Position statement

A guide to the community management of paediatric eating disorders

Posted: Jun 6, 2024

Principal author(s)

Marian Coret MD, MSc, BSc; Ellie Vyver MD, FRCPC; Megan Harrison MD FRCPC; Alene Toulany MD, MSc, FRCPC; Ashley Vandermorris MD, MSc, FRCPC; Holly Agostino MD, Adolescent Health Committee

Abstract

Eating disorders (EDs) are a group of serious, potentially life-threatening illnesses that typically have their onset during adolescence and can be associated with severe medical and psychosocial complications. The impact of EDs on caregivers and other family members can also be significant. Health care providers (HCPs) play an important role in the screening and management of adolescents and young adults with EDs. This position statement assists community-based HCPs with recognizing, diagnosing, and treating EDs in the paediatric population. Screening modalities, indications for hospitalization, medical complications, and monitoring of young people with EDs are summarized. Current evidence supports the use of family-based treatment (FBT) as the first-line psychological therapeutic modality for adolescents with restrictive EDs. While the provision of FBT may be beyond the scope of practice for some community physicians, this statement reviews its core tenets. When an ED is diagnosed, early application of these principles in the community setting by HCPs may slow disease progression and provide guidance to families.

Keywords: Anorexia; Eating Disorder; Family-based Treatment

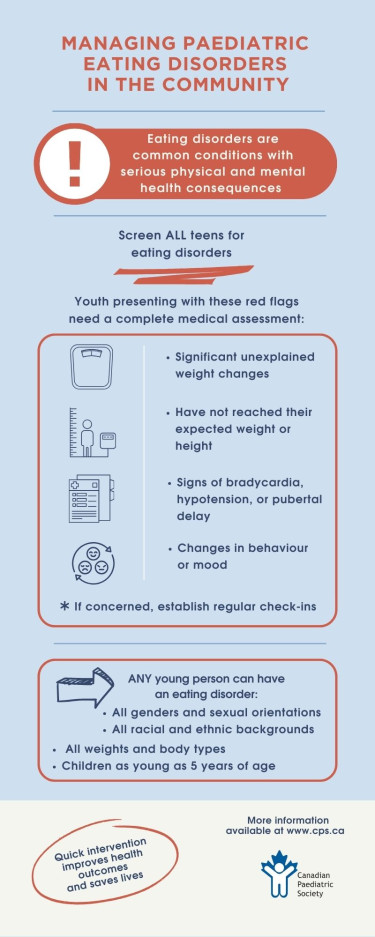

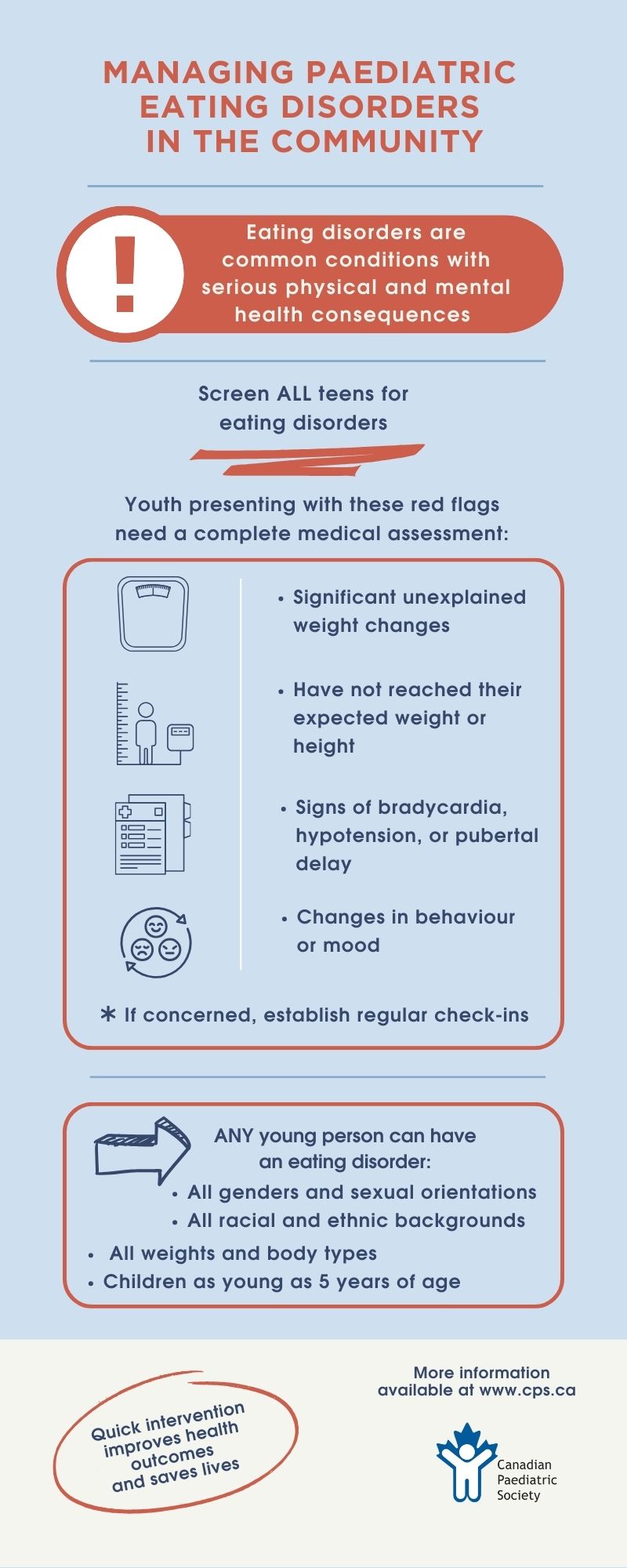

Prevalence and populations

Eating disorders (EDs) are a group of heterogenous illnesses that significantly impact the psychosocial and medical health of children and adolescents in Canada[1]. EDs affect youth of all ages, genders, sexual orientations, racial/ethnic identities, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Compared with age-matched controls, youth with EDs are at a significantly higher risk of morbidity and mortality[2]. EDs can lead to complex and even life-threatening complications, with anorexia nervosa (AN) having the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder[3][4].

