Position statement

Cultural safety in practice: Providing quality health care for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children and youth

Posted: Sep 18, 2025

Principal author(s)

Emilie Beaulieu MD, Sara Citron MD, Ryan Giroux MD, Cheyenne Laforme MD, Amber Miners MD, Brett Schrewe MDCM MA PhD, Elizabeth Sellers MD; Canadian Paediatric Society, First Nations, Inuit and Métis Health Committee

Abstract

In Canada, cultural safety in health care has emerged in response to the racism and systemic discrimination that Indigenous peoples often face when accessing care. Grounded in cultural humility, anti-racism, and trauma-informed care, cultural safety aims to ensure that Indigenous children and youth receive equitable, quality care. While understanding the principles of cultural safety is important, this statement focuses on applying these concepts in daily practice. Paediatric health care providers (HCPs) can pursue building a culturally safe practice by applying the ‘learn, self-reflect, and act’ framework. They should also consider the home environment, language, and cultural heritage of each child, youth, and family seen in practice, alongside the barriers to and facilitators of healthy living that Indigenous children and youth experience in Canada. Being mindful of health care system policies and practices—and how they affect patient care both locally and historically—is an important step toward offering culturally safe care in any practice setting.

Keywords: Anti-racism; Cultural humility; Cultural safety; Indigenous health; Trauma-informed care

Culture, language, and self-determination are pillars of health and well-being[1], and especially important for Indigenous Peoples whose lives have been disproportionately impacted by discriminatory policies and colonization. Negative legacy effects continue to shape the social determinants of health and health care systems in what is now called Canada, with persistent health inequities as the leading result[2]-[4]. First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples—referred to here collectively as Indigenous Peoples—have very different cultures but share historical and political legacies of oppression. That is why health-related services and coverage for some Indigenous Peoples differ from other groups in Canada[4][5].

Indigenous Peoples tend to share similarities in their worldviews that, because they are rarely reflected in traditional European or Western-centred health care systems and are not part of the standard curriculum in Canadian faculties of medicine, are not widely or well understood by health care providers (HCPs)[6][7]. Many Indigenous Peoples conceptualize health as a balance of physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual wellness, all of which influence their perception of disease and treatment. The conception of truth as multiple and shaped by individual experiences and storytelling, rather than as a single truth based on science, may create frictions between traditional and Western-based medicine. The concept of time as being cyclical and seasonal in nature rather than future-oriented may also cause frictions when accessing non-Indigenous-led services (e.g., scheduled appointments)[6][7]. To provide quality, culturally appropriate health care, Indigenous worldviews of truth and time must be reflected upon and intentionally integrated into clinical practice.

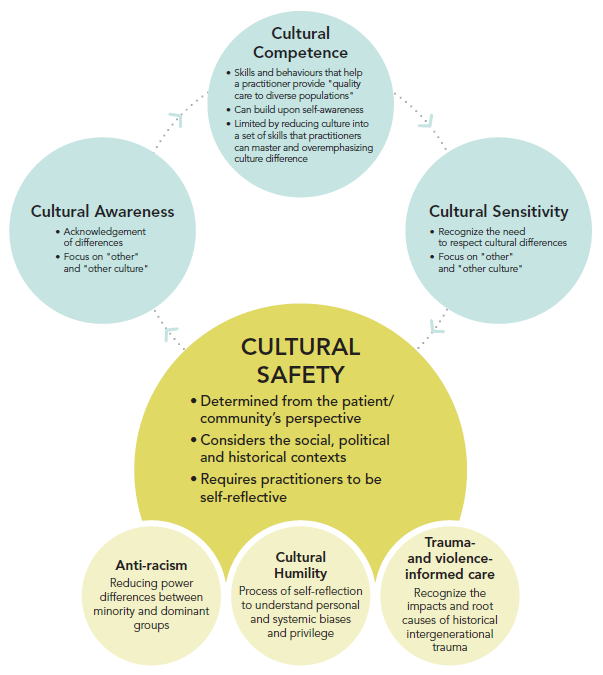

Cultural safety differs from related concepts—such as cultural awareness, cultural competence, and cultural sensitivity—because it integrates anti-racism and cultural humility (Figure 1)[8]. The Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) online module explores key concepts of culturally safe care in depth.

