].

- Engage in regular dialogue with manufacturers on questions of regulatory process, and with reimbursement agencies on paediatric-specific standards and benchmarks.

Clear, paediatrics-specific guidance on regulatory and reimbursement processes must be disseminated to all stakeholders. Along with appropriate HTA review, these reforms will lower barriers, costs, and uncertainty, and draw more paediatric submissions to Canada.

BILL C-17: An opportunity to make paediatric medications accessible, safe, and specific

The 2014 Protecting Canadians from Unsafe Drugs Act (Bill C-17: “Vanessa’s Law”) introduced amendments to the Food and Drugs Act that enhance medication safety by strengthening oversight throughout the drug life cycle, improving reporting systems for adverse events, and increasing transparency [55]. Regulatory proposals associated with Bill C-17 have been slow to emerge, but key reforms must include empowering the Minister of Health to:

- Require manufacturers to provide additional information, perform new clinical studies, and change product monographs when significant safety risks are identified. Investigations may include revising indications or dosages when off-label prescribing presents a serious danger, or when a clear risk is associated with compounding a specific medication (e.g., a cytotoxic drug).

- Authorize the import, manufacture, or preparation of a product for children when a specific, urgent, therapeutic need is identified.

These powers align with key initiatives designed to improve access to safe, effective paediatric medications and should be leveraged appropriately.

Reimbursement systems: The need for process redesign

Efforts to modernize and streamline regulatory processes will remain limited unless the HTA agencies also embrace parallel reforms. Reform-related activities should be guided by paediatric experts who also advise and liaise with federal pricing bodies. This role best belongs to the EPAB, who would be mandated with aligning regulatory, HTA, and reimbursement policy standards and processes. Their specific objectives are to:

- Develop, apply, and evaluate paediatric-sensitive standards of clinical and economic evidence to inform HTAs and pricing processes. These standards should be informed by pharmacological, socio-economic, organizational, and ethical considerations, and must consider evaluations of new paediatric products, indications, and formulations both for on-patent and off-patent medications.

- Ensure that risks associated with compounding are fully considered when evaluating risks and benefits of medications [56], with focus on safety, dose flexibility, and regimens that optimize adherence (including palatability).

- Proactively identify priority medications and formulations that are not currently available in Canada and facilitate evaluations toward review and reimbursement.

Child-friendly formulations: Expanding commercial access

The goal of making child-friendly formulations commercially available for all paediatric patients requires investment in the development of new products [57] as well as the development of novel delivery methods (e.g., fast-dissolving tablets or mini-tablets). Such innovations will allow for safer, more accurate, and more acceptable drug administration for children.

Health Canada should ensure that children in Canada gain access to the same safe, effective commercial formulations that are already available in trusted jurisdictions, such as the US and EU. Accessibility requires a Canadian regulatory system that prioritizes review, data from foreign regulators, and paediatric-sensitive reimbursement pathways.

Evidence-informed prescribing: Problems and solutions

At present, many product monographs are outdated, and industry is neither compelled nor incentivized to update them [58]. While prescribers and dispensers have a variety of tools to guide both on- and off-label prescribing (e.g., the Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialities, hospital-based formularies, clinical practice guidelines, and proprietary subscription services), there is no single, evidence-informed, continuously updated, freely accessible resource to guide medication-related decision-making for paediatric patients.

A national online reference for paediatric medicines and compounding standards is needed to reduce variation in treatment, ensure optimal prescribing for common conditions, and share knowledge of best practices in emerging therapies for rare diseases and other clinical conditions [59]. This resource should also enable real-time reporting of adverse events associated with both commercially available and compounded medications. Reporting trends should prompt an examination by experts of post-market data concerning on- and off-label uses for medications in question. This function would facilitate collection of real-world evidence [60] and support evaluation of medicines throughout their life cycle.

Based on their experience in developing drug and therapeutic resources, the Canadian Pharmacists Association, in conjunction with the Paediatric Chairs of Canada, should lead efforts to create this resource, with funding from Health Canada.

Paediatric research: Focus, funding, and framework

Future federal research budgets should include dedicated portfolios for paediatric drug research proportionate to population size and reflective of the anticipated returns on investment from child-focused inquiry [61]. For diseases that impact children primarily or exclusively (e.g., certain inherited neuromuscular disease), or present uniquely in childhood (e.g., systemic inflammatory conditions), improving outcomes in young people is the most cost-effective path to a healthier adult population.

Canada is a recognized leader in clinical pharmacology, paediatric clinical drug trial design, and population health services. Co-ordinated efforts are necessary to sustain existing research programs, translate innovative methods across research domains, and ensure that advances in trial design and network development are understood and applied by regulatory and reimbursement bodies.