It is estimated that up to 5% of adolescents in Canada are affected by EDs[5]. Yet despite this prevalence, many youth with an ED go unrecognized or experience delays in diagnosis. Missed or delayed diagnoses often occur in populations that do not fit the classic ED phenotype, such as males, sexual or racial minorities, pre-pubertal children, or individuals perceived to be of average or above average weight[6]. It is increasingly recognized that many adolescents who present with atypical AN (i.e., those with significant weight loss but with a normal or elevated body mass index (BMI)), are either overlooked by health care providers (HCPs) as having an ED or perceived as being less at risk for complications. However, the research suggests that individuals with atypical AN experience similar rates of medical instability and complications and higher degrees of ED psychopathology and morbidity compared with those who are underweight[7].

Young people may also present with restrictive EDs that are unrelated to weight or body image concerns. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is an ED associated with a persistent disturbance in feeding and eating that results in an inability to meet nutritional or energy needs. Individuals may present with a lack of interest in eating or limited variety of intake secondary to sensory sensitivity or from a fear of aversive consequences from eating (e.g., choking or vomiting)[3][8].

Over the past decade, the incidence of adolescent EDs has gradually continued to rise[9]. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic led to significant increases in both the prevalence and severity of restrictive EDs in paediatric populations[10]-[13]. The global surge in EDs has caused significant challenges to accessing tertiary level services and highlighted the need to increase the capacity of community providers to care for youth with EDs[14].

