Practice point

Medical assessment of suspected traumatic head injury due to child maltreatment (THI-CM)

Posted: Jul 18, 2024

Principal author(s)

Michelle Shouldice MD, Michelle Ward MD, Kathleen Nolan MD, Emma Cory MD, Canadian Paediatric Society, Child and Youth Maltreatment Section

Abstract

Traumatic head injury due to child maltreatment (THI-CM) is a serious form of child abuse with significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in infants and young children. Health care providers have important roles to play, including identifying and treating these children, reporting concerns of child maltreatment to child welfare authorities, assessing for associated injuries and medical conditions, supporting children and their families, and communicating medical information clearly to families and other medical, child welfare, and legal professionals.

Symptoms associated with head trauma often overlap with those of other common childhood illnesses, and external signs of injury may be subtle or absent. As a result, THI-CM is frequently overlooked and its identification often delayed, leading to risk for ongoing injury. Assessing for head trauma in cases of possible child maltreatment includes considering medical causes for clinical findings and assessment for occult injuries. This practice point provides health care providers with guidance for identifying and medically assessing suspected THI-CM in infants and children.

Keywords: Abusive head trauma; Child abuse; Traumatic head injury due to child maltreatment (THI-CM)

Head injuries are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality due to child maltreatment[1]. These injuries result from forces applied directly to the head (impact, penetrating or crushing), inertial forces (shaking or whiplash), or a combination of both, and can include traumatic injuries to the skull, brain, and intracranial structures[2][3]. There may be accompanying injuries to the face, scalp, eye, neck, or spine. Limb and torso injuries may or may not also be present. Symptoms can range from subtle to severe and can, at times, be difficult to recognize.

Terminology

Traumatic head injury due to child maltreatment has been referred to by various terms, including ‘shaken baby syndrome’, ‘abusive head trauma’, ‘non-accidental head injury’, and ‘inflicted traumatic brain injury’. These terms are no longer recommended for use in Canada. The Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) recommend using the term ‘traumatic head injury due to child maltreatment’ (THI-CM). This practice point builds on PHAC’s 2020 Joint statement on Traumatic Head Injury due to Child Maltreatment (THI-CM): An update to the Joint Statement on Shaken Baby Syndrome[2], providing additional guidance relevant to health care providers.

Identifying traumatic head injury concerning for child maltreatment

Head injuries in infants and toddlers are often difficult to recognize based on symptoms and physical examination. Identification is particularly challenging when an infant has non-specific symptoms with no reported history of trauma[4]. Clinicians should consider the possibility of unreported head injury in infants and young children presenting with neurologic signs and symptoms (such as seizures, bulging fontanelle, altered consciousness), and in those with non-specific symptoms without a clear medical diagnosis (e.g., poor feeding, lethargy, vomiting, irritability, apnea, sudden collapse). The possibility of head injury should also be considered in infant siblings of children who have injuries concerning for maltreatment.