To enhance research efficiency, barriers to conducting paediatric clinical trials should be removed. Other efficiencies include reducing unnecessary duplication among research ethics board reviews, enhancing research sharing platforms, and establishing standards to improve data pooling and comparison. Health Canada should remove obstacles associated with studies using current standard-of-care medications by actively re-labelling off-label drugs that are foundational to paediatric clinical trials. With organized, sustained investment in national paediatric clinical trials infrastructure, such as that being forged by the Maternal Infant Child and Youth Research Network (MICYRN), Canada can become a world leader in paediatric research, and attract both commercially led clinical investigations and large-scale private-public partnerships.

RECOMMENDATIONS

To ensure access to safe, effective medications for children and youth, Canada’s Minister of Health should:

- Establish and fund a permanent Expert Paediatric Advisory Board (EPAB) at the Health Portfolio level. Accountable to the Deputy Minister of Health, this Board should advise on regulatory, reimbursement, and research activities related to paediatric medications and therapeutics.

- Direct Health Canada to: (1) Proactively solicit and review paediatric-specific drug data when paediatric use is expected or anticipated; (2) Develop policy pathways to increase submissions for paediatric medications, indications, and formulations; and (3) Work collaboratively with Health Technology Assessment agencies to develop and evaluate paediatric-specific standards and benchmarks for use in both regulatory and reimbursement contexts.

- Direct Health Canada to: (1) Promote the use of reviews and decisions to support the efficient commercialization of priority paediatric medications and child-friendly formulations; and (2) Review the Special Access Program to support timely access to essential medications for children and to identify priority targets for commercialization in Canada.

- Fund the development of a national, comprehensive, continuously updated online resource to support consistent, evidence-informed prescribing in all centres and jurisdictions across Canada.

- Invest in paediatric drug research and clinical trial infrastructure, ensuring alignment between priority regulatory, reimbursement, and research activities.

Acknowledgements: For their thoughtful contributions and careful review, we wish to thank Dr. Mike Dickinson, Ms. Tammy Clifford and Ms. Anne Tomalin. For critical appraisal and important additions, we also wish to thank Dr. Jim Whitlock and Ms. Kathy Brodeur-Robb.

| List of endorsing organizations: | |

|

Goodman Pediatric Formulations Centre |

Canadian Society of Pharmacology and Therapeutics |

PAEDIATRIC DRUGS AND THERAPEUTICS TASK FORCE

Charlotte Moore Hepburn1, Andrea Gilpin2, Julie Autmizguine, Avram Denburg, Denburg, L. Lee Dupuis, Yaron Finkelstein, Emily Gruenwoldt, Shinya Ito, Geert ‘t Jong, Thierry Lacaze-Masmonteil, Deborah Levy, Stuart MacLeod, Steven P. Miller, Martin Offringa, Maury Pinsk, Barry Power, Michael Rieder, Catherine Litalien2

1Canadian Paediatric Society, Ottawa, Ontario; 2The Rosalind and Morris Goodman Family Pediatric Formulations Centre of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Ste-Justine, Montréal, Quebec

References

- UN General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of the Child, 20 November 1989. United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1577, p. 3: www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b38f0.html (Accessed April 29, 2019).

- Rieder M, Hawcutt D. Design and conduct of early phase drug studies in children: Challenges and opportunities. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2006;82(5):1308-14.

- Field MJ, Behrman RE (eds.). Ethical Conduct of Clinical Research Involving Children. Institute of Medicine Committee on Clinical Research Involving Children. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2004.

- Ward RM, Benjamin DK, Davis JM, et al. The need for pediatric drug development. J Pediatrics 2018;192(1):13-28.

- Hay WW, Gitterman DP, Williams DA, Dover GJ, Sectish TC, Schleiss MR. Child health research funding and policy: Imperatives and investments for a healthier world. Pediatrics 2010;125(6):1259-65.

- Zylke JW, Rivara FP, Bauchner H. Challenges to excellence in child health research: Call for papers. JAMA 2012;308(10):1040-1.

- Tishler CL, Reiss NS. Pediatric drug-trial recruitment: Enticement without coercion. Pediatrics 2011;127(5):949-54.

- Vitiello B, Jensen PS. Medication development and testing in children and adolescents. Current problems, future directions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997;54(9):871-6.

- Joseph PD, Craig JC, Caldwell PH. Clinical trials in children. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015;79(3):357-69.

- Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology. Prescription Pharmaceuticals in Canada: Off-label use. January 2014: https://sencanada.ca/content/sen/Committee/412/soci/rep/rep05jan14-e.pdf (Accessed April 29, 2019).