Enhancing the role of community HCPs

Community HCPs can play an important role in the screening, assessment, and management of EDs among youth. Studies have shown that most youth with EDs present first to their primary care provider, sometimes with vague symptoms such as abdominal pain, fatigue, or menstrual abnormalities[15]. Preventative health care visits are regular opportunities to screen for ED behaviours as part of the psychosocial assessment[14]. Community HCPs have considerable expertise in coaching caregivers to engage in essential health behaviours (e.g.vaccinations, medication adherence), making them well equipped by experience to help patients and families implement behaviour changes[16]. Trust built during their longitudinal relationships with patients can benefit and support family-centred care and treatment implementation.

Routine ED screening and early intervention can be complicated by numerous barriers, including scarcity of resources, time limitations, and lack of physician confidence in recognizing and treating these disorders[17]. Surveys of primary care paediatricians and family physicians found that while most respondents felt they had a role in screening and assessing EDs, they often failed to identify these conditions[18][19]. Moreover, fewer than half reported feeling confident in their ability to effectively intervene[17][20]. Adolescents with EDs may deny the symptoms and severity of their illness, or avoid care, making diagnosis more challenging[21]. Despite these challenges, community HCPs are well positioned to pick up the early warning signs of EDs. Because timely intervention leads to improved ED outcomes[22], they also have a unique opportunity to slow disease progression by educating and counselling to implement behavioural changes early in the course of illness.

Timely screening and diagnosis

Early recognition and diagnosis of EDs is associated with improving prognosis[22], and all adolescents should be screened for EDs at yearly health supervision visit[2]. HCPs are encouraged to use structured psychosocial history-taking approaches (Table 1), which incorporate questions focused on diet, weight, and body image [23][24]. ED-specific screening questionnaires such as the SCOFF[25] or the Eating Disorder Screen for Primary Care [26] (Table 1) can also be used with older adolescents[27].

Table 1. Examples of screening questions for adolescent eating disorders

|

As part of the HEEADSSS/SSHADESS history |

Does your weight or body shape cause you stress? How do you feel about your body – is there anything you want to change? Have there been any recent changes in your weight? Have you had any desire to change your weight? Are you exercising right now? Do you feel comfortable missing a day here and there? Does your exercise feel out of control? Have others expressed concerns about your eating, exercising or weight? |

|

SCOFF Questionnaire |

Do you make yourself vomit (Sick) because you feel uncomfortably full? Do you worry you have lost Control over how much you eat? Have you recently lost more than 15 pounds (One stone) in a three-month period? Do you believe you are Fat when others say you are too thin? Would you say that Food dominates your life? (Yes = 1 point; No = 0 points) (Scoring ≥2 indicates higher risk of anorexia nervosa or bulimia) |

|

Eating Disorder Screen for Primary Care |

Are you satisfied with your eating patterns? Do you ever eat in secret? Does your weight affect the way you feel about yourself? Have any members of your family suffered with an eating disorder? Do you currently suffer with, or have you ever suffered with an eating disorder? |

Young people reporting behaviours suggestive of EDs on screening tests should have a detailed history taken to clarify the diagnosis[2]. Table 2 provides an approach to initiating an ED-focused intake questionnaire. Concerning behaviours for EDs include serious body image concerns, desire for weight loss, fear of weight gain, restrictive or binging eating patterns, purging behaviours, excessive exercise, and use of pharmacotherapy for weight loss or altering appearance. Compulsive exercise, exercise associated with food intake, or guilt when unable to exercise are also strongly suggestive of ED symptomatology[28].

|

General

Time frame

Dietary history Obtain longitudinal growth points whenever possible (e.g., previous care providers, hospital visits, allied health professionals).

Eating disorder cognitions

Binging/purging behaviours:

Exercise history:

Review of systems related to EDs Any history of the following symptoms?

Screen for common comorbidities

|

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) provides diagnostic criteria for common EDs seen in adolescence[29]. Even when not all diagnostic criteria are met, EDs may present in subclinical forms with significant functional and medical impairment. It is important to consider that depending on disease insight, children and adolescents with EDs may not recognize or be ready to acknowledge ED symptomatology[21]. Thus, obtaining a collateral history from a parent or caregiver regarding behaviours may help toward formulating an ED diagnosis[30].