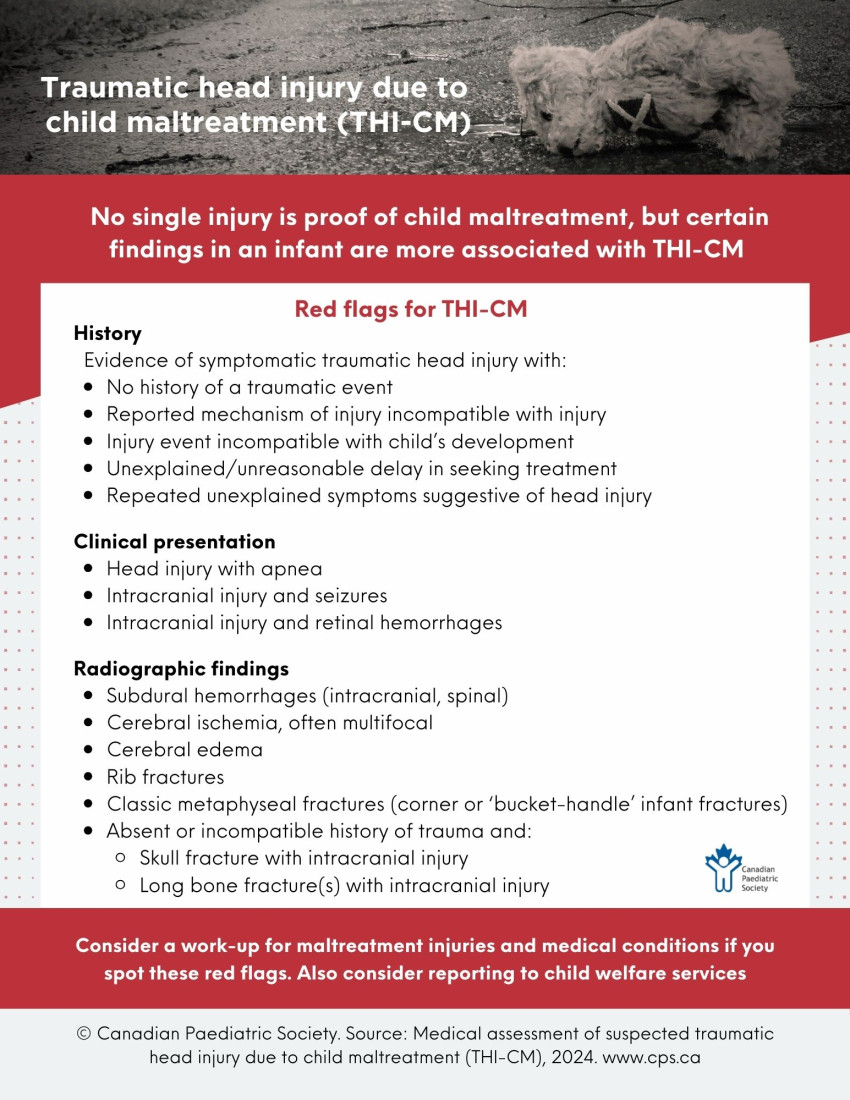

No single injury is pathognomonic for child maltreatment, but certain findings are more highly correlated with THI-CM than with other causes of head injuries. Such findings can be considered ‘red flags’ for possible THI-CM[5]-[7].

|

Table 1. ‘Red flags’ for traumatic head injury due to child maltreatment (THI-CM) |

|

History: Evidence of symptomatic traumatic head injury with:

Clinical presentation:

Radiographic findings:

|

|

Information drawn from references 5-7 |

The identification of subdural hemorrhage may be the impetus for considering child maltreatment. Trauma is the most common cause of subdural hemorrhage and this may result from birth, impact, or inertial forces (sudden deceleration, or acceleration/deceleration forces). When there is no clear accidental traumatic explanation, the most common cause of subdural hemorrhage is THI-CM[5][7]. However, it is important to consider a broad differential diagnosis to avoid missing other, rarer causes. Medical disorders such as coagulation abnormalities, inborn errors of metabolism (particularly glutaric aciduria type 1), and anatomic abnormalities (e.g., enlarged subarachnoid spaces, blood vessel malformations) are associated with subdural hemorrhages, though rarely[8].

Other findings that raise concern for child maltreatment, such as rib fractures or retinal hemorrhages, have a differential diagnosis that should be carefully considered[6][9].

Medical assessment of THI-CM

Approach

When concern for child maltreatment exists, clinicians should:

- Approach the case with an open mind, awareness of possible bias, and compassion for the child and family

- Manage the patient’s medical needs first, while also considering medico-legal steps

- Identify and document visible injuries and look for occult injuries using clinical assessment and testing

- Recognize that the differential diagnosis for injuries includes trauma, medical conditions, mimics of injury, or any combination of these

- Consider whether the injuries may have resulted from birth, medical interventions, the child’s actions, or the actions of another person (or a combination of these)

- Consider whether there are reasonable grounds to suspect child maltreatment and report to the local child welfare agency in accordance with provincial or territorial laws

- Take a multidisciplinary approach as early as possible, diagnose and document medical findings, and refrain from diagnosing abuse based on medical information alone

- Communicate with family and authorities as appropriate and document findings, opinions, and interactions clearly and objectively

- The clinical assessment and any information or opinions provided should stay within the individual clinician’s scope of expertise based on training and experience. Consult specialists as needed.

