Practice point

The management of very mild and mild asthma in preschoolers, children, and adolescents

Posted: Dec 8, 2023

Principal author(s)

Connie Yang MSc MD, Zofia Zysman-Colman MD, Estelle Chétrit MDCM MBA, Anne Hicks MSc PhD MD, Joseph Reisman MD MBA, Amy Glicksman MD, Respiratory Health Section

Paediatr Child Health 29(2):122–126.

Abstract

This practice point summarizes recommendations from the Canadian Thoracic Society’s 2021 ‘Guideline update: Diagnosis and management of asthma in preschoolers, children, and adults’. New recommendations include: a decrease in the frequency of daytime symptoms and reliever use to ≤2 per week in the asthma control criteria; assessing for risk of asthma exacerbation; not using as needed short-acting beta-agonists alone in patients at higher risk for exacerbation; and the option of as needed budesonide/formoterol in those ≥12 years old if they are unable to take daily inhaled corticosteroids despite extensive asthma education and support. The preference for daily inhaled corticosteroids to manage mild asthma in children, and the recommendation against intermittent short courses of inhaled corticosteroids, are unchanged.

Keywords: Asthma; Canadian Thoracic Society; Mild asthma; Very mild asthma

Background

The focus of this practice point is the pharmacological management of very mild or mild asthma in children over a year old, who comprise between 28% and 41% of the paediatric population with asthma. More complete information on the diagnosis and treatment of asthma in preschoolers, children, and adolescents can be found in the Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS) 2021 Guideline update: Diagnosis and management of asthma in preschoolers, children and adults[1], and in their 2015 joint position statement with the Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS)[2]. Over the last 5 years, new literature has been published on intermittent inhaled corticosteroid regimens, and recommendations from the 2021 CTS Guideline – A focused update on the management of very mild and mild asthma[3] are summarized here for paediatricians and primary health care providers (HCPs).

|

Acronyms and abbreviations Bud/form – budesonide/formoterol CTS – Canadian Thoracic Society ICS – inhaled corticosteroids LTRA – leukotriene receptor antagonists NHLBI – National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute PRN – “pro re nata”, meaning “as circumstances arise” or “prescribe-as-needed” SABA – short-acting beta-agonist URTI – upper respiratory tract infection |

What is very mild and mild asthma?

Asthma severity is defined by the level of treatment required to maintain asthma control (Tables 1 and 2) and can fluctuate over time. Severity can only be accurately determined when asthma is well controlled and factors such as adherence and correct inhaler technique have been accounted for.

Asthma is a chronic condition with symptoms that can be intermittent, but all individuals with asthma are at risk for asthma exacerbations, or even death if untreated, regardless of disease severity in individual cases. Terms previously used to describe severity, such as “intermittent” or “mild-intermittent” asthma, are no longer considered appropriate because they misrepresent this ongoing risk.

Table 1. Asthma severity

| Level | Treatment required to maintain control |

| Very mild | PRN SABA |

| Mild | Low-dose ICS (or LTRA) + PRN SABA or PRN budesonide/formoterol |

| Moderate |

Low-dose ICS + a second controller + PRN SABA or moderate doses of ICS +/– a second controller + PRN SABA or low-to-moderate-dose budesonide/formoterol + PRN budesonide/formoterol |

| Severe | High-dose ICS + a second controller or systemic steroids for 50% of the previous year* |

*Severe asthma may not be controlled even with this treatment

ICS Inhaled corticosteroid; LTRA Leukotriene receptor antagonist; PRN Prescribed-as-needed; SABA Short-acting beta-agonist

Table 2. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) dosing categories to manage asthma

|

Preschoolers (1 to 5 years) |

Children (6 to 11 years) |

Adolescents and adults (12 years and over) |

||||||

|

Corticosteroid (trade name) |

Low | Medium | Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High † |

|

Beclomethasone dipropionate HFA (QVAR) |

100 | 200 | ≤200 | 201–400 | >400 | ≤200 | 201–500 |

500 (maximum 800) |

|

Budesonide* (Pulmicort) |

n/a | n/a | ≤400 | 401–800 | >800 | ≤400 | 401–800 |

>800 (maximum 2400) |

|

Ciclesonide* (Alvesco) |

100 | 200 | ≤200 | 201–400 | >400 | ≤200 | 201–400 |

>400 (maximum 800) |

|

Fluticasone furoate* (Arnuity) |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 100 |