Screening for EDs at health maintenance visits should also include a physical examination. At each health care encounter, anthropometric data including weight, height, and BMI should be collected and plotted on age-appropriate growth curves and reviewed for concerning trends. All children and adolescents, including those with normal or elevated BMI, who present with significant unexplained weight changes, who have not reached their expected weight or height, or who show signs of bradycardia, hypotension, or pubertal delay, should receive a comprehensive medical assessment and be screened for a possible underlying ED[27]. Orthostatic vital signs should be obtained after having the patient lie supine for 5 minutes and repeated after 3 minutes of standing. In adolescents, changes consistent with malnutrition may include bradycardia (daytime heart rate <50 bpm), hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90), hypothermia (core body temperature <35.6°C), and orthostatic variations (postural drop in systolic BP >20 mm Hg or postural drop in diastolic >10 mm Hg, and/or heart rate increase >30 bpm)[31].

Initial laboratory investigations should be considered for all youth with a suspected ED to rule out other organic etiologies and assess for medical complications related to the ED (Table 3). Diseases that may mimic EDs in youth include celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, hyperthyroidism, type 1 diabetes mellitus, adrenal insufficiency, systemic lupus erythematosus, chronic infection, and neoplasms[32]. Often, laboratory investigations of individuals with restrictive EDs reveal no abnormalities, even when medical and psychological morbidity are severe.

Ongoing medical care for children and adolescents with EDs

When an ED diagnosis has been established, regular check-ins with the patient and family to monitor clinical evolution become the cornerstone of care. HCPs should determine the degree of malnutrition. This evaluation can be conducted using either the percent median BMI (current BMI divided by the BMI at the 50%ile), or BMI Z-scores. However, because these values may not capture the true severity of illness in children or youth with atypical AN, the magnitude and rate of weight loss (Table 4) are better measures[31]. The magnitude of weight loss is calculated as a percentage of body weight lost ((usual weight minus presentation weight) divided by usual weight). The rate of weight loss is calculated by dividing the amount by the number of months over which weight loss occurred (percentage of body weight lost divided by months). Current guidelines suggest using increments of 1, 3, 6, and 12 months[31].

Individuals with severe malnutrition should be followed more closely (e.g., biweekly to weekly) for medical complications (Table 5), and referred for subspecialist (e.g., to an eating disorder clinic) or multidisciplinary care (e.g., family therapist, psychiatrist, dietitian), or both[33].

Medical follow-up of patients with EDs should include documentation of vital signs and changes in weight, and evaluation for medical complications. Whenever possible, growth parameters should be measured under standardized conditions, for example using calibrated scales with the patient in a hospital gown. A daily multivitamin and elemental calcium (1300 mg/day for patients 9 to 18 years of age) and vitamin D (600 IU/day) supplementation are recommended for all youth with restrictive EDs[2]. These supplements optimize bone health during weight restoration and address potential underlying micronutrient deficiencies.

Documenting changes in weight is an important aspect of follow-up and guides ongoing care. The frequency of weight checks may vary depending on the severity of presentation. While the experience of being weighed can be emotionally challenging for some individuals, the use of ‘blind’ weight checks (i.e., patients not seeing their weight) is not mandatory. Patient perception and knowledge of weight can be discussed with the family and influenced by stage of illness, progress toward recovery, and patient maturity. Weight changes should be considered in the context of overall function because it is only one indicator of progress toward recovery.

Certain clinical symptoms that suggest medical instability may require inpatient hospitalization for nutritional rehabilitation (Table 6)[31]. Decisions around admission should be based on a comprehensive clinical assessment of an individual’s physical and psychological health, available and accessible outpatient resources, and level of family support. Admission criteria vary among hospitals, and HCPs should be familiar with local or referring centre guidelines.