History

In cases of traumatic head injury and possible child maltreatment, taking a comprehensive paediatric history is essential. Details regarding onset and progress of symptoms, and the specifics of any injury-related event(s) reported are important for assessing etiology (medical or traumatic).

|

Table 2. Key points on history |

|

|

Symptoms of head injury

|

Irritability, fussiness Lethargy Poor feeding Vomiting Apnea, gasping, or irregular breathing Seizures Change in level of consciousness

|

|

Other pertinent findings |

Bleeding or bruising |

|

Detailed injury history |

Before event:

Circumstances leading to injury:

Following injury:

|

|

Developmental history

|

Gross motor milestones Plateau or regression |

|

Past medical history

|

Birth history (gestation, mode of delivery, instrumentation) Neonatal symptoms Sentinel injuries (i.e., medically mild previous injuries in infants that can precede severe inflicted injuries (e.g., bruising, intraoral injury, or bleeding)) |

|

Family history |

Bleeding abnormalities Neurodevelopmental abnormalities Inherited childhood conditions Consanguinity |

Physical examination

A detailed physical examination is essential and may indicate signs of a medical condition or trauma. However, in THI-CM the examination can be normal when a head injury is present[10]. Therefore, the physical examination cannot be solely relied upon to exclude the possibility of head injury.

Following acute assessment and resuscitation, a focused physical examination should include:

- Growth parameters, including head circumference, compared with previous measurements

- Head and scalp, noting status of anterior fontanelle

- Mouth, including the frenulae (tongue and lips)

- Neurologic examination

- Musculoskeletal examination

- Full skin examination, including ears, neck, chest, back, abdomen, buttocks, and genitalia[11].

Be especially vigilant for seizures, which are common in infants who have sustained a symptomatic head injury due to maltreatment. Often seizures may be electrographic with no obvious clinical correlate. A low threshold for early or continuous electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring is recommended for symptomatic infants, those with specific imaging findings, and those requiring critical care[12].

A dilated eye examination by an experienced paediatric ophthalmologist is indicated for infants and children with intracranial hemorrhage. Documentation should include the number, type, location, and extent of retinal hemorrhage and associated findings, such as retinoschisis (i.e., traumatic split in the layers of retinal tissue). This examination should be completed as soon as possible, ideally within 72 hours of injury because hemorrhages can resolve quickly. Where the technology is available, documentation using specialized retinal photographic equipment is recommended[13].

Laboratory evaluation

Laboratory testing can help assess for medical status and disorders that may be contributing to clinical findings.

Coagulation testing should include:[11][14]

- CBC, differential, blood smear

- International normalized ratio (INR), partial thromboplastin time (PTT)

- Fibrinogen

- Factor VIII, von Willebrand antigen, platelet-dependent von Willebrand activity

- Blood group (for interpretation of von Willebrand results)

- Factor IX, XIII

Metabolic testing should include:

- Review newborn screening results

- Consider urine organic acids and acylcarnitine profile

Screening for other injuries should include:

- Blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine

- Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), lipase (or amylase if lipase is unavailable)

Local factors (such as expertise, equipment, personnel, and pre-test probabilities) and clinical judgment may influence the medical evaluation, with additional testing based on clinical assessment (e.g., infection workup, metabolic testing, D-dimer) or the presence of other injuries[9][11][15].

Diagnostic imaging

Neuroimaging indications in suspected THI-CM include:

- Neurologic signs and symptoms, including unexplained macrocephaly or abnormal increase in head circumference

- Visible signs of head injury (bruising, scalp hematoma), particularly in infants

- History raising concern for head injury (e.g., reported shaking or impact, particularly in infants)

- Inadequately explained injuries, especially skull fracture, retinal hemorrhages, rib, or classic metaphyseal fractures, or bruising in pre-mobile infants[5].