As a first step toward practising cultural safety, HCPs must recognize both their own personal and existing systematic biases, acknowledge their privilege, and work to address power imbalances through humble learning. Cultural humility includes acknowledging and providing space for Indigenous knowledges and traditional medicine in individualized, patient-centred care planning. Cultural safety, through trauma-informed care, acknowledges that interpersonal and environmental interactions can generate stress responses (e.g., fight, flight, freeze, or fawn) with strong historical roots in collective, intergenerational, and personal trauma[9]. Cultural safety hinges on patient and caregiver perspectives: only they can assess whether care interactions are culturally safe or not[8].

Figure 1. Continuum of cultural safety and humility

Source: Source: © All rights reserved. Common Definitions on Cultural Safety: Chief Public Health Officer: Health Professional Forum. Public Health Agency of Canada, 2023. Adapted and reproduced with permission from the Minister of Health, 2025. Available at: definitions-en2.pdf

Understanding the principles of cultural safety is important, but effective implementation in daily clinical practice is paramount. This statement offers a clinical approach to cultural safety for HCPs working with Indigenous children, youth, and families. Guidance includes reflection frameworks, tools, and recommendations intended to foster trusting clinical relationships and avoid triggering trauma. Culturally safe care is essential to optimizing future health outcomes for Indigenous children, youth, and families.

LEARN, SELF-REFLECT, ACT

This framework guides a three-step process of learning, self-reflection, and action to foster behaviour change(s)[10]. Individuals and institutions may be at different stages in this journey but are encouraged to continuously reassess positioning within this framework as new knowledge and experiences emerge.

| Text box: Learn, self-reflect, act: A provider’s journey toward culturally safe care |

|

1. Learn: Educate myself about the historical, social, and political contexts experienced by the Indigenous patients I serve, and how these contexts shape their health care access, experiences, and overall well-being. 2. Self-reflect: Examine my own culture and past experiences, along with my assumptions and biases, and consider how these may be affecting my interactions with patients. 3. Act: Bring this new knowledge and insight into my clinical work and relationships to make changes that improve patient care. |

As for any clinical encounter, HCPs must learn about the specific realities of each family and avoid assuming realities driven by the majority. Indigenous self-identification in health care, i.e., asking every patient whether they self-identify as Indigenous, with a view to improving their access to culturally relevant resources, is not implemented in most institutions in Canada. In the absence of this practice, HCPs should inquire respectfully about a child’s, youth’s, or family’s cultural and social setting.

First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples have unique contexts, some shared but many unshared depending on geographic, linguistic, and cultural setting. The specificities of each community and nation influence variable access to governmental services and programs. All these factors must be considered to provide culturally safe, quality care. There needs to be a thoughtful balance between asking enough questions and asking too many questions. The latter can be a significant burden for both patients and caregivers. Information about community settings and services can often be gathered beforehand by a health care team. Questions that could pose risk for re-traumatization should, if possible, be deferred until a trustful therapeutic relationship has been established. Clinicians in short-term care settings or high turnover environments, such as emergency departments or episodic care with medical trainees, should prioritize trust-building early, preferably from the start of an encounter. Explain the purpose of sensitive questions and establish secure, confidential methods for documenting sensitive information to minimize need for individuals or families to repeat their stories. HCPs must humbly avoid assumptions and remind themselves that hearing one part of a child’s story does not mean they understand the “full picture”.

Providers should be conscious that the following signs may indicate a patient’s or family’s culturally unsafe experiences in the past or present[11]:

- low utilization of available health and social services

- non-compliance with treatment plans

- denying suggestions of problems or issues

- reticence during interactions with practitioners, and reluctance to access care or meet with practitioners

- expressions of anger or low self-worth.

Triple H: Home, heritage, and healthy living

This section offers a culturally safe paediatric assessment, including questions and reflections organized into categories. The addition of ‘Home, Heritage, and Healthy Living’ (HHH) enhances the familiar SSHADESSS assessment (previous known as HEADSSS for adolescent histories)[12]. HHH information can be gathered and documented by any paediatric team member (including nurses and social workers) before or during a clinical encounter, even in time-constrained settings.

