Position statement

An update to the Greig Health Record: Preventive health care visits for children and adolescents aged 6 to 17 years – Technical report

Posted: Jun 6, 2016 | Reaffirmed: Mar 1, 2022

Principal author(s)

Anita Arya Greig, Evelyn Constantin, Claire MA LeBlanc, Bruno Riverin, Patricia Tak Sam Li, Carl Cummings; Canadian Paediatric Society, Community Paediatrics Committee

Executive Summary: Paediatr Child Health 2016;21(5):265-68.

What is in this update?

The Greig Health Record is an evidence-based clinical tool to be used in preventive care visits for school-aged children. It contains a checklist tool with supplementary information for reference and patient information handouts. This tool was designed using the model of the widely used Rourke Baby Record for infants and children from birth to age 5.[1] This is the first update of the Greig Health Record, which was first published in 2010.[2][3] It incorporates recent guidelines and research in preventive care for children and adolescents 6 to 17 years of age. The Greig Health Record comprises information and evidence which is relevant for all paediatric populations, although Canadian research and guidelines have been emphasized wherever possible. To access all aspects of the Greig Health Record, visit https://cps.ca/en/tools-outils/greig-health-record

Tables have been updated and additional tables and revisions can be found in the supplementary resource pages. As in the Rourke Baby Record, three fonts are used to reflect the strength of recommendations based on review of the literature: boldface for good, italics for fair and regular typeface for recommendations based on consensus or inconclusive evidence. Also following the format of the Rourke Baby Record, the classification system used here is based on the old classification system from the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC),[4] which evaluates the quality of supporting evidence in determining the strength of the recommendation.

The checklist tables are divided arbitrarily into early, middle and late age groupings, but it is important to remember that children develop at different rates and screening questions should be tailored to each individual. [5] For example, it may be appropriate to discuss pubertal development with some 8- or 9- year-olds, especially girls, but not appropriate for their less mature peers.

A small area for family history is included on the top left-hand corner of each checklist template to help identify children at risk for conditions such as mood disorders, cardiovascular disease and diabetes.[6][7] Other risk factors and allergies can also be recorded here.

Office counselling

Since the Greig Health Record was published in 2010, research into preventive care for this age group has been ongoing. Health care providers are ideally positioned to convey evidence-based recommendations at periodic health care visits and it is now well established that office counselling works for promoting helmet use, condom use to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs), more physical activity, responsible television viewing, and parental smoking cessation.[2][8] Office counselling may also be effective in increasing seat belt use.[9]

Visit frequency and structure

The frequency of preventive visits in this age group is recommended to be every one to two years (consensus).[2] However, 31% of adolescents in a 2011 Ontario survey reported no visits to a physician in the preceding year, including visits for acute issues.[10][11]

It is important to remember that the preventive health visit is not the only opportunity to address prevention. Not all elements in each section must be covered in every visit. Clinicians can use personal discretion when selecting topics to discuss with individual patients and the timing for specific discussions.

It is especially important to consider and counsel on special issues pertaining to the adolescent.[12] Review of the references on interviewing and examining adolescents may be useful,[13]-[15] and it is generally recommended that at least part of an adolescent’s visit be conducted in private, with parents or guardians excused. Confidentiality is central to a successful therapeutic relationship.[15][16] While there are variations among provinces and territories, minors can give informed consent to therapeutic medical treatment under Canadian common law provided they understand and appreciate the proposed treatment, the attendant risks and possible consequences.[13][16][17] It is also important to help adolescents understand both the scope and limits of patient confidentiality and explain that rules of confidentiality cannot cover cases of homicidal or suicidal ideation and emotional, physical or sexual abuse.[16][18]

Care of the adolescent involves a process of developing autonomy and responsibility for personal health care issues and transitioning from child-centred to adult-oriented health care. Both processes become particularly important when adolescents have special needs. The CPS provides a helpful statement for guidance in such cases.[19]

Template use

In the Greig Health Record, checklist templates are divided into three age ranges: 6 to 9, 10 to 13 and 14 to 17 years (inclusive). Section headings include: Weight, Height and BMI, Psychosocial history and Development, Nutrition, Education & Advice, Specific Concerns, Examination, Assessment, Immunization, and Medications. The checklist tables are divided arbitrarily into early, middle and late age groupings, but it is important to remember that children develop at different rates and screening questions should be tailored for each individual.[5]

A small area for family history has been included on the top left-hand corner of each template to help identify children at risk for conditions such as mood disorders, cardiovascular disease and diabetes.[6][7] Other risk factors and allergies can also be recorded here.

Note that for the physical examination section, consensus opinion supports the inclusion of height, weight, blood pressure and visual acuity screening. Other examinations are included for the purpose of case-finding, as needed, and can be used at the clinician’s discretion.

Five pages of selected guidelines and resources related to preventive care visits accompany the checklist tables. The first two pages focus on nutrition, sleep, safety and Internet resources and are designed to download, print and share with patients or parents.

Growth Charts

The WHO growth charts, adapted for Canada and released in 2010 by the Dieticians of Canada, Canadian Paediatric Society, Canadian Pediatric Endocrine Group, College of Family Physicians of Canada and Community Health Nurses of Canada, were redesigned in 2014. The new charts are available in black and white to facilitate facsimile transmission, with a blue icon for ‘Boys’ and a pink one for ‘Girls’.

The 0.1 percentile was removed from all charts in 2014 due to concerns that practitioners might mistakenly think that children whose growth fell between the 0.1 and 3rd percentiles were in the ‘normal’ range. Similarly, the 99.9 percentile was changed as a cut-off for severe obesity in BMI curves for 5- to 19-year-olds; it is now a dashed line to alert practitioners that if a child’s BMI is between the 97th and 99.9th percentiles (or beyond 99.9th), further assessment, referral or intervention is recommended.

Monitoring weight-for-age alone after 10 years of age is not recommended. Instead, BMI should be used to assess weight relative to height. However, percentile curves have been extended beyond age 10 for practitioners who wish to continue monitoring weight-for-age past age 10. The curves are dashed lines and a cautionary note is provided at the bottom: “WHO recommends BMI as the best measure after age 10”. The website at www.whogrowthcharts.ca includes BMI tables, links to BMI calculators and other important resources. A BMI between the 85th and 97th percentiles is defined as overweight and above the 97th percentile as obese.[20] See the section on Obesity, below.

Psychosocial History and Development

Social history-taking in younger children should focus on family structure and dynamics (including discipline), school performance and enjoyment, extracurricular activities and peer relationships with attention to bullying. Discussions shift as the child matures and are tailored to the age and maturity of the child as well as considering anticipated changes. It is important to discuss the changing nature of the adolescent’s relationships with peers and family and to inquire about school, work and social groups. The HEADSSS (Home, Education and Employment, Activities, Drugs, Drinking and Dieting, Sexuality, Suicide and Depression, Safety/Violence and Abuse) questionnaire is a guide for psychosocial interview for adolescents and is included in the supplementary resource pages for easy reference.[13]

Poverty

In Canada, nearly one child in seven lives in poverty.[21] The condition of low-income is more prevalent in families who are immigrant, racialized, Aboriginal, headed by a lone female parent, or raising a disabled child. Poverty has significant health effects on children and youth. Low socio-economic status is associated with higher rates of infant mortality, childhood asthma, overweight and obesity, injuries and deaths from injury, and mental health issues, including learning and emotional disorders. Children growing up in low-income families experience poorer adult health including physical disability, clinical depression and premature death.[22][23] While government subsidies are available to help alleviate poverty, many families are unaware of benefits that may be available to them by applying directly or by filing their taxes and claiming deductions and credits. Targeted resources are available in English at www.canadabenefits.gc.ca and in French at http://www.prestationsducanada.gc.ca/canben/. Even families who are unemployed can file a tax return for these benefits.