Family-based treatment approaches

A variety of psychological treatment modalities exist for children and adolescents with EDs. An eating disorder-focused family-based intervention, family-based treatment (FBT), is the first-line approach for restrictive EDs in paediatrics[34]. When available, refer adolescents with a restrictive ED to a specialized FBT provider as soon as possible[35]. FBT is a manualized therapy for outpatients, where the role of the treating team is to assist the family in identifying ED behaviours and empowering parents or caregivers to regain control around nutritional intake. FBT has three phases with distinct goals. Phase 1 focuses on weight restoration through parent-led meals and supervision. Phase 2 returns control of eating back to the adolescent in developmentally appropriate steps. Phase 3 addresses other facets of adolescent development that might be impacted by the ED[36].

In the FBT model, HCPs should request that parents or caregivers assume full control over meal selection until a healthy weight is achieved[36]. Caregivers should oversee the preparation, plating, and supervision of all meals and snacks. Parents should be encouraged to establish a plan of supervision for any meals or snacks eaten at school, either by school personnel or by parents themselves. Children or youth with an ED should not be involved in the selection or preparation of their own meals until they have achieved both a healthy weight and limited ED psychopathology.

By understanding the basic principles of FBT, an HCP can initiate discrete elements of this evidence-based intervention in a “parents-in-charge” framework without engaging in formal therapy. Moreover, parental limit-setting strategies for restrictive EDs may also be applied effectively to other EDs (e.g., bulimia nervosa). At follow-up visits, the HCP may counsel and support families to take control of meal preparation and supervision and educate and empower parents to set limits around ED behaviours. Parental supervision may include post-meal observation (for 30 minutes to 1 hour) of children who engage in purging behaviours. An overview for applying FBT in community outpatient settings is available[33].

Although FBT remains standard treatment for restrictive EDs, it may not be available to, or even appropriate for, all families. Families living with severe emotional dysfunction, high demands of care (e.g., experiencing poverty or parenting alone) or history of abuse are unlikely to respond as effectively to FBT. Also, significant psychiatric comorbidities can challenge and complicate FBT approaches. In such cases, or for non-restrictive ED diagnoses, other therapeutic modalities may be preferable[35].

Nutritional guidance

For youth with restrictive eating disorders, determining a treatment goal weight (TGW) is helpful to guide nutritional rehabilitation. The TGW is a weight range that adequately supports healthy, regular eating patterns, pubertal development, growth, physical activity, and psychosocial functioning[37]. This range can be estimated by reviewing serial weights taken pre-ED (using previous growth charts or historical information provided by the family) to determine total weight loss over a specific period of time. TGWs are estimates and should be reassessed every 3 to 6 months as a patient matures and treatment progresses. For a detailed approach, see the Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) practice point “Determining treatment goal weights for children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa”[37].

For outpatient nutritional rehabilitation, guidance should focus on the healthy intake of regular meals, typically three meals and three snacks per day. Within an FBT model, meal plans that specify caloric goals per day are not recommended[2][36], and detailed tracking of caloric intake is not necessary. Special diets that did not pre-date disordered eating (e.g., vegetarian or vegan diets) are often a symptom of an ED, and may make meeting nutritional goals especially challenging. Encourage families to serve foods with high caloric density and energy-rich beverages (e.g., choosing fruit juice or milk instead of water) to maximize energy intake without necessitating large increases in volume. When weight restoration is required, a weight gain of 250 g to 500 g per week is considered appropriate in the outpatient setting. Typically, adolescents require 2000 to 3000 kcal/day to meet these goals[33]. As treatment progresses, daily caloric demand may increase as physiologic processes resume. HCPs should assist parents and caregivers with adjusting portion size and energy density based on weight progress. If weight is not increasing, the physician, together with the family, should try to ascertain why and help strategize on how best to improve results. A ‘re-set’ may include reducing or stopping activities or increasing meal supervision and portion sizes.

Establishing an eating routine where each meal and snack is eaten at approximately the same time every day facilitates a return to normal metabolism and natural hunger and satiety cues. Parents or caregivers should also be encouraged to progressively reintroduce foods that have been avoided or that induce fear of weight gain.