200 (maximum 200) |

|

|

Fluticasone propionate (Flovent, Aermony) |

<200 | 200–250 | ≤200 | 201–400 | >400 |

≤250 110 ‡ |

251–500 226 ‡ |

>500 (maximum 2000) 464 (maximum 464) ‡ |

|

Mometasone furoate* (Asthmanex) |

n/a | n/a | 100 | ≥200 to <400 | ≥400 | 100−200 | >200–400 | >400 (maximum 800) |

Notes: Dosing is in micrograms (mcg) and dosing categories are approximate, based on a combination of approximate dose equivalency and safety and efficacy data. Doses that are italicized and bolded are not approved for use in Canada, with the following exceptions: beclomethasone is approved for children ≥5 years of age; mometasone is approved for children ≥4 years of age. The maximum dose of fluticasone propionate is 200 mcg/day in children 1 to 4 years of age (250 mcg was included in this age group because the 125 mcg inhaler is often used to facilitate adherence and lower cost). Maximum dose of fluticasone propionate is 400 mcg/day in individuals 4 to 16 years of age.

* Licensed for once daily dosing in Canada, although a high daily dose may require a divided dose, administered twice daily.

† Maximum doses approved for use in Canada.

‡ Dosing for Aermony, which was added to the original table.

Source: Adapted from the Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS) Guideline on the management of very mild and mild asthma, by the kind permission of the CTS[3].

How are asthma control and risk of exacerbation assessed?

Asthma control is assessed by taking a careful history of symptoms and exacerbations and reviewing lung function in children able to do spirometry (typically 6 years of age and older) (Table 3).

Table 3. Well-controlled asthma criteria in preschoolers, children, and adolescents

| Characteristic | Frequency or value |

| Daytime symptoms | ≤2 days per week |

| Nighttime symptoms | <1 night per week and mild |

| Physical activity | Normal |

| Exacerbations | Mild and infrequent* |

| Absence from work or school due to asthma | None |

| Need for a reliever (SABA or bud/form)† | ≤2 doses per week |

| FEV1 or PEF | ≥90% of personal best |

| PEF diurnal variation | <10% to15% ‡ |

Bud/form Budesonide/formoterol; FEV1 Forced expiratory volume in 1 second; PEF Peak expiratory flow; SABA Short-acting beta-agonist

Note: A person who meets all criteria described above is considered to have well-controlled asthma.

* A mild exacerbation is defined as an increase in asthma symptoms from baseline that does not require systemic steroids, an emergency department (ED) visit, or hospitalization. “Infrequent” is not specifically defined, because the frequency of mild exacerbations that patients consider an impairment to quality of life can vary from person to person. When an individual feels that the frequency of mild exacerbations is impairing quality of life, their asthma should be considered poorly controlled. If a patient is having frequent mild exacerbations, they should be assessed to determine whether, at baseline, they have poorly controlled asthma.

† There are no established criteria for control when using bud/form as a reliever. However, reliever use often indicates that a patient is having symptoms: a criterion that can be objectively assessed.

‡ Diurnal variation is calculated as the highest peak expiratory flow (PEF) minus the lowest PEF, divided by the highest PEF flow multiplied by 100, for morning and night (determined over a 2-week period).

Source: Adapted from the Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS) guideline on the management of very mild and mild asthma, by kind permission of the CTS, using only relevant information for children [3].

Compared with previous guidelines, the criteria for daytime symptoms and need for a reliever has decreased from <4 times per week to ≤2 days per week. This change was made to better reflect the evidence for treatment in individuals with very mild and mild asthma. The definition of a mild exacerbation has also been clarified as one that “does not require systemic steroids, an emergency department (ED) visit, or a hospitalization”.