HOME

Asking about the home environment, community, and available services is an invaluable first step toward understanding Indigenous children, youth, and families (Table 1).

| Table 1. Learn and self-reflect: Home considerations | ||

| Learn | Self-reflect | |

| Community |

|

|

| Housing and connectivity |

|

|

| Health services |

|

|

ACT

To prepare for the clinical encounter, locate the family’s address or community on a map and assess the time, transportation, and cost required for them to reach your clinical location. Factor related barriers into follow-up planning, investigation schedules, and referrals. When providing care outside of the child’s community, consult with local health centres about services that could be provided closer to home. Ensure that medical consults, treatment plans, and prescriptions are transferred to local health centres, always providing for family consents. Contacting local health centre staff to inform them of any specialized care received and follow-up requirements is particularly helpful for patients with complex care needs. Ensure that children who require care outside their community have access to financial support for transportation and housing, either through Indigenous Service Canada, band councils, or Jordan’s Principle/Inuit Child First Initiative. Verify the child’s health insurance coverage and use the NIHB express scripts webpage to check that needed products and medication(s) are eligible for coverage[21].

When assessing housing, ask about the number of occupants, bedrooms, and possible impacts on health and well-being (e.g., asthma, chronic infections, intimate partner violence). Address specific concerns by linking families to resources like provincial/territorial Indigenous housing services and societies and Jordan’s Principle/Inuit Child First Initiative.

Clarify preferred (and available) options for contacting families (e.g., through extended family members or a local health centre, when needful) to schedule appointments or convey results, especially where communication options are limited. Consider telehealth or virtual care options to support in-person medical care, and do not penalize families for missed appointments associated with communication and transportation challenges.

HERITAGE

Cultural heritage encompasses worldviews, language, traditional ways of knowing, and family structures (Table 2).

| Table 2. Learn and self-reflect: Heritage considerations | ||

|

Learn |

Self-reflect |

|

|

Language |

|

|

|

Family structure |

|

|

ACT

Even when HCPs do not speak an Indigenous language, acknowledging linguistic differences by learning some key words can help promote cultural safety. Use interpreters to ensure that children, youth, and families are able to communicate in their preferred language. Introduce this option by asking “Do I need an interpreter?” rather than “Do you need an interpreter?” Be aware of scope for non-verbal cues toward understanding emotions “in the room” or intentions regarding care planning. For example, among Inuit peoples, a belief in non-interference and the value of personal independence can affect communication style. Direct requests may be perceived as rude and aggressive. An Inuit person may use a facial expression to convey information (e.g., raised eyebrows may indicate a “yes”)[28]. Allow time for and be comfortable with silence.

HCPs must also be mindful of the terms they use, which can carry strong cultural connotations or even be re-traumatizing[29]. For example, for some families with lived experience of residential schools, discussing academic requirements or the need for a child to attend school can suffice to re-traumatize. Try to consider the intergenerational trauma history that may be contributing to child or caregiver’s stress responses during a clinical encounter. If something said appears to have triggered a stressful or traumatic response, allow the individual or a family member to determine what is needed next. Support their decision to stop the encounter whenever it is safe to do so. Apologies for inadvertent triggering can go a long way.

Do not assume the adult accompanying a child or youth at a health visit is a biological parent or primary caregiver at home. Always clarify their relationship to the child with warm and welcoming questions. When an alternate caregiver accompanies the child and cannot provide needed information, explore options like phone calls or virtual services to engage primary caregivers. Deferring a management plan to a future appointment when the primary caregiver is present can delay care and impede trust-building. Delayed engagement can make family members even less likely to show up for the next appointment, especially if they have far to travel. Share your understanding of a family’s structure with colleagues to prevent misinterpretation of behaviours and situations that might lead to involving child welfare authorities. For example, single caregivers who are in hospital without their usual extended family and community support may believe that nurses are present to help share the care of children, and may therefore be comfortable with being away from children for a considerable period. Western views may perceive and interpret this hiatus as neglectful or inadequate parenting.

Be open to learning about traditional ways of knowing and healing. Family-directed goals of care should be elicited to guide treatment planning. Try to discuss how traditional practices might be integrated into health plans. Knowing what culturally appropriate resources and services are available locally is essential best practice, and inquiring whether local hospitals or clinics invite or offer participation from Elders, traditional healers, or Indigenous health consultants and navigators, as well as spaces for cultural practices like smudging and family visitations, is important.