- Stafford RS. Regulating off-label drug use — Rethinking the role of the FDA. N Engl J Med 2008;358(14):1427–9.

- Pandolfini C, Bonati M. A literature review on off-label drug use in children. Eur J Ped 2005;164(9):552-8.

- Yackey K, Stukus K, Cohen D, Kline D, Zhao S, Stanley R. Off-label medication prescribing patterns in pediatrics: An update. Hosp Pediatr 2019;9(3):186-93.

- Zito JM, Derivan AT, Kratochvil CJ, Safer DJ, Fegert JM, Greenhill LL. Off-label psychopharmacologic prescribing in children: History supports close clinical monitoring. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2008;2(1):24.

- Rawlence E, Lowey A, Tomlin S, Auyeung V. Is the provision of paediatric oral liquid unlicensed medicines safe? Arch Dis Child Educ Prac Ed 2018;103(6):310-3.

- Council of Canadian Academies. Expert Panel on Therapeutic Products for Infants, Children, and Youth. Improving Medicines for Children in Canada, 2014: https://www.scienceadvice.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/therapeutics_fullreporten.pdf (Accessed April 29, 2019).

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. Regulatory Reviews and Modernization: https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/corporate/transparency/acts-regulations/consultation-regulatory-modernization.html (Accessed April 29, 2019).

- Government of Canada. Office of Submissions and Intellectual Property (OSIP): How Drugs are Reviewed in Canada: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/fact-sheets/drugs-reviewed-canada.html (Accessed April 29, 2019).

- Health Canada. Guidance Document: Preparation of Drug Regulatory Activities in the Electronic Common Technical Document Format, May 14, 2015: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/applications-submissions/guidance-documents/ectd/preparation-drug-submissions-electronic-common-technical-document.html (Accessed April 30, 2018).

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use: https://www.ich.org/home.html (Accessed April 29, 2019).

- WorldAtlas, Society, Biggest Pharmaceutical Markets by Country, April 2017 https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/countries-with-the-biggest-global-pharmaceutical-markets-in-the-world.html (Accessed May 13, 2018).

- Health Canada. Guidance Document: Data Protection under C.08.004.1 of the Food and Drug Regulations, May 16, 2017: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/applications-submissions/guidance-documents/guidance-document-data-protection-under-08-004-1-food-drug-regulations.html#a28 (Accessed April 29, 2019).

- Peterson B, Hébert PC, MacDonald N, Rosenfield D, Stanbrook MD, Flegel K. Industry’s neglect of prescribing information for children. CMAJ 2011;183(9): 994-5.

- ‘T Jong GW, Eland IA, Sturkenboom MC, van den Anker JN, Stricker BH. Unlicensed and off label prescription of drugs to children: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2002;324(7349):1311-2.

- Bücheler R, Schwab M, Mörike K, et al. Off label prescribing to outpatient children in primary care in Germany: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2002;324(7349):1311-2.

- Corny J, Bailey B, Lebel D, Bussières JF. Unlicensed and off-label drug use in paediatrics in a mother-child tertiary care hospital. Paediatr Child Health 2016; 21(2):8387.

- Mulugeta YL, Zajicek A, Barrett J, et al. Development of drug therapies for newborns and children: The scientific and regulatory imperatives. Pediatr Clin N Am 2017;64(6):1185-96.

- Czaja A, Reiter PD, Schultz ML, Valuck R. Patterns of off-label prescribing in the pediatric intensive care unit and prioritizing future research. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther 2015;20(3):186-96.

- Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, Gardner JF, Boles M, Lynch F. Trends in the prescribing of psychotropic medications to preschoolers. JAMA 2000;283(8):1025-30.

- Kimland E, Odlind V. Off-label drug use in paediatric patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2012;91(5): 796-801.

- Bellis JR, Kirkham JJ, Nunn AJ, Pirmohamed M. Adverse drug reactions and off-label and unlicensed medicines in children: A prospective cohort study of unplanned admissions to a paediatric hospital. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;77(3):545-53.

- Falconer JR, Steadman KJ. Extemporaneously compounded medicines. Aust Prescr 2017;40(1):5-8.

- Ivanovska V, Rademaker CM, van Dijk L, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK. Pediatric drug formulations: A review of challenges and progress. Pediatrics 2014;134(2):361-72.

- Bussières JF, Héraut MK, Duong MT, et al. Patient access to compounded drugs in pediatrics after discharge from a tertiary center. Pediatr Child Health 2017;22(Suppl 1):e29-e30.

- Lin D, Seabrook JA, Matsui DM, King SM, Rieder MJ, Finkelstein Y. Palatability, adherence and prescribing patterns of antiretroviral drugs for children with human immunodeficiency virus in Canada. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20(12):1246-52.