Recognizing that patients with well-controlled asthma can still be at higher risk of exacerbation, the 2021 CTS guideline recommends assessing the risk of exacerbation to inform treatment recommendations. This assessment is particularly important for individuals with very mild or mild asthma who are at higher risk of exacerbation, for any reason, and therefore should not be prescribed PRN SABA alone. Among other risk factors, young people considered at higher risk for exacerbation are those who: 1) Have any history of a previous severe asthma exacerbation (i.e., requiring use of systemic steroids, or an ED visit, or hospitalization); 2) Have poorly controlled asthma (as per Table 3) Over-use SABA (i.e., use more than two SABA inhalers over a 1-year period); or 4) Currently smoke. Passive exposure to smoke and the inhalation of other substances (e.g., vaping, cannabis) are also risk factors for asthma exacerbation, although the evidence base is not yet as strong as for current tobacco smoking. Individuals with any of these exposures should be individually assessed for risk of asthma exacerbations.

Treatment of very mild and mild asthma

The basis of asthma treatment continues to include: providing asthma education (which should include a written asthma action plan), identifying asthma triggers, and (when applicable) discussing environmental modifications.

What are the pharmacological treatment options in very mild asthma?

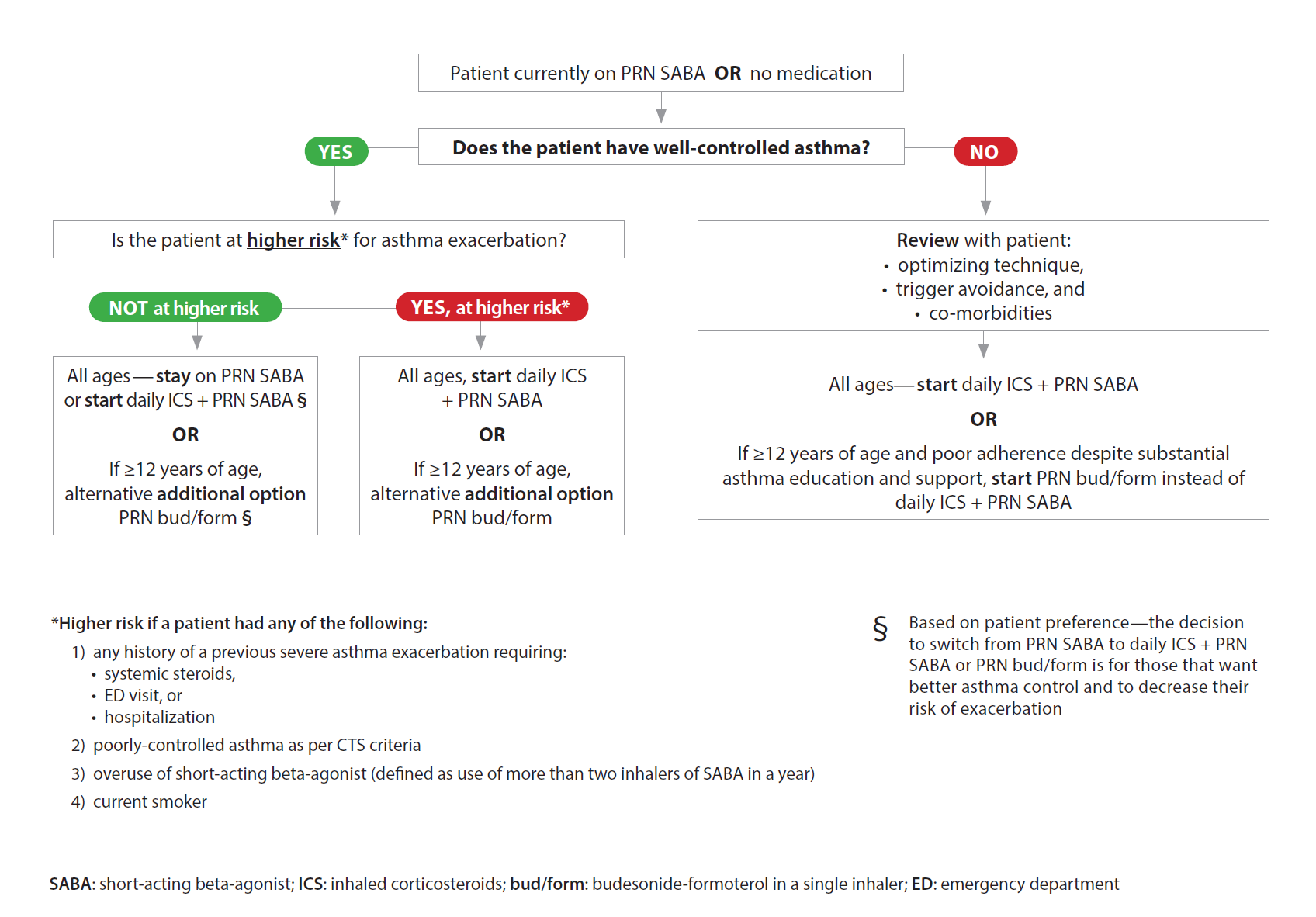

Figure 1 summarizes the treatment options, which are based on age, risk for exacerbation and, in some cases, personal preference.

Figure 1. Treatment approaches for very mild and mild asthma in preschoolers, children, and adolescents

Source: Reproduced from the Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS) guideline on the management of very mild and mild asthma, by kind permission of the CTS, using only relevant information for children[3].

Personal preference is a factor for young people with very mild asthma and a lower risk for exacerbation. Individuals of any age can continue with PRN SABA or switch to daily ICS + PRN SABA based on a moderate certainty of evidence that daily ICS + PRN SABA improve asthma control and decrease risk for exacerbation compared with PRN SABA alone. In this setting, however, the evidence of benefit—versus potential downsides (such as cost, treatment burden, and harms)—is less clear. There was a small decrease in growth rate in children aged 5 to 15 years who used ICS daily, though longer-term studies have suggested either no or low impact on growth (i.e., a maximum of a 1 to 2 cm decrease in final height). For individuals ≥12 years old with a lower exacerbation risk, PRN budesonide/formoterol is an option, with adult data showing decreased exacerbations and improved asthma control compared with PRN SABA alone, but less improved asthma control and inflammation than with daily ICS. PRN budesonide/formoterol is not recommended for children younger than 12 years old because it has not yet been studied in this age group.