HEALTHY LIVING

Diet and activities are influenced by the child’s context (Table 3).

| Table 3. Learn and self-reflect: Healthy living considerations | ||

| Learn | Self-reflect | |

| Activity |

|

|

| Food |

|

|

ACT

Discuss with families what is available in their environment to support healthy active living (e.g., recreation centres and extra-curricular activities)[32]. Use culturally appropriate tools (e.g., the Nunavut Food Guide[33], the Inuuqatigiit Centre for Inuit Children, Youth and Families developmental pamphlets[34], and the Qaujigiartiit Health Research Centre handbook[35]) and learn more about local issues, such as lack of clean drinking water and high food prices, to help co-plan goals that respond to each family’s needs. Adapt counselling toward healthy active living. Some Indigenous cultures prefer excess weight on children and may be more concerned about children being underweight. Recognize differences in food preferences and traditions, and advocate for culturally safe food for children hospitalized outside their community.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Applying the ‘learn, self-reflect, and act’ framework supports culturally safe paediatric practices, ensuring quality, equitable care for Indigenous children and youth.

Learn: Health care providers (HCPs) must recognize that understanding the social, cultural, and political contexts of Indigenous Peoples, including the impacts of colonial policies and systemic racism, is as essential to providing care as knowledge of specific medical conditions. This foundational awareness is crucial to addressing broader determinants of health for Indigenous children and youth. HCPs should engage with resources like the Canadian Paediatric Society’s cultural safety module, then pursue learning opportunities focused on local communities and ongoing contextual issues, especially when regularly caring for Indigenous children and youth.

Self-reflect: HCPs should regularly examine how their own beliefs, assumptions, and biases may be influencing the care they provide and their interactions with Indigenous patients and families. They should approach care with humility and curiosity, acknowledging and apologizing for any missteps while remaining open to feedback. Health care organizations must reflect on how to integrate Indigenous worldviews, create safe spaces for Indigenous patients, and ensure that Indigenous perspectives are respected, reflected, and valued.

Act: HCPs must consider each Indigenous family’s unique contexts, including home and cultural factors affecting healthy living. Offering flexible communication and appointment systems, creating healing spaces, and working with system navigators and traditional healers can enhance care significantly. Lasting cultural safety requires systemic and institutional changes, specifically recruiting and supporting Indigenous HCPs, traditional healers, and knowledge keepers. Enabling Indigenous self-identification processes, ensuring equitable access to supports like Jordan’s Principle and the Non-Insured Health Benefits program, and incorporating Indigenous art, language, and traditions to celebrate culture and foster healing, are important steps toward culturally safe care practice.

Advocating for policies, funding, and resources that respect Indigenous contexts is essential to creating an equitable health care system that ensures quality care for Indigenous children and youth.

Acknowledgements

This statement was reviewed by the Acute Care, Adolescent Health, Bioethics, and Community Paediatrics Committees of the Canadian Paediatric Society. While representatives from national First Nations, Inuit, and Métis organizations provided valuable guidance during its development, this statement does not necessarily reflect their views or those of the organizations they are affiliated with.

CANADIAN PAEDIATRIC SOCIETY FIRST NATIONS, INUIT AND MÉTIS HEALTH COMMITTEE (2024-2025)

Members: Emilie Beaulieu MD (Co-chair), Ryan Giroux MD (Co-chair), Amber Miners MD (Board Representative), Brett Schrewe MDCM MA PhD, Sara Citron MD, Elizabeth Sellers MD, Tanelle Smith MD

Liaisons: Jason Deen MD (American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Native American Child Health), Melanie Morningstar (Assembly of First Nations), Marilee Nowgesic (Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association), Laura Mitchell (Indigenous Services Canada), Stephanie Thevarajah (Métis National Council), Kristina Kopp (Métis National Council), Donna Atkinson (National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health)

Principal authors: Emilie Beaulieu MD, Sara Citron MD, Ryan Giroux MD, Cheyenne Laforme MD, Amber Miners MD, Brett Schrewe MDCM MA PhD, Elizabeth Sellers MD

Funding

There is no funding to declare.