Activity restrictions

Individuals in an acute and medically compromised state should not be engaging in physical activity, regardless of age, weight, or athletic ability[2]. In EDs this critical state may include recent episode(s) of fainting, vital sign changes, multiple daily binge-purge episodes, inadequate nutritional intake, or chronic dehydration. Even when vital signs are within normal range, FBT encourages families to set limits around any activity they feel may impede their child’s recovery or ability to gain weight. Patients often need to be exempted from the gym or temporarily removed from sports teams and activities (or both) until TGW is reached. When they return to physical activity, a gradual reintroduction and close monitoring of weight and vital signs are recommended. Nutritional intake may need to be adjusted to prevent relapse. HCPs should assist families in promoting activities that are social, time-limited, and emotionally positive.

Providing family support and guidance

Early family interventions should focus on psychoeducation around the risks of malnutrition and on helping parents set limits around ED behaviours. In the FBT model, “heightening anxiety” around the ED diagnosis and potential dangers to health is recommended[36]. Highlighting the seriousness of this disease to families can be a driver for change[34], and HCPs are encouraged not to minimize or downplay ED risks.

A core tenet of FBT is the separation or “externalization” of the ED from the person living it, which targets the disorder as the cause of family conflict as opposed to the child or adolescent with the ED (i.e., “It’s not your child fighting and resisting your efforts to help—it’s the illness”). During treatment, families often report that mealtimes become tense due to arguments. HCPs should empower families to externalize the ED in these moments and not negotiate or give in to demands. For restrictive EDs, HCPs can adopt a “food as medicine” approach with families, prescribing food as non-optional. Encourage parents to insist on family meals, with a common meal for all family members, including the patient. Distraction techniques during meals (e.g., talking about other subjects) or adopting a mechanical eating approach may prove helpful for some. Traditional behavioural modification strategies—rewarding desirable behaviours and providing consequences for undesirable behaviours—can also be useful[33]. For example, privileges such as going out with friends or attending social events can be negotiated depending on cooperation with eating and weight gain. Parents are advised to avoid food or weight-oriented discussions at home.

Generally, adolescents have greater success in recovering from EDs than adults, with overall recovery rates of approximately 70%[38]. However, recovery can be complicated and lengthy. A high proportion of family caregivers present as overwhelmed, exhausted, and hopeless. Most have attempted to address their child’s ED behaviours without success. Validating both the challenges and the vital (but often exhausting) role of the caregiver can help build a therapeutic alliance with HCPs and reinforce adherence to treatment. HCPs need to understand how significantly the long recovery process impacts the quality of life of all family members. Families (including siblings) may also need personal support, and should be encouraged to seek therapy as needed.

Recommendations:

- Adolescents should be screened for eating disorders (EDs) as part of any routine or health supervision visit.

- All children and adolescents, including those with normal or elevated body mass indices (BMIs), who present with a history of significant unexplained weight change, failure to reach an expected weight or height, bradycardia, hypotension, or pubertal delay, should receive a comprehensive medical assessment for a possible underlying ED.

- Individuals presenting with positive findings on screening should have a detailed history, physical exam, and laboratory investigations to clarify the diagnosis and assess for medical complications.

- Children and adolescents with diagnosed EDs should be routinely assessed for vital sign changes, medical complications, and consideration for hospital admission.

- When available, referral to a specialized family-based treatment (FBT) provider should be initiated for restrictive adolescent EDs.

- Health care providers (HCPs) of children or youth with an ED should familiarize themselves with the core concepts of FBT and are encouraged to counsel or initiate elements of this evidence-based intervention in their clinical encounters with families.

- During treatment, nutritional rehabilitation should focus on the regular intake of meals and snacks with supervision by parents or caregivers. HCPs should assist with adjusting portion size and energy density based on weight progress.

- When deemed medically appropriate to return to physical activity, HCPs should assist with promoting activities that are social, time-limited, and emotionally positive.