Peer relationships – Bullying

When asking about peer relationships, a clinician should also ask about negative experiences, including bullying. Bullying is defined as: “a form of aggression in which one or more children repeatedly and intentionally intimidate, harass, or physically harm a victim who is perceived as unable to defend herself or himself.”[24] It includes physical and verbal aggression. Bullying also includes more subtle, relational aggression that uses manipulations of relationships and reputations to harm another child.[25] Technology-assisted bullying is known as cyberbullying. Victims of bullying are at higher risk for self-harm even before adolescence and may suffer long-term sequelae into adulthood.[24][26] Bullies themselves are more likely to be incarcerated, unemployed or have dysfunctional long-term relationships later in life.[26] Parenting initiatives such as cognitive stimulation and emotional support are effective measures for primary prevention of bullying.[24] Cognitive stimulation and attending to early cognitive deficits such as language problems, imperfect causal understanding and poor inhibitory control are helpful strategies, possibly because children with these deficits also have decreased competence with peers (which can, in time, lead to them to exhibit bullying behaviours). Certain parenting styles are associated with bullying.[27] Health care providers can promote improving parenting skills. The American Academy of Pediatrics has a bullying handout and other information which can be shared with parents and patients.[28][29]

Mental health

Adolescence is a time of emotional changes, peer pressures and risks for substance abuse, depression, anxiety and suicide. Anticipatory guidance should be given to pre-adolescent as well as older children. Most health guideline-producing organizations recommend asking about emotional health.[6][30]-[33] The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening for major depressive disorder (MDD) in adolescents (Grade B recommendation) provided that systems for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up are also in place. For pre-adolescent children (age 7 to 11 years) there is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation.[32] As depressive disorders are present in 1% to 2% of children in this age group, health care providers should be aware of associated symptoms and behavioural issues.[6]

Depression is common in children and adolescents and is associated with significant negative impact.

In a 2011 Ontario survey of students in grades 7 to 12, 34% reported feeling elevated psychological distress (depression, anxiety, social dysfunction) in the preceding 12 months, with serious suicidal ideation in 10%, and 3% reporting a history of suicide attempt. This study showed a notable overlap among alcohol, drug use and mental health problems, with 9% of students reporting hazardous or harmful drinking combined with symptoms of anxiety or depression.[10][11] While the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) has raised concern in the past regarding suicidal ideation and suicidal risk, they are now recommended for children and adolescents with MDD and anxiety as the benefits appear to outweigh the risks. Evaluation and close monitoring for adverse effects and suicidal ideation and behaviours are still required.[34][35]

A recent Cochrane review offers some evidence of success of psychological and educational interventions for the prevention of the onset of depression in children and adolescents aged 5 to 19.[36] With limited evidence on which to base recommendations for treatment, primary prevention is of crucial importance.[37] Another review identifies modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors in children, along with some successful prevention strategies for anxiety disorders, eating disorders, substance abuse, disruptive behaviours and suicide. These treatment approaches have been especially effective in children and youth known to be at-risk because of parental mental illness or their own conditions, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or early-onset schizophrenia.[38] However, the USPSTF reports limited ability to detect suicide risk in adolescents and insufficient evidence to evaluate the risks and benefits of screening.[39][40]

Children’s Mental Health Ontario provides evidence-based resources and guidelines for health care professionals on topics from addiction and anxiety to self-harm and suicide prevention.[41]

Substances and Addictions

This heading in the record has been updated from Substance Abuse to Substances and Addictions. The section has been revised to recognize that harmful habits can include smoking, alcohol, drugs, gambling and excessive screen time associated with signs of addiction. Screen time can include use of the Internet, video gaming and smart phone use.

Gambling

Underage gambling can start in children as young as 9 or 10 years of age. In one recent Canadian survey, most adolescents reported that they have gambled at least once. Adolescents are two to four times more likely to have gambling problems than adults. Adolescent tendencies for risky behaviours can make them more vulnerable to developing a gambling problem. Depression, loss, abuse, impulsivity, antisocial traits and learning disabilities also increase the risk as well. Health care providers are recommended to screen for problem gambling as well as for depression and suicide risk in adolescents with a gambling problem. They should ask about frequency, a tendency to gamble more than planned, and behaviours suggesting they may be hiding gambling behaviours. Problem gambling is treated in the same way as other behavioural addictions.[42] The DSM-5 includes gambling disorder in its own category in the chapter on behavioural addictions.[43]

Gaming and the Internet

Youth are spending many hours per day gaming. Youth with addictive features of use show evidence of poor emotional and behavioural functioning. Correlated mental health problems include low self-esteem, social phobia and depressive symptoms.[44][45] The DSM-5 defines ‘dependence’ as having three or more of the following features:

- Tolerance

- Salience

- Withdrawal symptoms

- Difficulty controlling use

- Continued use despite negative consequences

- Neglecting other activities

- Desire to cut down [43][46]

Twelve percent of Ontario students reported symptoms of a gaming problem.[10][11]

Smoking

A review of recent evidence supports primary care-relevant behavioural interventions to prevent smoking in children and adolescents.[47]-[49] One meta-analysis showed a 19% risk reduction for smoking initiation. However, there was no effect on smoking cessation using either behavioural approaches or treatment with bupropion.[47] Incentive programs to prevent smoking initiation do not appear to work.[50]

While e-cigarettes containing nicotine are not approved for use or sale in Canada, some are sold with nicotine-free cartridges that may be replaced with nicotine-containing cartridges. Some products labeled ‘nicotine-free’ have been found to contain nicotine. Nicotine is highly addictive and flavoured cartridges may be particularly appealing to children and adolescents. The effect of inhaled contaminants and toxins is unknown.[51] A CPS position statement provides a comprehensive review of e-cigarettes and related concerns.[52]

Alcohol and Drugs

Early alcohol use can affect brain development and is associated with alcohol-related problems later in life.[53] The USPSTF reports insufficient evidence to support screening for alcohol problems and insufficient evidence for primary care behavioural interventions to prevent or reduce the abuse of prescription or non-prescription drugs by children and adolescents.[54][55] Nevertheless, a consensus recommendation to screen is included in the Greig Health Record based on the significant prevalence of problem drinking in Canadian youth and the possible effectiveness of education programs in changing youth perceptions of drug-impaired driving.[56][57] The CRAFFT screening questionnaire is highly sensitive for alcohol and drug problems in adolescents and young adults under 21 years of age and is included in the Greig Health Record.[58]-[60]

Note that prescription medications such as opioids and stimulants may also be abused.[61]

Caffeine

Physicians may not be accustomed to asking children and youth about caffeine use and the use of energy drinks. The consumption of caffeinated energy drinks is problematic in youth who commonly combine them with alcohol and are more sensitive to their effects, especially if they are non-habitual users.[62][63]

Health Canada recommends limiting ingestion of caffeine in children to the following:

- 45 mg/day for 4- to 6-year-olds

- 62.5 mg/day for 7- to 9-year-olds

- 85 mg/day for 10- to 12-year-olds

There is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation for teens but adults are recommended to limit ingestion to less than 400 mg/day. One can of cola contains up to 50 mg of caffeine; a cup of coffee 118 to 179 mg.[64] There is concern about the marketing of energy drinks targeted specifically to teens. Although Health Canada has set limits on the amount of caffeine to 180 mg per serving, products with higher levels may still be available.[65][66]

Body Changes

Physical changes of puberty should be addressed and anticipatory guidance offered. Assessment of sexual maturity is included in the physical examination. For easy reference, Sexual Maturity Rating (SMR) tables are included on the health record. Although age ranges have been included, it is recognized that there is considerable normal variation outside of the ranges provided.[67]-[69] Precocious puberty refers to the appearance of physical signs of puberty before the age of 9 years in boys and in girls before age 7 or 8 years. It is proposed by some that in certain ethnic groups, breasts and pubic hair may be normal as early as 6 years of age,[70] although there is considerable debate and concern about missing significant pathology.[71] Girls who have both breasts and pubic hair development at 7 or 8 years of age should preferably have their growth and history reviewed and a bone age evaluation for height prediction. These measurements should help identify children in need of further testing.[72]

Sexual Health and Relationships

The ‘Sexual Health’ heading on the Greig Health Record has been updated to ‘Sexual Health and Relationships’. Sexual health in the adolescent includes many factors that influence sexual development (both physical and psychosocial), sexual function and reproductive health. These topics must be addressed with sensitivity. Discussions can range from contraception to sexual orientation, from dating safety and abusive relationships to sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Sexual health counselling