Potential Conflict of Interest

Dr. Brett Schrewe reported a relationship with a for‐profit and/or a not‐for‐profit organization: RésoSanté Colombie-Britannique - membre, conseil d'administration. No other disclosures were reported.

References

- National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health. Culture and Language as Social Determinants of First Nations, Inuit and Métis Health. June 2016 (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- In Plain Sight: Addressing Indigenous-specific Racism and Discrimination in B.C. Health Care. Addressing Racism Review, Full Report November 2020 (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada. Addressing Racism in the Healthcare System: A Policy Position and Discussion Paper. April 2021 (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Allan B, Smylie J; Wellesley Institute. First Peoples, Second Class Treatment: The Role of Racism in the Health and Well-Being of Indigenous Peoples in Canada Executive Summary. 2015 (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Native Women’s Association of Canada. Fact Sheet: Non-Insured Health Benefits (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. Indigenous Worldviews vs Western Worldviews. January 26, 2016 (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Indigenous Health (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Government of Canada. Common Definitions on Cultural Safety: Chief Public Health Officer Health Professional Forum (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Graham S, Kamitsis I, Kennedy M, et al. A culturally responsive trauma-informed public health emergency framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in Australia, developed during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19(23):15626. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192315626

- National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health, Canadian Paediatric Society. Providing culturally safe care of Indigenous children and youth. October 2023.

- Early Childhood Development Intercultural Partnership, Ball J. Cultural Safety (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Coble C, Srivastav S, Glick A, Bradshaw C, Osman C. Teaching SSHADESS versus HEADSS to medical students: An association with improved communication skills and increased psychosocial factor assessments. Acad Pediatr 2023;23(1):209-15. doi: 10.1016/J.ACAP.2022.09.012

- Canada’s National Observer, Cimellaro M. Urban Indigenous populations continue to grow: 2021 census. September 22, 2022 (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Statistics Canada. A snapshot: Status First Nations people in Canada. April 20, 2021 (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Statistics Canada. Population growth in Canada’s rural areas, 2016 to 2021. February 9, 2022 (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Government of Canada. Inuit Nunangat Housing Strategy. April 29, 2019 (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Statistics Canada. Housing conditions among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit in Canada from the 2021 Census September 21, 2022 (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Government of Canada. Ending long-term drinking water advisories. Updated August 29, 2025 (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada. Connectivity in Rural and Remote Areas: Progress on access to high-speed Internet and mobile cellular services lags behind for rural and remote communities and First Nations reserves. Report 2. 2023 (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Schrewe B. Connected from coast to coast to coast: Toward equitable high-speed Internet access for all. Paediatr Child Health 2021;26(2):76-8. doi: 10.1093/PCH/PXAA129

- Express Scripts Canada. Welcome to the Non-Insured Health Benefits (NIHB) Program (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Building Brains Together, Halliwell C. Parenting from Western and Traditional Indigenous Perspectives (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- First Nations of Quebec and Labrador Health and Social Services Commission. Customary adoption and tutorship (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Metis National Council. Children and Family Services (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Canadian Geographic. Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada. Family Structures (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Best Start Resource Centre. A Sense of Belonging: Supporting Healthy Child Development in Aboriginal Families. 2011 (Accessed September 15, 2025).

- Ball J. Finding fitting solutions to assessment of Indigenous young children’s learning and development: Do it in a good way. Front Educ 2021;6:696847. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.696847

- Møller H. Culturally safe communication and the power of language in Arctic nursing. Inuit Studies 2016;40(1):85-104. doi: 10.7202/1040146ar

- University of British Columbia. First Nations and Indigenous Studies. Terminology (Accessed September 15, 2025).

- First Nation Health Authority. Traditional Food Fact Sheets (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Statistics Canada. Study: Food insecurity among Canadian families, 2022. November 14, 2023 (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health. Indigenous Peoples’ physical activity social determinants of health. March 30, 2023 (Accessed July 17, 2025).

- Inuusittiaringniq Living well together, Department of Health, Government of Nunavut. Nunavut Food Guide (Accessed September 10, 2025).

- Inuuqatigiit Centre for Inuit Children, Youth and Families. Child Development Pamphlets (Accessed September 10, 2025).

- Qaujigiartiit Health Research Centre (Accessed September 10, 2025).

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.