- HCPs should understand how treatment and recovery processes impact quality of life for all family members, and assist or refer them for therapeutic services or supports as needed.

Acknowledgements

This position statement has been reviewed by the Acute Care, Community Paediatrics, and Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Committees of the Canadian Paediatric Society.

CANADIAN PAEDIATRIC SOCIETY ADOLESCENT HEALTH COMMITTEE (APRIL 2023)

Members: Holly Agostino MD; Marian Coret MD, MSc, BSc (Resident-member); Megan Harrison MD FRCPC; Ayaz Ramji MD (Board-representative); Alene Toulany MD, MSc, FRCPC; Ashley Vandermorris MD, MSc, FRCPC; Ellie Vyver MD, FRCPC (Chair)

Liaison(s): Amy Robinson MD, FRCPC (Adolescent Health Section)

Principal authors: Marian Coret MD, MSc, BSc; Ellie Vyver MD, FRCPC; Megan Harrison MD FRCPC; Alene Toulany MD, MSc, FRCPC; Ashley Vandermorris MD, MSc, FRCPC; Holly Agostino MD

References

- Academy for Eating Disorders Medical Care Standards Committee. Eating Disorders: A guide to Medical Care. 3rd edn., 2016. https://www.massgeneral.org/assets/mgh/pdf/psychiatry/eating-disorders-medical-guide-aed-report.pdf (Accessed January 24, 2024).

- Hornberger LL, Lane MA; American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Committee on Adolescence. Identification and management of eating disorders in children and adolescents. Pediatrics2021;147(1):e2020040279. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-040279.

- Herpertz-Dahlmann B. Adolescent eating disorders: Definitions, symptomatology, epidemiology and comorbidity. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2009;18(1):31-47. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.07.005.

- Franko DL, Keshaviah A, Eddy KT, et al. A longitudinal investigation of mortality in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170(8):917-25. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12070868.

- Canadian Paediatric Society, Adolescent Medicine Committee. Eating disorders in adolescents: Principles of diagnosis and treatment. Paediatr Child Health 1998;3(3):189-96. doi: 10.1093/pch/3.3.189.

- Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, Swendsen J, Merikangas KR. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68(7):714-23. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.22.

- Sawyer SM, Whitelaw M, Le Grange D, Yeo M, Hughes EK. Physical and psychological morbidity in adolescents with atypical anorexia nervosa. Pediatrics 2016;137(4): e20154080. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4080.

- Katzman DK, Guimond T, Spettigue W, Agostino H, Couturier J, Norris ML. Classification of children and adolescents with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Pediatrics 2022;150(3): e2022057494. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-057494.

- Nicholls DE, Lynn R, Viner RM. Childhood eating disorders: British national surveillance study. Br J Psychiatry 2011;198(4):295-301. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.081356.

- Agostino H, Burstein B, Moubayed D, et al. Trends in the incidence of new-onset anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa among youth during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4(12):e2137395. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37395.

- Otto AK, Jary JM, Sturza J, et al. Medical admissions among adolescents with eating disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics 2021;148(4): e2021052201. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052201.

- Toulany A, Kurdyak P, Guttmann A, et al. Acute care visits for eating disorders among children and adolescents after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Adolesc Health 2022;70(1):42-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.09.025.

- Vyver E, Han AX, Dimitropoulos G, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and Canadian pediatric tertiary care hospitalizations for anorexia nervosa. J Adolesc Health 2023;72(3):344-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.07.003.

- Lenton-Brym T, Rodrigues A, Johnson N, Couturier J, Toulany A. A scoping review of the role of primary care providers and primary care-based interventions in the treatment of pediatric eating disorders. Eat Disord 2020;28(1):47-66. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2018.1560853.

- Hoek HW. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2006;19(4):389-94. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000228759.95237.78.

- Lebow J, Narr C, Mattke A, et al. Engaging primary care providers in managing pediatric eating disorders: A mixed methods study. J Eat Disord 2021;9(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s40337-020-00363-8.