The USPSTF recommends intensive behavioural counselling in sexually active adolescents to prevent STIs.[73] Safer sex counselling for risk reduction is recommended as there is good evidence that counselling for condom use in adolescents decreases the incidence of STIs.[74] A table of prevention counselling topics is included in the supplementary resource pages of the Greig Health Record. Strategies are recommended by the Public Health Agency of Canada [75] and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)[76] in their respective STI guidelines. Counselling about contraception and anticipatory counselling about folic acid supplementation are recommended by the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada for all females in their child-bearing years.[77][78]

Consent for sexual activity

In Canada, the criminal code defines the age of consent for sexual activity as 16 years for non-exploitative activity and as 18 years for situations involving prostitution, pornography or in relationships where there is a difference in authority or dependence. There are close-in-age exceptions. For 14- or 15- year-olds, the relationship must be non-exploitative and the partner must be <5 years older. For 12- and 13-year-olds, the partner must be <2 years older. For details, see: www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/other-autre/clp/faq.html.[79]

Sexting

Sexting is the sending or receiving of sexually explicit messages or images electronically. Youth, both male and female, report feeling pressured to send such messages. Young people need to be empowered to say ‘no’ to this new form of peer pressure. They also need to be made aware that such material can end up widely disseminated, have a permanent presence online, have unintended consequences for both sender and recipient and, finally, that the sender can be charged with possessing or sending child pornography – even if the images are of themselves.[80] Sexting may be an indicator of risks associated with sexual behaviour.[81]

Dating violence

The USPSTF reviewed intimate partner violence and concluded that screening women for intimate partner violence in their child-bearing years (14 to 46 years of age) is of moderate benefit.[82] In Canada, an estimated 43% of dating violence occurs to women 15 to 24 years of age. An estimated 13% of girls who have been in relationships have been physically abused and 54% of girls 15 to 19 years of age have experienced “sexual coercion” in a dating relationship.[83][84] Health care providers should always ask adolescent girls about their partners and the quality of their relationships.

Contraception

In Canada, emergency contraception is available in most regions without a prescription. It is available behind the counter in Saskatchewan and by pharmacist prescription in Quebec.[85][86] Emergency contraception is available free or at nominal cost through many health clinics, sexual health clinics, women’s clinics and emergency rooms across Canada.

Cervical screening guidelines

Updated cervical screening guidelines from the USPSTF, Cancer Care Ontario and the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada recommend screening every three years beginning at 21 years of age. Screening under age 21 years is not recommended “because abnormal test results are likely to be transient and to resolve on their own; in addition, resulting treatment may have an adverse effect on future child-bearing.”[87][88] The CTFPHC’s guidelines are slightly different. The CTFPHC recommends not screening women under 20 years of age. This recommendation is graded as strong with high quality evidence. It is interesting to note that they also recommend not screening for the group aged 20 to 24 years. This is a weak recommendation based on moderate quality evidence.[89]

Women who are not sexually active by 21 years of age are at lower risk; screening should be delayed screening until they become sexually active.[88]

None of these organizations recommend HPV screening for females under age 21 years of age. Vaccination against HPV does not eliminate the necessity for screening. Further research is needed into the effectiveness of HPV vaccines over the longer term.[90] For details on HPV vaccines, see Immunizations and TB Screening, below.

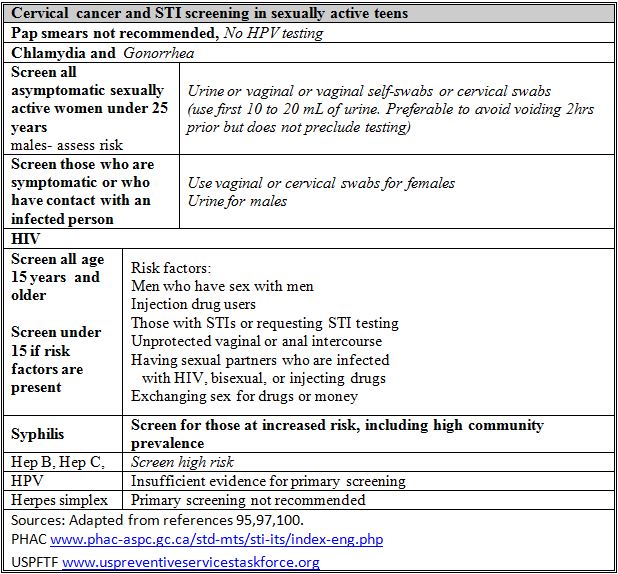

Sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening

STI testing is recommended in all sexually active women under 25 years of age, at least annually; there is good evidence for chlamydia and fair evidence for gonorrhea testing.[91] According to the USPSTF, there is insufficient evidence to recommend screening in males, but other guidelines suggest that males with risk factors should also be tested.[91][92]

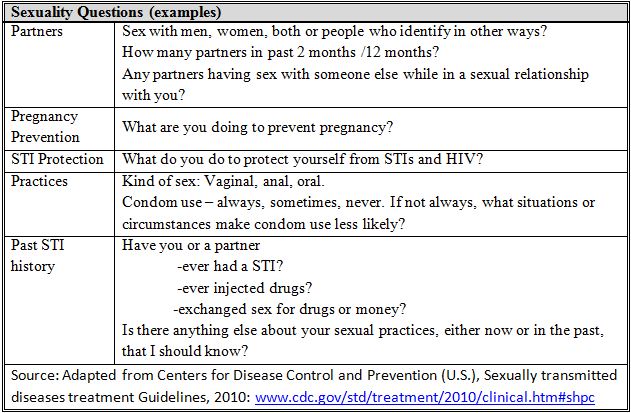

The CDC recommends asking about “the Five Ps”: Partners, Prevention of Pregnancy, Protection from STDs (sexually transmitted diseases), Practices and Past history of STDs.[93] A similar table has been included in the Greig Health Record, adapted with more inclusive language, Canadian terminology and condensed questions. Note that many adolescents believe that non-coital sexual contact is not ‘real sex’ and thus reduces their risk for infection.[94]

Urine samples are preferred for male chlamydia and gonorrheal testing. Urine testing is acceptable for screening asymptomatic women but has lower sensitivity than cervical or vaginal swabs (including vaginal self-swabs), especially for gonorrhea.[91][94]-[96] Females who are symptomatic or who have had contact with an infected person should be examined and cervical or vaginal swabs should be used. Symptomatic males should be examined and urine samples tested.[91][97][98] The CDC recommends self-administered vaginal swabs as the preferred method for sampling, especially in females who wish to avoid a genital examination.[94]

Note that for males who have sex with males, the CDC recommends gonorrhea screening for urethral, pharyngeal and rectal infections.[94]

HIV screening

The USPSTF has updated recommendations on screening for HIV. It recommends screening all sexually active adolescents aged 15 and older. Those under 15 years of age should be screened if they have risk factors, which include: men having sex with men, injection drug users, having an STI or requesting STI testing, engaging in unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse, having sexual partners who are HIV-infected, bisexual or injecting drugs, and engaging in sex for drugs or money. The net benefit of screening is substantial; treatment interventions now exist to reduce the risks for clinical progression, complications and death as well as for disease transmission.[99][100]

Pregnancy

Pregnant teens also require specific counselling and screening, the details of which are beyond the scope of this document. A summary of the evidence-based recommendations is available from the American Academy of Family Physicians.[101]-[103]

Breast and testicular routine or self-examination not recommended

Teaching breast self-examination or routine clinical breast examination to adults 40 to 70 years of age is not recommended. There is fair evidence of no benefit and good evidence of harm in the form of increased physician visits and benign biopsy results. For women under 40 years of age, there is little evidence on which to base a recommendation; however the very low incidence of breast cancer in this age group makes the net risk of harm more likely.[104][105]

There is evidence to recommend against counselling for testicular self-examination or routine clinical examination in individuals of average risk, in light of the low incidence of testicular cancer and favourable outcomes in the absence of screening.[106]

Menstrual issues

Dysmenorrhea is the most common gynecologic complaint among adolescent females,[107] and a leading cause of absenteeism from school and work in this age group.[108] Menstrual disorders, including dysfunctional uterine bleeding and amenorrhea, are significant health issues that adolescents are often reluctant to discuss with health care providers.[109] Menstruating adolescents should be screened for risk factors associated with iron deficiency.[110]

Nutrition

The importance of nutrition in the health of children is readily appreciated. Clear evidence exists for diet as a crucial causal factor in coronary artery disease and there is growing evidence that nutrition plays a key role in some cancers and in chronic diseases, such as hypertension and diabetes. Most clinicians recommend lowering intake of saturated fats and consuming ample amounts of fruits, vegetables, whole-grain cereals and legumes to reduce the risk of developing chronic diseases.[111]

Nutritional guideline tables have been added to the Greig Health Record’s reference pages to illustrate the relative proportions recommended for the four major food groups. They include information from Canada’s Food Guide,[112] Health Canada’s updated dietary reference intakes [113] and the National Academies (U.S.) Health and Medicine Division.[114] There is considerable debate about vitamin D requirements and supplementation.