Although PRN budesonide/formoterol is an option for some individuals, ICS are not approved for PRN use in Canada. The strategy recommended in other guidelines[5]—to take an ICS each time a SABA is taken—is not recommended by the CTS outside of harm mitigation strategies in adults ≥18 years old.

What are the pharmacological treatment options in mild asthma?

Daily ICS remain the first-line treatment for mild asthma (Figure 1), with ongoing evidence that mild asthma is better controlled with daily ICS and PRN SABA (versus PRN SABA alone), including in preschoolers.

As a second-line option to daily ICS, the CTS 2021 Asthma Guidelines still include a daily leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA) as an option for individuals of any age who cannot or will not use daily ICS. There is a risk of neuropsychiatric side effects, most commonly irritability, aggressiveness, anxiety, and sleep disturbance, reported in up to 16% of paediatric patients started on LTRAs.

For adolescents ≥12 years of age with mild asthma, the CTS guidance recognizes PRN budesonide/formoterol as a therapeutic option instead of low-dose daily ICS plus PRN SABA, but PRN budesonide/formoterol is the preferred option only for individuals with poor adherence to daily ICS despite substantial patient education and support.

Budesonide/formoterol is only available as a dry powder inhaler, and practitioners should ensure that the individual can use this device properly, which requires inhaling consistently, deeply, and forcefully to get the medication out of the device. The 200/6 mcg inhaler is approved for use as a PRN medication only for adolescents ≥12 years of age (1 puff PRN to a maximum of 6 puffs on one occasion, or 8 puffs per day). Practitioners should be aware that coverage through extended health care or provincial/territorial health plans is variable.

Should short courses of ICS be used for children with asthma?

The intermittent use of ICS at the onset of asthma symptoms, usually for 10 to 14 days, remains a common practice despite long-standing recommendations against this strategy[4]. Intermittent ICS use is appealing for a variety of reasons, including: (1) Ease of adherence, due to a symptom-driven (rather than daily) regimen; (2) The perception that a child without symptoms has no active disease; and (3) Apprehension about the side effects of ICS. Also, recent international guidelines recommending against the use of PRN SABA alone, and endorsing its use in combination with ICS use when PRN SABA is required, may have confused the issue of whether an intermittent or continuous ICS strategy is best in children with very mild or mild asthma.