- Linville D, Brown T, O’Neil M. Medical providers' self perceived knowledge and skills for working with eating disorders: A national survey. Eat Disord 2012;20(1):1-13. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2012.635557.

- Stein REK, Horwitz SM, Storfer-Isser A, Heneghan A, Olson L, Hoagwood KE. Do pediatricians think they are responsible for identification and management of child mental health problems? Results of the AAP periodic survey. Ambul Pediatr 2008;8(1):11-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.10.006.

- Robinson AL, Boachie A, Lafrance GA. Assessment and treatment of pediatric eating disorders: A survey of physicians and psychologists. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012;21(1):45-52.

- Davis DW, Honaker SM, Jones VF, Williams PG, Stocker F, Martin E. Identification and management of behavioral/mental health problems in primary care pediatrics: Perceived strengths, challenges, and new delivery models. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2012;51(10):978-82. doi: 10.1177/0009922812441667.

- Couturier JL, Lock J. Denial and minimization in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord2006;39(3):212-6. doi: 10.1002/eat.20241.

- Haripersad YV, Kannegiesser-Bailey M, Morton K, et al. Outbreak of anorexia nervosa admissions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Dis Child 2021;106(3):e15. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319868.

- Goldenring JM, Rosen DS. Getting into adolescent heads: An essential update. Contemp Pediatr 2004;21(1):64-90.

- Tylee A, Haller DM, Graham T, Churchill R, Sanci LA. Youth-friendly primary-care services: How are we doing and what more needs to be done? Lancet 2007;369(9572):1565-73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60371-7.

- Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: Assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ 1999;319(7223):1467-8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1467.

- Cotton MA, Ball C, Robinson P. Four simple questions can help screen for eating disorders. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18(1):53-6. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20374.x.

- Feltner C, Peat C, Reddy S, et al. Screening for eating disorders in adolescents and adults: Evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2022;327(11):1068-82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.1807.

- Carpine L, Charvin I, Da Fonseca D, Bat-Pitault F. Clinical features of children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa and problematic physical activity. Eat Weight Disord 2022;27(1):119-29. doi: 10.1007/s40519-021-01159-8.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5-TR. 5th edition, text revision. Washington, DC: APA Publishing; 2022.

- Lock J, La Via MC; American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Committee on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with eating disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;54(5):412-25. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.01.018.

- Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. Medical management of restrictive eating disorders in adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health 2022;71(5):648-54. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.08.006.

- Katzman DK, Gordon C, Callahan T, et al eds.. Neinstein’s Adolescent and Young Adult Health Care: A Practical Guide. 7th edn. Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott; 2023.

- Findlay S, Pinzon J, Taddeo D, Katzman DK. Family-based treatment of children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa: Guidelines for the community physician. Paediatr Child Health 2010;15(1):31-40. doi: 10.1093/pch/15.1.31.

- Rienecke RD. Family-based treatment of eating disorders in adolescents: Current insights. Adolesc Health Med Ther 2017;8:69-79. doi: 10.2147/AHMT.S115775.

- Couturier J, Isserlin L, Norris M, et al. Canadian practice guidelines for the treatment of children and adolescents with eating disorders. J Eat Disord 2020;8:4. doi: 10.1186/s40337-020-0277-8.

- Lock J, Le Grange. Treatment Manual for Anorexia Nervosa: A Family-Based Approach, 2nd edn. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2015.

- Norris ML, Hiebert JD, Katzman DK; Canadian Paediatric Society; Adolescent Health Committee. Determining treatment goal weights for children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Paediatr Child Health 2018;23(8):551-2. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxy133. https://cps.ca/en/documents/position/goal-weights

- Steinhausen HC, Grigoroiu-Serbanescu M, Boyadjieva S, Neumarker KJ, Winkler Metzke C. Course and predictors of rehospitalization in adolescent anorexia nervosa in a multisite study. Int J Eat Disord 2008;41(1):29-36. doi: 10.1002/eat.20414.

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.