Nutrition and puberty

Obesity is associated with earlier onset of menarche. The quality of nutrition may influence the timing of puberty by several months even in the absence of obesity. A review of observational studies shows a delay of puberty onset in young girls with higher intakes of vegetable protein and lower intakes of animal protein.[115]

Nutrition and anemia

In Canada, an estimated 3% of primary school-aged children are anemic. More are iron deficient. Iron deficiency has been associated with impaired cognitive and physical development. [116] The supplementary pages in the Greig Health Record include a table outlining who is at risk for iron deficiency and anemia. Ferritin is the recommended test for iron deficiency.

Supplements and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM)

Physicians should ask adolescents what vitamins, supplements and alternative health products and therapies they are taking. The WHO recommends taking supplements for specific nutrient deficiencies but suggests that healthy eating is effective for making sustainable corrections for dietary deficiencies over the longer term.[111]

Supplements used by adolescents may include performance-enhancing products such as DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone), creatine, protein supplements and anabolic steroids.[117]

The definition of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) adopted by the Cochrane Collaboration is: “a broad domain of healing resources that encompasses all health systems, modalities, and practices and their accompanying theories and beliefs, other than those intrinsic to the politically dominant health system of a particular society or culture in a given historical period”.[118] CAM can include herbs, homeopathic medicines, acupuncture, energy healing, yoga, special diets and biofeedback techniques.[117][119] Adolescents use herbs and dietary supplements more frequently than other forms of CAM.[117][120]

The rate of CAM use is approximately 20% to 40% in healthy children and more than 50% in children with chronic, recurrent or intractable health conditions. In certain subgroups, such as street-involved youth and adolescents who have suffered a relapse or other setback, CAM use rates approach 70%. [119][121]

Physicians need to be aware of, inquire directly about and promote open discussion regarding CAM use. Possible interactions with prescription medications make it especially important to inquire routinely about CAM use. As with conventional therapies, the safe use of CAM products in adults does not ensure the same result in children and adolescents.[119][122]

Body image/ dieting

Eating disorders, disordered eating and dieting can be addressed by inquiring about body image, self-esteem and an individual’s desire to change weight and the foods they eat. It is important to ask about weight control behaviours and obsessive thinking about food, weight, body shape or exercise.[123][124]

Health care providers should be aware that weight-related problems, including obesity, eating disorders and disordered eating, have risk and protective factors in common. Sensitivity to this information is important in the prevention of weight-related problems.[125]

Obesity

A strong recommendation for screening for obesity is made based on good evidence of the effectiveness of screening and of offering or referring individuals for intensive counselling and behavioural interventions.[126] The Greig Health Record includes tables of recommendations for overweight and obese children – see Supplementary page 5.

Obesity prevention

Canadian data from 2009 to 2011 give a prevalence of overweight (85th to 97th%ile) and obesity (>97th %ile) of 19.8% and 11.7% respectively in 5- to 17-year-olds. [127] Obesity in children and adolescents is associated with both physical health problems (mainly cardiovascular and metabolic) and psychosocial morbidity as well as increased mortality rates in adulthood. Populations at particular risk include low socio-economic groups, those living in rural or remote areas and certain ethnic groups, such as First Nations people living off reserve.[128]

Adolescence is a critical period in the development of obesity, as a time when diet changes, physical activity declines (especially in females) and sedentary behaviour increases. It is also a time of risk for depression and body image and self-esteem issues.[129]

One 2011 Cochrane review on interventions for preventing obesity in children found evidence to support the beneficial effects of obesity prevention programs in children aged 6 to 12. School-based strategies focusing on healthy eating, physical activity and body image showed promise.[130]

A number of systematic reviews have synthesized the evidence on the effects of interventions for obesity prevention in childhood. While there is some evidence of relationship between certain behaviours and obesity, it tends to be small and inconsistent due to the difficulties in measuring human behaviour.[131] Bosomworth has published a practical summary table showing some evidence-supported interventions for obesity prevention.[132] A modified version of this table is included in the supplementary resource pages.[131]-[58] Given the multifactorial etiologies of obesity, interventions to prevent or treat this condition should target all modifiable risk factors identified. The table below lists only a few strategies to prevent excessive weight gain in childhood.

Obesity treatment

Interventions based solely at home have low quality of evidence supporting them.[159] However, one systematic review of obesity interventions showed that parents’ participation improves body mass indices in their children and adolescents over time.[160] Interventions to treat obesity appear to be more effective when combined in more than one setting or environment.[161] As with prevention, interventions to treat obesity should also target all the modifiable risk factors identified and, optimally, may involve multidisciplinary teams (e.g., including a medical practitioner, psychologist, registered dietitian and exercise professional).

Obesity and diabetes

Diabetes screening recommendations have been updated in the supplementary pages of the Greig Health Record, in accordance with the 2013 Canadian Diabetes Association guidelines.[162]

Active Healthy Living

Physical activity and sedentary behaviour

Canadian guidelines recommend at least 60 minutes per day of moderate-to-intense physical activity for school-aged children and youth.[163] The 2012 report from Active Healthy Kids Canada found that 46% of children spend 3 or fewer hours per week in active play and 63% of their free time in sedentary activities. Their screen time average is 7 hours and 48 minutes per day. Yet, if given a choice, 92% of children said they would choose to play with friends over watching TV. Barriers to active play include competing forms of screen time and parental safety concerns.[164] Fewer than 20% of children meet the guideline’s recommendation of 2 hours or less per day of recreational screen time.[165] Counselling along with written information can modestly increase physical activity.[2] Handouts with physical activity tips are available from the Canadian Paediatric Society,[166] the Public Health Agency of Canada[167] and the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology.[163]

The benefits of increasing physical activity and reducing sedentary behaviour

There is good evidence that regular moderate-to-vigorous aerobic physical activity (PA) improves cardio-metabolic health.[168] PA may help to decrease overweight or obesity and improve blood pressure, serum lipids and glucose.[169] Vigorous PA provides further benefits for cardio-metabolic health.[169][170] There is good evidence to support that weight-bearing aerobic PA and strength training improve muscle and bone health.[169][171][172]

Based on good quality evidence, daily aerobic PA improves cognitive executive function and cognitive testing.[173] Based on moderate quality evidence, daily moderate-to-vigorous PA improves working memory, and daily vigorous exercise reduces depressive symptoms.[174][175]

Reducing inactivity improves fitness, body composition, body satisfaction in girls, and general self-esteem. Children who watch less than 3 hours per day of television show better pro-social behaviours.[176]

Physical activity and active video games

Active Healthy Kids Canada does not recommend using active video games as a strategy for increasing PA in children and youth. They do not lead to increases in overall daily PA levels. Nor do they offer the spectrum of benefits associated with outdoor play: fresh air, vitamin D, connection with nature and social interactions. Specific situations may exist where video games might improve motor skill development for specific populations or for rehabilitative purposes.[177]

Media health: TV, Internet use and hearing protection

In addition to counselling to reduce sedentary behaviours, educating families and individuals on their exposure to and use of television and electronic devices is strongly recommended.