- Houston AR, Blais CM, Houston S, Ward BJ. Reforming Canada’s Special Access Programme (SAP) to improve access to off-patent essential medicines. Journal of the Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada 2018;3(2):100-7.

- Crowe K. Second Opinion: Canadian families stunned by 3000% increase in price of life-saving drug. CBC News, March 10, 2018: https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/second-opinion-procysbi-cystagon-march10-1.4570152 (Accessed April 29, 2019).

- Pollack A. Parental quest bears fruit in a kidney disease treatment. New York Times, April 30, 2103: https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/01/business/fda-approves-raptor-drug-for-form-of-cystinosis.html (Accessed January 31, 2019).

- Government of Canada. Patented Medicine Prices Review Board. Annual Report 2017: http://www.pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca/view.asp?ccid=1380&lang=en#a5 (Accessed April 29, 2019).

- Government of Canada. Patented Medicine Prices Review Board: http://pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca/home (Accessed January 31, 2019).

- Denburg AE, Ungar WJ, Greenberg M. Public drug policy for children in Canada. CMAJ 2017;189(30):E990-E994.

- MacLeod S. Drug investigation for Canadian children: The role of the Canadian Paediatric Society. Paediatr Child Health 2003;8(4):231-40.

- European Medicines Agency. Human regulatory, overview. Paediatric Regulation: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/paediatric-medicines/paediatric-regulation (Accessed April 29, 2019).

- European Medicines Agency. Human regulatory, research and development/ Paediatric investigation plans: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/paediatric-medicines/paediatric-investigation-plans (Accessed April 29, 2019).

- European Commission. State of Paediatric Medicines in the EU: 10 Years of the EU Paediatric Regulation; Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. COM (2017) 626: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/paediatrics/docs/2017_childrensmedicines_report_en.pdf (Accessed January 31, 2019).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pediatric Review Committee (PeRC): https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/ucm607942.htm (Accessed April 29, 2019).

- Avant D, Wharton GT, Murphy D. Characteristics and changes of pediatric therapeutic trials under the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act. J Pediatr 2018;192:8-12.

- U.S. Senate, Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committees. S.3239 – Research to Accelerate Cures and Equity for Children or the RACE for Children Act: https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/3239 (Accessed April 29, 2019).

- Institute for Advanced Clinical Trials (I-ACT) for Children: https://www.iactc.org (Accessed January 31, 2019).

- European Medicines Agency. Partners and networks: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/partners-networks/networks/european-network-paediatric-research-european-medicines-agency-enpr-ema (Accessed April 29, 2019).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act and Pediatric Research Equity Act: https://www.fda.gov/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/PediatricTherapeuticsResearch/ucm509707.htm (Accessed April 29, 2019).

- Olski TM, Lampus SF, Gherarducci G, Saint Raymong A. Three years of paediatric regulation in the European Union. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2011;67(3):245-52.

- McMahon AW, Dal Pan G. Assessing drug safety in children – The role of real world data. N Engl J Med 2018;378(23):2155-7.

- van der Lee JH, Wesseling J, Tanck MW, Offringa M. Efficient ways exist to obtain the optimal sample size in clinical trials in rare diseases. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61(4):324-30.

- Government of Canada. Protecting Canadians from Unsafe Drugs Act (Vanessa’s Law): https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/2014_24.pdf (Accessed May 13, 2019).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine. Characterizing Uncertainty in the Assessment of Benefits and Risks of Pharmaceutical Products: Workshop in Brief (2014): https://www.nap.edu/catalog/21679/characterizing-uncertainty-in-the-assessment-of-benefits-and-risks-of-pharmaceutical-products (Accessed April 29, 2019).

- Gilpin A, Autmizguine J, Allakhverdi Z, et al. A pan-Canadian study on the compounded medicines most in need of commercialized oral pediatric formulations. Paediatr Child Health 2018;23(Issue suppl 1):e53.

- Kelly LE, Ito S, Woods D, et al. A comprehensive list of items to be included on a pediatric drug monograph. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther 2017;22(1): 48-59.

- van der Zanden TM, de Wildt SN, Liem Y, et al. Developing a paediatric drug formulary for the Netherlands. Arch Dis Child 2017;102(4):357-61.

- Health Canada. Strengthening the Use of Real World Evidence for Drugs, August 22, 2018: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/transparency/regulatory-transparency-and-openness/improving-review-drugs-devices/strengthening-use-real-world-evidence-drugs.html (Accessed April 29, 2019).

- Osokogu OU, Dukanovic J, Ferrajolo C, et al. Pharmacoepidemiological safety studies in children: A systematic review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2016;25(8):861-70.

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.