Decision tools (e.g., the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN)) for head imaging have not been validated for child maltreatment. When head imaging is indicated for acute or symptomatic trauma, a computerized tomography (CT) scan is the test of choice[5]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an appropriate alternative in some non-acute cases and is frequently used as an adjunct to clarify or add information. A paediatric radiologist may advise regarding specific techniques for CT (3D skull reconstruction) and MRI (magnetic resonance angiography/magnetic resonance venography/ magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRA/MRV/MRS) to optimize imaging. Head ultrasound is not recommended as the sole imaging modality in THI-CM because of its reduced sensitivity for detecting hemorrhage and parenchymal injuries[8].

An MRI of a child’s full spine may identify additional injuries, particularly in cases where symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage is present or there is concern for neck injury, vertebral fractures, or multiple rib fractures.

A skeletal survey is indicated in cases of suspected physical abuse in children under 2 years of age and should include images of each body area as outlined in published protocols[16]. A “babygram” or bone scan (or both) are insufficient to detect occult fractures in this context. Bedside or portable X-ray machines are likewise insufficient for skeletal survey imaging. In critically injured children, the skeletal survey should be delayed until they are stable enough to have the imaging completed in the diagnostic imaging department. In most cases, the skeletal survey should be repeated approximately 14 days after the first imaging to identify acute injuries that may not have been visible on X-ray initially[16].

Abdominal imaging by CT is recommended for infants with an abnormal abdominal examination, abdominal bruising, or elevated transaminases or lipase or amylase[15].

Documentation

It is recommended that clinicians document the history and physical examination findings clearly, objectively, and in detail for cases of suspected maltreatment. Documentation should include specific findings (e.g., subdural hemorrhage, skull fracture, or cerebral edema), differential diagnoses considered, and diagnostic conclusions (e.g., traumatic head injury). Following diagnosis, a qualifying statement should be made that indicates the clinician’s concern for child maltreatment, including reasons.

Consultation

Consultation with a paediatric tertiary care centre is often appropriate to manage acute care needs or facilitate subspecialist involvement. A paediatrician specialized in child maltreatment can help guide clinical assessment and communication with family, health care professionals, child welfare, and law enforcement. Consultation with other specialists (e.g., critical care, ophthalmology, neurosurgery, neurology, orthopedics, endocrinology, hematology, genetics, rehabilitation) can assist as needed.

Clinicians must report concerns of child maltreatment to appropriate authorities and ensure that recommended medical evaluations in suspected THI-CM cases are completed. Health care providers who are unfamiliar with the medical literature and the legal implications of providing expert opinions in child maltreatment cases should be cautious about communicating a definitive medico-legal opinion regarding the likelihood of child maltreatment in suspected THI-CM cases. A paediatrician specializing in child maltreatment may be consulted to support communication of opinion in such cases.

Conclusion

Traumatic head injury due to child maltreatment (THI-CM) is a form of physical abuse with serious consequences. Because identifying THI-CM can be challenging, clinicians must be alert to possible signs, symptoms, and ‘red flags’. Assessment follows a standardized, objective process that considers medical and traumatic etiologies. Clinicians have an essential role in identifying and managing THI-CM, supporting families, and working with child welfare professionals.

|

Box 1. Key takeaways for assessing and managing traumatic head injury due to child maltreatment (THI-CM) |

|

Acknowledgements

This practice point aligns with the Joint Statement on Traumatic Head Injury due to Child Maltreatment 2020, with contributions by the Public Health Agency of Canada. It has been reviewed by the Acute Care, Adolescent Health, and Community Paediatrics Committees of the Canadian Paediatric Society, and by the CPS Hospital Paediatrics and Paediatric Emergency Medicine Sections.

CANADIAN PAEDIATRIC SOCIETY CHILD AND YOUTH MALTREATMENT SECTION EXECUTIVE (2020-2021)

Executive members: Emma Cory MD (Vice President), Natalie Forbes MD (Secretary-Treasurer), Clara Low-Décarie MD (Member-at-large), Robyn McLaughlin MD (Member-at-large), Amy Ornstein MD (Past President), Michelle Ward MD (President)

Principal authors: Michelle Shouldice MD, Michelle Ward MD, Kathleen Nolan MD, Emma Cory MD

Funding

There is no funding to declare.