Physicians make a positive impact on children’s television viewing habits. There is a relationship between watching violent television programs and violent behaviour and between excessive television watching and obesity. Also, watching certain programs may encourage irresponsible sexual behaviours. Children often have access to the Internet both at home and in school. Parents and children need to know the basic rules for safer Internet use.[178][179]

The periodic health visit is an ideal opportunity to talk with patients about protecting their hearing during especially loud activities (e.g., a rock concert) and by keeping the volume down on personal music devices. Permanent hearing loss is caused by loudness and length of exposure to noise. Rock concerts and personal music players can reach an intensity of 110 to 120 dB.[180][181] Using appropriately fitting earbuds and earphones is helpful.[182] The upper limit recommended for occupational noise exposure is 85 dB.[183]

Sleep Issues

School-aged children sleep 9 to 10 hours per day on average,[184] but the generally recommended normal sleep duration in this age group is 10 to 12 hours per day.[185][186] Between 4 and 6 years of age, children usually give up daytime naps. Though less commonly than in preschoolers, school-aged children can experience sleep problems, including bedtime resistance, significant sleep onset delay, nighttime fears and anxiety at bedtime.[185][187] Nightmares, night terrors and sleep-walking are common in this age group.[185]

Most adolescents sleep about 7 hours per day.[159] However, the recommended duration for adolescent sleep is 9 to 10 hours. The typical sleep pattern in adolescence is a delayed sleep phase through the week, which leads to ‘sleep debt’ and ‘catch-up’ sleep happening on weekends. Accumulation of sleep loss may have significant negative impact on daytime functioning, school and work performance, and quality of life.[184][187]

Sequelae of sleep deprivation

Getting inadequate sleep may be harmful. Insomnia is common, affecting an estimated 10% of U.S. adolescents and 6% of European adolescents. Chronic sleep loss in adults is associated with a greater risk of mortality.[188][189] There is fair evidence that short sleep duration over time is associated with subsequent weight gain and increased risk of concurrent and adult obesity.[190]-[95] The combination of short sleep duration and variable sleep patterns is associated with adverse metabolic outcomes, including increased risk of glucose intolerance and diabetes.[196] Short sleep duration and sleep problems have been shown to predict subsequent suicidal thoughts and attempts in teens.[197]-[199] Sleep disturbance is also associated with cardiovascular risk factors.[200]

Children with a bedtime routine, including reading, tend to sleep longer than those without a regular routine. Children with a late bedtime (after 9 pm) and those with a television in the bedroom generally sleep less and have a longer sleep latency.[201] Caffeine use may interfere with sleep onset and sleep quality. Longer sleep duration is associated with better cognitive performance, better working memory and memory consolidation, and fewer behavioural problems.[202][203] Improved sleep quality and sleep duration are associated with better school performance,[204][205] and there is fair evidence for improved teacher-rated alertness and emotional regulation.[206]

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a disorder of breathing during sleep. Common nighttime symptoms are snoring, mouth breathing and gasping during sleep and common daytime symptoms are fatigue, poor concentration and inattention. Etiologies of OSA are multifactorial. Hypertrophy of the adenoids and tonsils is the most common cause of OSA in the preschool years and continues to be an important etiology for school-aged children and adolescents. However, obesity has also become an important risk factor for OSA, particularly in school-aged children and adolescents. OSA prevalence is much higher in obese children than in non-obese children (13-66% vs. 1-3%, respectively). Sequelae of OSA and sleep deprivation include cardio-metabolic consequences, neurocognitive deficits (impaired learning and memory) and behavioural problems.[201][207]-[11]

Promoting sleep hygiene

Children should fall sleep independently.[201] Disruptive sleep practices, such as bed-sharing, are associated with more sleep problems, sleep anxiety, resistance and night-waking.[204] Physical activity during the day may improve sleep onset.[212] However, vigorous PA within 3 hours of bedtime may interfere with sleep onset. Media use and screen time should be avoided 1 to 2 hours before bedtime.[213]-[15]

Melatonin use in children

First-line treatment for sleep problems in children and adolescents is a behavioural or ‘sleep hygiene’ intervention, which involves optimizing personal sleep habits and the sleep environment. Pharmacological therapy should only be considered when behavioural intervention is unsuccessful and must be used with caution and with close monitoring. Research has shown that melatonin has some benefit when used for disorders of initiation and maintenance of sleep in otherwise healthy children and in individuals with neurodevelopmental disabilities. Melatonin use is “off-label” for treatment of sleep problems. More research is needed to help determine the impact and safety (especially long-term) of melatonin use in children and adolescents.[216]

Effective Discipline

Age-appropriate anticipatory guidance can be given to parents for discipline issues. It is important to emphasize that discipline includes providing encouragement for positive behaviours and clear, consistent communication of limits and rules. Parent handouts on this topic are available from the Canadian Paediatric Society.[217][218]

Injury Prevention and Safety

Clinicians should include safety topics in their discussions with patients and parents. A list of possible discussion topics is included on supplementary page 2 of the Greig Health Record, with links to the Canadian Paediatric Society, Parachute, and Canada Safety Council websites.[219]-[21]

Helmet safety

There is good evidence to support the use of bicycle helmets, with studies showing an overall decrease in the risk of head and brain injury of 65% to 88%.[222]-[24] Legislative interventions are also clearly effective in reducing head injuries, but only 8 of 13 Canadian provinces or territories have enacted bicycle helmet legislation.[225]-[28]

Vehicle safety

There is good evidence to support the use of booster seats for children between the ages of 5 and 7 and the use of seat belts for children aged 8 and older.[229]-[31] There is considerable variation in booster seat legislation in Canada. Some provinces or territories have laws requiring booster seat use until children are 8, 9 or even 10 years of age, while others have no age mandates.[232] Physicians should counsel parents on when it is safe to graduate children to seat belt use and especially to avoid premature graduation for smaller children.[230][233][234] Guidelines clarifying graduation by weight, height and age are available from Transport Canada,[235] Parachute[236] and the Canadian Paediatric Society.[237]

Driving safety should be discussed, particularly related to being in any motorized vehicle – including watercraft and snowmobiles – as a driver or passenger while under the influence of alcohol or drugs. [238]-[40] There is fair evidence for the negative effects of driving under the influence of marijuana.[241]

In contrast to driver education training programs, graduated licences appear to be effective in crash prevention.[242] One Cochrane review updates and confirms evidence for the effectiveness of graduated licensing in reducing motor vehicle crashes involving young drivers.[243]

The CPS and AAP both recommend restricting the operation of all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) and snowmobiles to persons 16 years of age or older. There is strong evidence to support that operators under 16 years of age are at significant risk of head and brain injuries as well as pelvic and spinal cord injuries. Physicians should also counsel parents that children should not ride as passengers on ATVs or snowmobiles.[244][245]

Trampoline safety

Trampolines are a high-risk source of injury. Data from the CHIRPP (Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program) database show that the majority of trampoline injuries occur in children 5 to 14 years of age. Upper limb fractures are the most common injury; however, severe injury can result from cervical spine trauma. Many trampoline injuries occur when there are multiple users on the jumping surface and there is inadequate or absent supervision. The CPS, AAP and Parachute recommend the elimination of all trampolines in the home environment and no participation for children younger than 6 years of age.[246]

Water safety

There is no clear evidence that swimming lessons prevent children from drowning or near-drowning and they should not be promoted as such. While there is insufficient evidence that swimming lessons and water safety education actually prevent injuries, there is evidence that swimming lessons improve swimming ability and water rescue skills.[247]-[49] Parental supervision and pool fencing are the two most effective strategies that prevent drowning and near-drowning; children and adolescents should be counselled to never to swim alone.[250]-[52] Swimming and swimming lessons can be encouraged and promoted to increase physical activity. Swimming skills are most efficiently learned beginning at about 5 years of age.[253]

Sun safety and tanning

The USPSTF has issued a guideline recommending that children and young adults 10 to 24 years of age, who are fair skinned, be counselled to minimize their exposure to ultraviolet radiation. This recommendation is based on fair evidence[254] and updates the 2003 guideline, which found no conclusive evidence of risk.