Recent CTS guidelines do not recommend intermittent courses of ICS at onset of an acute loss of asthma control, compared with PRN SABA. Rather, they recommend daily ICS as the preferred strategy for most asthmatic children (Box 1). This strategy is based on consistent evidence for decreased exacerbations, better asthma control, and improved lung function of daily ICS compared with PRN SABA[1]. Evidence of benefit also includes more days with well-controlled asthma and less use of beta-agonists with the use of regular ICS, when compared with their intermittent use on an ‘as needed’ basis[4].

Controversy arose regarding intermittent use of ICS with 2020 recommendations from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). They endorsed short courses of PRN inhaled steroids in preschool children (e.g., in the form of nebulized budesonide) with onset of viral upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) symptoms if children are asymptomatic between wheezing episodes[5]. The studies that showed decreased exacerbations with short courses of ICS all used very high doses of inhaled steroids (e.g., 2 g of budesonide daily, 1500 mcg of fluticasone propionate daily). The frequency of URTI symptoms in preschoolers risks higher-than-necessary doses of ICS to achieve symptom control, thus increasing the risk for steroid-related adverse events. This approach is not recommended by the CTS.

To assist best practice, refer to the following:

- For providers: A summary of the CTS Asthma Guideline and a visual summary of asthma medication available in Canada, are available at the CTS website.

- For parents and patients: Asthma in children and youth, with frequently asked questions, can be downloaded for free from the CPS CaringforKids website.

- For patients aged 12 and older with mild asthma: A patient and family decision support tool, largely validated for adults, is available on the Electronic Asthma Management System.

Acknowledgements

This practice point has been reviewed by the Community Paediatrics and Drug Therapy Committees of the Canadian Paediatric Society and the CPS Allergy Section Executive, as well as by members of the Canadian Thoracic Society.

CANADIAN PAEDIATRIC SOCIETY RESPIRATORY HEALTH SECTION EXECUTIVE (2022)

Executive members: Estelle Chétrit MD (President-elect), Amy Glicksman MD (Secretary-treasurer), Connie Yang MD (Past-president), Zofia Zysman-Colman MD (President)

Principal authors: Connie Yang MSc MD, Zofia Zysman-Colman MD, Estelle Chétrit MDCM MBA, Anne Hicks MSc PhD MD, Joseph Reisman MD MBA, Amy Glicksman MD

References

- Yang CL, Hicks EA, Mitchell P, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society 2021 Guideline update: Diagnosis and management of asthma in preschoolers, children and adults. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med 2021;5(6):348-61. doi: 10.1080/24745332.2021.1945887. https://cts-sct.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Corrected-Ver_2021_CTS_CPG-DiagnosisManagement_Asthma.pdf (Accessed March 15, 2023).

- Ducharme FM, Dell SD, Radhakrishnan D, et al. Diagnosis and management of asthma in preschoolers: A Canadian Thoracic Society and Canadian Paediatric Society position paper. Can Respir J 2015;22(3):135-43. doi: 10.1080/24745332.2021.1877043. https://cps.ca/documents/position/asthma-in-preschoolers

- Yang CL, Hicks EA, Mitchell P, et al. 2021 Canadian Thoracic Society Guideline – A focused update on the management of very mild and mild asthma. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med 2021;5(4):205-45. doi: 10.1080/24745332.2021.1877043. https://cts-sct.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/FINAL-CTS_Very-Mild-and-Mild-Asthma-CPG.pdf (Accessed March 21, 2023).

- Lougheed MD, Leniere C, Ducharme FM, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society 2012 guideline update: Diagnosis and management of asthma in preschoolers, children and adults. Can Respir J 19(6): e81-e88. doi: 10.1155/2012/214129

- Cloutier MM, Baptist AP, Blake KV, et al. 2020 Focused Updates to the Asthma Management Guidelines: A Report from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee Expert Panel Working Group. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020;146(6):1217-70. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.10.003

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.