Potential conflict of interest

All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed

References

- Bennett S, Ward M, Moreau K, et al. Head injury secondary to suspected child maltreatment: Results of a prospective Canadian national surveillance program. Child Abuse Negl 2011;35(11):930-6. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.05.018

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Joint statement on Traumatic Head Injury due to Child Maltreatment (THI-CM): An update to the Joint Statement on Shaken Baby Syndrome. February 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/childhood-adolescence/publications/joint-statement-traumatic-head-injury-child-maltreatment.html (Accessed May 15, 2024).

- Narang SK, Fingarson A, Lukefar J; American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Council on Child Abuse and Neglect. Abusive head trauma in infants and children. Pediatrics 2020;145(4):e20200203. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0203

- Jenny C, Hymel KP, Ritzen A, Reinert SE, Hay TC. Analysis of missed cases of abusive head trauma. JAMA 1999;281(7):621–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.621

- Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH). Child Protection Evidence: Systematic review; Head and Spinal Injuries. August 2019. https://childprotection.rcpch.ac.uk/child-protection-evidence/head-and-spinal-injuries-systematic-review/ (Accessed May 15, 2024).

- Maguire SA, Kemp AM, Lumb RC, Farewell DM. Estimating the probability of abusive head trauma: A pooled analysis. Pediatrics 2011;128(3):e550-64. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2949

- Piteau SJ, Ward MGK, Barrowman NJ, Plint AC. Clinical and radiographic characteristics associated with abusive and nonabusive head trauma: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2012;130(2):315-23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1545

- Choudhary AK, Servaes S, Slovis TL, et al. Consensus statement on abusive head trauma in infants and young children. Pediatr Radiol 2018;48(8):1048-65. doi: 10.1007/s00247-018-4149-1

- Chauvin-Kimoff L, Allard-Dansereau C, Colbourne M; Canadian Paediatric Society, Child and Youth Maltreatment Section. The medical assessment of fractures in suspected child maltreatment: Infants and young children with skeletal injury. Paediatr Child Health 2018;23(2):156-60. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxx131. https://cps.ca/en/documents/position/fractures-in-suspected-child-maltreatment

- Boehnke M, Mirsky D, Stence N, Stanley RM, Lindberg DM. Occult head injury is common in children with concern for physical abuse. Pediatr Radiol 2018;48:1123-9. doi: 10.1007/s00247-018-4128-6

- Ward MGK, Ornstein A, Niec A, Murray CL; Canadian Paediatric Society, Child and Youth Maltreatment Section. The medical assessment of bruising in suspected child maltreatment cases: A clinical perspective. Paediatr Child Health 2013;18(8):433-42.

- Greiner MV, Greiner HM, Caré MM, Owens D, Shapiro R, Holland K. Adding insult to injury: Nonconvulsive seizures in abusive head trauma. J Child Neurol 2015;30(13):1778-84. doi: 10.1177/0883073815580285

- Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH). Child Protection Evidence: Retinal Findings. 2020. https://childprotection.rcpch.ac.uk/child-protection-evidence/retinal-findings-systematic-review/ (Accessed July 12, 2024).

- Lindberg D, Makoroff K, Harper N, Laskey A, Bechtel K, Deye K, Shapiro R. Utility of hepatic transaminases to recognize abuse in children. Pediatrics 2009;124(2):509-16. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2348.A

- Anderst JD, Carpenter SL, Abshire TC, Killough E; AAP Section on Hematology/Oncology, the American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, et al. Evaluation for bleeding disorders in suspected child abuse. Pediatrics 2022;150(4):e2022049276. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-059276

- American College of Radiology – Society for Pediatric Radiology. Practice parameter for the performance and interpretation of skeletal surveys in children. Revised 2021. https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Practice-Parameters/Skeletal-Survey.pdf (Accessed May 16, 2024).

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.

Last updated: Dec 9, 2024

Click on the image to open it in larger window