One Canadian Paediatric Society statement recommends that children and youth under 18 years of age be banned from commercial tanning facilities. Cutaneous malignant melanoma (CMM) accounts for approximately three-quarters of skin cancer deaths in Canada. Use of tanning beds increases with female gender and with age. An estimated 35% of 17-year-old North American females have used tanning beds. The link between having ever tanned indoors and an increased risk for developing CMM has been demonstrated, and early life exposure is associated with higher risks of CMM. An opiate-like addiction to tanning may be present in frequent tanners as melanin stimulating hormone is accompanied by the release of beta-endorphin.[255]

Firearms

In Canada, youth deaths from firearms are among the highest in the world: Canada ranks fifth among industrialized countries. Males 15 to 19 years of age are more likely to die from firearm-related injuries than from cancer, fires, falls and drowning combined. Suicides account for 79% of these deaths. Unintentional firearm injury rates are strongly correlated with home ownership of guns. If a gun is not present in the home, an adolescent contemplating suicide is more likely to use a less lethal method (with fewer completed suicides) or to not attempt suicide.

Physicians should routinely inquire about the presence of a firearm in the home and inform parents of the risks of ownership. One AAP statement makes the following strong recommendations: the most effective measure to prevent gun-related injuries is the elimination of firearms in homes and communities. Safer gun storage also reduces the risk of injury. Health care providers should counsel on the danger of allowing children to have access to guns and educate parents on how to limit access by unauthorized users.[256][257] Education of children about gun safety is not recommended as it may have the unintended effect of decreasing parental vigilance.[257]

Concussions

Sports such as football, rugby, hockey and soccer are associated with the greatest increase in risk for concussion. Females may be more susceptible to concussions than males,[258] and are at higher risk for concussions from playing soccer or basketball than their male peers. Younger age and a history of previous concussion increase the risk of prolonged post-concussion syndrome. Well-fitting helmets reduce but do not eliminate the risk of concussion in hockey and rugby. Soft head protectors are not helpful for preventing soccer- or basketball-related concussions. There is insufficient evidence to show that any intervention enhances recovery or diminishes long-term sequelae.[259] Thus, preventing concussions is key, including the following rules for play: no checks to the head in hockey, avoid head-to-head contact, wear appropriate head protection and maintain a respect for the brain – both your own and your opponent’s.[258] The Canadian Paediatric Society recommends that everyone involved in child and youth sport should be aware of the signs and symptoms of concussion.[260] A table is included in the second resources page of the Greig Health Record to share with sport participants, coaches, trainers and parents.

Concussion Resources

- Parachute: www.parachutecanada.org/thinkfirstcanada (info sheets and links to concussion assessment and recognition tools)

- Canadian Paediatric Society: www.cps.ca/documents/position/sport-related-concussion-evaluation-management (evaluation and management)

- Caring for Kids: www.caringforkids.cps.ca/handouts/sport_related_concussion parent/ coach handout

Skiing and snowboarding

The risk of injury for skiers and snowboarders is approximately 2 to 4 per 1000 participant days. The highest risk for injury is in children and adolescents 7 to 17 years of age, with the highest risk in snowboarders. Risk of injury is higher in beginners and in individuals using rented or borrowed equipment or on skis or snowboards with poorly adjusted bindings. Evidence supports the use of helmets to prevent injury while skiing or snowboarding. Data also suggest that helmets are not associated with an increased risk of neck injury. There is evidence to support using wrist guards while snowboarding.[261]

Hockey

Canadian data suggest that hockey injuries account for 8% to 11% of all adolescent sport-related injuries, with bodychecking accounting for the majority of these injuries. The fatality rate is double that caused by American football, while traumatic brain and catastrophic spinal cord injury rates are almost four times higher. Clinicians should advocate to eliminate bodychecking from recreational hockey and to delay bodychecking in leagues for male elite players. Girls’ and women’s leagues do not allow bodychecking, and players should continue to avoid bodychecking during play.[262]

Workplace safety

For adolescent workers, occupational injury and illness are largely preventable, and physicians can play a crucial role in prevention by alerting teens to common workplace dangers.[263] However, younger children may also be exposed to workplace hazards, especially in family businesses such as farm or fishing operations. It has also been shown that a workweek of 20 hours or more is associated with emotional distress in adolescents.[264]

Smoke detectors

Smoke detectors save lives. Families should be counselled to ensure that smoke alarms are properly installed and checked regularly. These alarms should be replaced every 10 years.[240] [265]-[66]

Environmental Hazards

Second-hand smoke

Second-hand smoke in children is associated with “asthma, altered respiratory function, infection, cardiovascular effects, behavior problems, sleep difficulties, increased cancer risk, and a higher likelihood of smoking initiation.”[267] Research is lacking on the effects of second-hand marijuana smoke, but similar effects may be present.[268] There is good evidence that brief counselling encourages smokers to attempt to quit.[48][49][269] Recent Canadian guidelines on smoking cessation strategies are available.[48][49][270]

One review of 18 trials where counselling was given to parents showed a significant increase in their smoking cessation rates. Parental quit rates averaged 23.1% in the intervention group and 18.4% in the control group. Such interventions had especially positive benefits when: children 4 to 17 years of age were present; the primary goal was smoking cessation; medication was offered as therapy; and there were high follow-up rates (>80%). Note that while these interventions were effective, most parents do not quit smoking; additional strategies are needed to protect children.[8][48][49]

Pesticides

A recent policy statement from the AAP summarizes evidence and concerns regarding pesticide exposure in children. It reviews classes of pesticides, sources of exposure, signs and symptoms of acute pesticide toxicity and the evidence for chronic effects of exposure, such as acute lymphocytic leukemia, brain tumors, lowered IQ, ADHD and autism. Strategies for preventing exposure and regulatory recommendations are also discussed.[271]

Prevention of disability from environmental hazards

Environmental exposures to lead, second-hand smoke and industrial pollutants are known to cause disability in children. One recent review of the evidence suggests that many disabilities of childhood have their roots in exposures to toxins, the stressors of poverty, and marketing practices that encourage unhealthy choices. Interventions to reduce or eliminate these exposures are described.[272]

Environmental Health Resources

- American Academy of Pediatrics: Pesticides & Herbicides Guidelines and Reviews: pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/130/6/e1757

- Canadian Partnership for Children’s Health and Environment / Physician &Patient Resources: www.healthyenvironmentforkids.ca/english/

- CDC National Center for Environment Health: www.cdc.gov/environmental/

- Commission for Environmental Cooperation: www.cec.org/children

Other safety topics

Traffic safety and safe road crossing, winter play and playground safety should be addressed with families of younger children.[220] Playground safety standards are regularly updated and can be purchased from the Canadian Standards Association (www.csagroup.org), and a wealth of information on a wide range of safety topics is available at no cost from Parachute (www.parachutecanada.org), the Canadian Safety Council (www.canadasafetycouncil.org) and the Canadian Paediatric Society (www.cps.ca; www.caringforkids.cps.ca). Where appropriate, farm and rural safety should also be discussed.

The risk of finding discarded needles, syringes and condoms in local environments such as the park and schoolyard should be raised with young families. The CPS has guidance for parents on how to educate children about and how to manage needle stick injuries.[273][274]

Preparing children for situations in which they need to show initiative can be part of counselling for young families. Young children can be asked if they know their own home phone number or address, or if they know what to do if they are lost, in danger, or home alone. Such anticipatory guidance is more important and helpful than the stock “never talk to strangers” rule.[275]

Abuse

Health care providers are recommended to maintain vigilance for signs or symptoms of abuse, maltreatment and neglect. Abuse may be physical, emotional or sexual. During primary school, children who experience abuse often have poor academic performance or concentration, show a lack of interest in school life, have difficulty forming or limited friendships or are frequently absent from school. Adolescents may suffer from depression, anxiety or social withdrawal. They may also run away from home or engage in risky behaviours such as substance use, early sexual activity, prostitution, street-involvement, gang activities or carrying guns.[276] Reporting suspected child abuse is mandatory in Canada.[277]

One recent USPSTF update comments on the evidence supporting clinic-based intervention for prevention of child abuse. While focusing on children 5 years and under, the review noted that: “Approaches applicable to children of all ages need to be developed, validated, and tested. The lack of studies assessing older children, identified in the previous USPSTF review as an important evidence gap, has yet to be addressed. Efforts to improve identification of children at risk for abuse and neglect need to be coupled with development and evaluation of effective interventions to which they can be referred once identified.”[278] As stated in the first Greig Health Record, vigilance for signs and symptoms of abuse continues to be recommended, despite the lack of studies. Besides being alert for signs and symptoms, educating children on what constitutes abuse and what they can do about it is also recommended.[2]

Dental Care and Fluoride

Professional dental care, including fluoride application and the selective use of sealants, has been clearly shown to reduce dental caries. Regular brushing with a fluoride-containing toothpaste and flossing are recommended for hygiene and aesthetics, reduction of gingival disease and cavity prevention.[279]-[81] Fluoride supplementation should be discussed in areas where fluoride is not present in sufficient amounts in the water supply.[282]

Specific Concerns

A section of the Greig Health Report is reserved for notation of specific concerns – such as an illness or personal issue raised during the visit or by examination – along with directions for where to find details elsewhere in the patient’s chart.

Physical Examination

Consensus opinion supports the inclusion of height, weight, blood pressure and visual acuity screening as part of the physical examination. Headings for other examinations have been included as reasonable for the purpose of case-finding.

Blood pressure

Blood pressure screening for primary prevention in asymptomatic children and adolescents received an “I” grading (insufficient evidence to make a recommendation) from the USPSTF. There is no clear association between screening and reduced risk for cardiovascular events and mortality in adulthood. This recommendation does not apply to children who have hypertension secondary to another condition, such as renal disease.[283]

The prevalence of hypertension in obese children and youth in the U.S. is estimated at 11%. The recommended first-line treatment for these individuals starts with lifestyle modification: weight reduction in children who are overweight or obese, increasing physical activity, reducing sodium,[284] engagement in health education and counselling.[285] Other guideline-producing agencies differ: the American Academy of Pediatrics, Bright Futures, the European Society of Hypertension and the American Heart Association all recommend routine screening. Like the USPSTF, the American Academy of Family Physicians states that there is insufficient evidence for screening.[286]

For present purposes, screening for hypertension is set in regular type-face to reflect a consensus-only recommendation on the Greig Health Record checklist. A link to tables showing blood pressure norms and percentiles is on supplementary page 5.

Visual Acuity Screening

Visual acuity in this age group should be assessed at each periodic health visit and whenever concerns occur.[287]

Scoliosis

Screening for idiopathic scoliosis in asymptomatic adolescents is not recommended by the USPSTF or the CTFPHC.[288] There is evidence that asymptomatic individuals have a mild clinical course and that interventions such as braces and exercise may not improve back pain or quality of life. Potential harms include unnecessary medical evaluations and psychological adverse effects, especially related to wearing corrective braces. The USPSTF states that clinicians should evaluate scoliosis when it presents as a symptom or is found incidentally.[289] The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and the American Academy of Pediatrics outline the evidence available but acknowledge that it does not definitively indicate for or against screening.[290][291]

Laboratory Investigations

Evidence does not support routine laboratory investigations.[289][292] Rubella immunity should be confirmed in sexually active females but laboratory screening is not necessary with documented evidence of prior rubella vaccination or immunity.[293]

A high index of suspicion should be maintained for iron deficiency in menstruating females. Children and youth with dietary, ethnic or other risk factors should be considered for screening. When screening for iron deficiency, ferritin – not hemoglobin – is the most sensitive and specific measurement.[111][294] It is important to remember that ferritin is an acute phase reactant that may be elevated in certain pathological states.

Sickle cell screening in at-risk populations is recommended for infants but insufficient evidence exists for recommending hemoglobinopathy screening in older children and adolescents.[289][295]

Lipid and plasma glucose screening should be performed in overweight or obese children over the age of 10.[296] Individuals with diabetes and/or familial dyslipidemias are also at increased risk, but evidence to make a recommendation is insufficient. Evidence for routine lipid or glucose screening is lacking.[297]

Immunizations and TB Screening

Immunization recommendations and reminders have been included as per the current Public Health Agency of Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) guidelines.[298] Vaccination schedules vary among provinces/territories. For this age group, the periodic health visit is a perfect opportunity to ensure that routine vaccinations are up-to-date and to discuss the need for other vaccines, including travel vaccination and new vaccines as they become available.

Pain reduction

An evidence-based practice guideline exists for reducing the pain of childhood vaccination. Minimizing pain with vaccinations in childhood may prevent the development of needle fears and vaccine avoidance later in life. Current recommendations and evidence are as follows: [299]

Immunizations – Varicella, MMR and MMRV

Two doses of varicella vaccine are now recommended to reduce the number of breakthrough cases, which may be related to waning immunity. Optimal spacing of the two doses is unknown. The second dose is commonly given at 18 months or at 4 to 6 years of age. The two doses must be given a minimum 3 months apart for children less than 12 years of age, and 4 weeks apart for older individuals. In vaccinated populations, the age for primary varicella may be increasing due to secondary vaccine failure. Since varicella severity is worse in adulthood and pregnant women are a particularly vulnerable population, prenatal assessment for varicella immunity is recommended. Because standard varicella serology does not detect antibodies to the vaccine strain, it is often not possible to determine whether an individual who received varicella vaccine is immune. Adequate evidence of immunity would be positive varicella serology (natural infection), two doses of vaccine, laboratory isolation of varicella or herpes zoster from a lesion, or previous diagnosis of varicella or herpes zoster by a health care provider. [300][301] Not all provinces/territories fund the second dose of varicella vaccine.

The NACI recommends two doses of measles and mumps vaccines. In Canada, the measles, mumps and rubella combination vaccine (MMR) is given, the first dose at 12 months and the second at 18 months or at 4 to 6 years of age.[302]

A combination vaccine of MMR and varicella is now available. The NACI states that MMRV may be used in place of individual MMR and varicella vaccines. The first dose is administered at 12 to 15 months of age and the second at 18 months or at 4 to 6 years of age. Catch-up for those not previously immunized consists of two doses of MMRV a minimum of six weeks apart, for children up to 12 years of age. Data is not available for adolescents.[302]

Meningococcal C

A dose of meningococcal conjugate vaccine is recommended in early adolescence even for those previously vaccinated as infants or toddlers. This is to ensure circulating antibodies are present during the peak risk years, from 15 to 24 years of age.[303]

A quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine may be preferred for the adolescent dose, depending on local epidemiology.[304] In the U.S., the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends routine vaccination with a quadrivalent vaccine for children 11 or 12 years of age, with a booster dose at 16 years.[305]

Meningococcal B

Currently, meningococcal B vaccination is not recommended for routine immunization programs. A NACI statement was issued in April 2014 for the new multicomponent meningococcal serogroup B vaccine. There is insufficient evidence to recommend this vaccine for routine immunization in Canada. Immunization is recommended for individuals at high risk for invasive meningococcal B disease (IMBD) due to chronic disease or close contact with a case of IMBD.[306]

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

HPV vaccine is now recommended for both genders, aged 9 to 26 years, for the prevention of infection caused by HPV. Of the three vaccines available in Canada, HPV-2 (covering types 16, 18) is recommended for females only, and HPV-4 (covering types 6, 11, 16, 18) and HPV-9 for females and males. HPV types 6 and 11 are associated with genital warts; HPV types 16 and 18 are associated with cancers of the cervix, penis, anus, mouth and oropharynx.[307][308] HPV-9 contains an additional 5 strains: 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58, which are also associated with malignancies. The U.S. CDC states that any of the three vaccines may be used, and that any may be used to complete the vaccination series (HPV-2 for females only).[309] The NACI has not yet issued recommendations for the HPV-9 vaccine, but with either HPV-2 (females only) or HPV-4, they recommend a two-dose regimen for individuals 9 to 14 years of age and a three-dose regimen for people ≥15 years of age.[310] School-based HPV immunization for boys is not funded uniformly in Canada.

Tuberculosis screening

Tuberculosis (TB) screening should be limited to high-risk groups. Although active TB is uncommon among Canadian-born children (except in the lndigenous population), recent immigrants are at higher risk.[311]

Supplementary Pages

Additional information in the updated Greig Health Record has expanded supplementary pages of guidelines and resources to five pages. The first page includes general information on growth, nutrition, physical activity, screen time, sleep and environmental resources. The second page has links to leading websites for clinicians and parents. The first two pages can be printed and distributed to parents and patients. The third page features resources for puberty and adolescent mental health issues, such as alcohol use, gambling, screen time, depression and suicide. The fourth page has the HEADSSS questionnaire and resources for the sexually active adolescent. The fifth page summarizes checklist information drawn from the 2010 and 2016 technical versions of the Greig Health Record, along with pain reduction strategies for vaccination. This last page also includes tables on obesity management and diabetes screening, with links to blood pressure tables.

To access all aspects of the Greig Health Record, visit www.cps.ca/tools-outils/greig-health-record

Endorsement: The College of Family Physicians of Canada endorses the Greig Health Record and its supporting literature.

Acknowledgements

This position statement was reviewed by the Adolescent Health, Infectious Diseases and Immunization, Injury Prevention, Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities, and Nutrition and Gastroenterology Committees of the Canadian Paediatric Society.

CPS COMMUNITY PAEDIATRICS COMMITTEE

Members: Carl Cummings MD (Chair), Umberto Cellupica MD (Board Representative), Sarah Gander MD, Alisa Lipson MD, Julia Orkin MD, Larry Pancer MD, Anne Rowen-Legg MD (past member)

Liaison: Krista Baerg MD, CPS Community Paediatrics Section

Principal authors: Anita Arya Greig MD, Evelyn Constantin MD, Claire LeBlanc MD, Bruno Riverin MD, Patricia Tak-Sam Li MD, Carl Cummings MD

References

- Rourke L, Leduc D, Rourke J. Rourke Baby Record: Evidence-based infant/child health maintenance guide: www.rourkebabyrecord.ca.

- Greig A, Constantin E, Carsley S, Cummings C; Canadian Paediatric Society, Community, Community Paediatrics Committee. Preventive health care visits for children and adolescents aged 6 to 17 years: The Greig Health Record – Technical report. March 2010.

- Greig A, Constantin E, Carsley S, Cummings C; Canadian Paediatric Society, Community, Community Paediatrics Committee. Greig Health Record – Executive summary. March 2010.

- Rourke L, Leduc D, Rourke J. Highlights of changes in the 2014 Rourke Baby Record: www.rourkebabyrecord.ca/updates.asp (Accessed October 28, 2015).

- Sacks D; CPS Adolescent Health Committee. Age limits and adolescents. Paediatr Child Health 2003;8(9);577.

- Zuckerbrot RA, Cheung AH, Jensen PS, Stein RE, Laraque D; GLAD-PC Steering Group. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): I. Identification, assessment, and initial management. Pediatrics 2007;120(5):e1299-312.

- Valdez R, Greenlund KJ, Khoury MJ, Yoon PW. Is family history a useful tool for detecting children at risk for diabetes and cardiovascular diseases? A public health perspective. Pediatrics 2007;120 Suppl 2:S78-86.

- Rosen LJ, Noach MB, Winickoff JP, Hovell MF. Parental smoking cessation to protect young children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2012;129(1):141-52.

- Ozer EM, Adams SH, Orell-Valente JK, et al. Does delivering preventive services in primary care reduce adolescent risky behavior? J Adolesc Health 2011;49(5):476-82.

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. The mental health and well-being of Ontario students, 1991-2013: www.camh.ca/en/research/news_and_publications/ontario-student-drug-use-and-health-survey/Pages/default.aspx (Accessed April 6, 2016)

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Drug use among Ontario students, 1977-2015: www.camh.ca/en/research/news_and_publications/ontario-student-drug-use-and-health-survey/Pages/default.aspx (Accessed April 6, 2016)

- Klein JD, Matos Auerbach M. Improving adolescent health outcomes. Minerva Pediatr 2002;54(1):25-39.

- Sacks D, Westwood M. An approach to interviewing adolescents. Paediatr Child Health 2003;8(9):554-6.

- Westwood M, Pinzon J. Adolescent male health. Paediatr Child Health 2008;13(1):31-6.

- Grant C, Elliott AS, Meglio G, Lane M, Norris M. What teenagers want: Tips on working with today’s youth. Paediatr Child Health 2008;13(1):15-8.

- Dibden L, Kaufman M. Confidentiality for adolescents in the patient/physician relationship. Paediatr Child Health 1997;2:19-20.

- Morton WJ, Westwood M. Informed consent in children and adolescents. Paediatr Child Health 1997;2:329-33.

- Harrison C; Canadian Paediatric Society, Bioethics Committee. Treatment decisions regarding infants, children and adolescents. Paediatr Child Health 2004;9(2):99-103.

- Kaufman M, Pinzon J; Canadian Paediatric Society, Adolescent Health Committee. Transition to adult care for youth with special health care needs. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(9):785-8: www.cps.ca/documents/position/transition-youth-special-needs,

- Dieticians of Canada. WHO Growth Charts adapted for Canada: www.whogrowthcharts.ca

- Campaign 2000. 2010 Report Card on Child and Family Poverty in Canada: http://www.campaign2000.ca/reportcards.html (Accessed May 16, 2016).

- Gupta RP, deWit ML, McKeown D. The impact of poverty on the current and future health status of children. Paeditr Child Health 2007;12(8):667-72.

- American Psychological Association. Effects of poverty, hunger and homelessness on children and youth. 2016://www.apa.org/pi/families/poverty.aspx

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Injury, Violence and Poison Prevention. Policy statement—Role of the pediatrician in youth violence prevention. Pediatrics 2009;124(1):393-402: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2009/06/11/peds.2009-0943.full.pdf+html

- Leff SS, Waasdorp TE. Effect of aggression and bullying on children and adolescents: Implications for prevention and intervention. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2013;15(3):343.

- Fischer HL, Moffitt TE, Houts RM, et al. Bullying victimisation and risk of self harm in early adolescence: Longitudinal cohort study. BMJ 2012;344:e2683.

- Zimmerman FJ, Glew GM, Christakis DA, et al. Early cognitive stimulation, emotional support, and television watching as predictors of subsequent bullying among grade-school children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159(4):384-8.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Bullying: It’s not OK: www.healthychildren.org/English/safety-prevention/at-play/Pages/Bullying-Its-Not-Ok.aspx

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Connected Kids: Safe Strong Secure: www2.aap.org/connectedkids.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. The Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. The Canadian Guide to Clinical Preventive Health Care. 1994.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Archive). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 2014: www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/guide/section3.html (Accessed May 17, 2016).

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and treatment for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Pediatrics 2009;123(4):1223-8.

- Steele MM, Doey T. Suicidal behaviour in children and adolescents. Part 2: Treatment and prevention. Can J Psychiatry 2007;52(6Suppl 1):35S-45S.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Antidepressant medications for children and adolescents: Information for parents and caregivers: www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/child-and-adolescent-mental-health/antidepressant-medications-for-children-and-adolescents-information-for-parents-and-caregivers.shtml (Accessed April 13, 2016).

- Korczak DJ; Canadian Paediatric Society, Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Committee. Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor medications for the treatment of child and adolescent mental illness. Paediatr Child Health 2013;18(9)487-91.

- Merry SN, Hetrick SE, Cox GR, Brudevold-Iversen T, Bir JJ, McDowell H. Psychological and educational interventions for preventing depression in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;12:CD003380.

- Cox GR, Callahan P, Churchill R, et al. Psychological therapies versus antidepressant medication, alone and in combination for depression in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;11:CD008324.

- Opler M, Sodhi D, Zaveri D, Madhusoodanan S. Primary psychiatric prevention in children and adolescents. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2010;22(4):220-34.

- O’Connor E, Gaynes BN, Burda BU, et al. Screening for and treatment of suicide risk relevant to primary care: A systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2013;158(1):741-54.