Position statement

Standards of diagnostic assessment for autism spectrum disorder

Posted: Oct 24, 2019

Principal author(s)

Jessica A. Brian, Lonnie Zwaigenbaum, Angie Ip; Canadian Paediatric Society, Autism Spectrum Disorder Guidelines Task Force

Paediatr Child Health 2019 24(7):444–451.

Abstract

The rising prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has created a need to expand ASD diagnostic capacity by community-based paediatricians and other primary care providers. Although evidence suggests that some children can be definitively diagnosed by 2 years of age, many are not diagnosed until 4 to 5 years of age. Most clinical guidelines recommend multidisciplinary team involvement in the ASD diagnostic process. Although a maximal wait time of 3 to 6 months has been recommended by three recent ASD guidelines, the time from referral to a team-based ASD diagnostic evaluation commonly takes more than a year in many Canadian communities. More paediatric health care providers should be trained to diagnose less complex cases of ASD. This statement provides community-based paediatric clinicians with recommendations, tools, and resources to perform or assist in the diagnostic evaluation of ASD. It also offers guidance on referral for a comprehensive needs assessment both for treatment and intervention planning, using a flexible, multilevel approach.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder; Diagnostic evaluation; Intervention planning

WHO SHOULD CONDUCT THE ASD DIAGNOSTIC ASSESSMENT?

In most provinces and territories, only physicians or psychologists are licensed to diagnose autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [1]. In some communities, appropriately trained nurse practitioners may also make this diagnosis. Emerging evidence suggests that a trained sole practitioner can diagnose less complex cases of ASD [1]–[4], yet most clinical guidance documents recommend a team-based approach, led by a primary care provider, paediatric specialist, or clinical child psychologist who is trained to diagnose ASD [1][3]–[15].

THREE APPROACHES TOWARD AN ASD DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

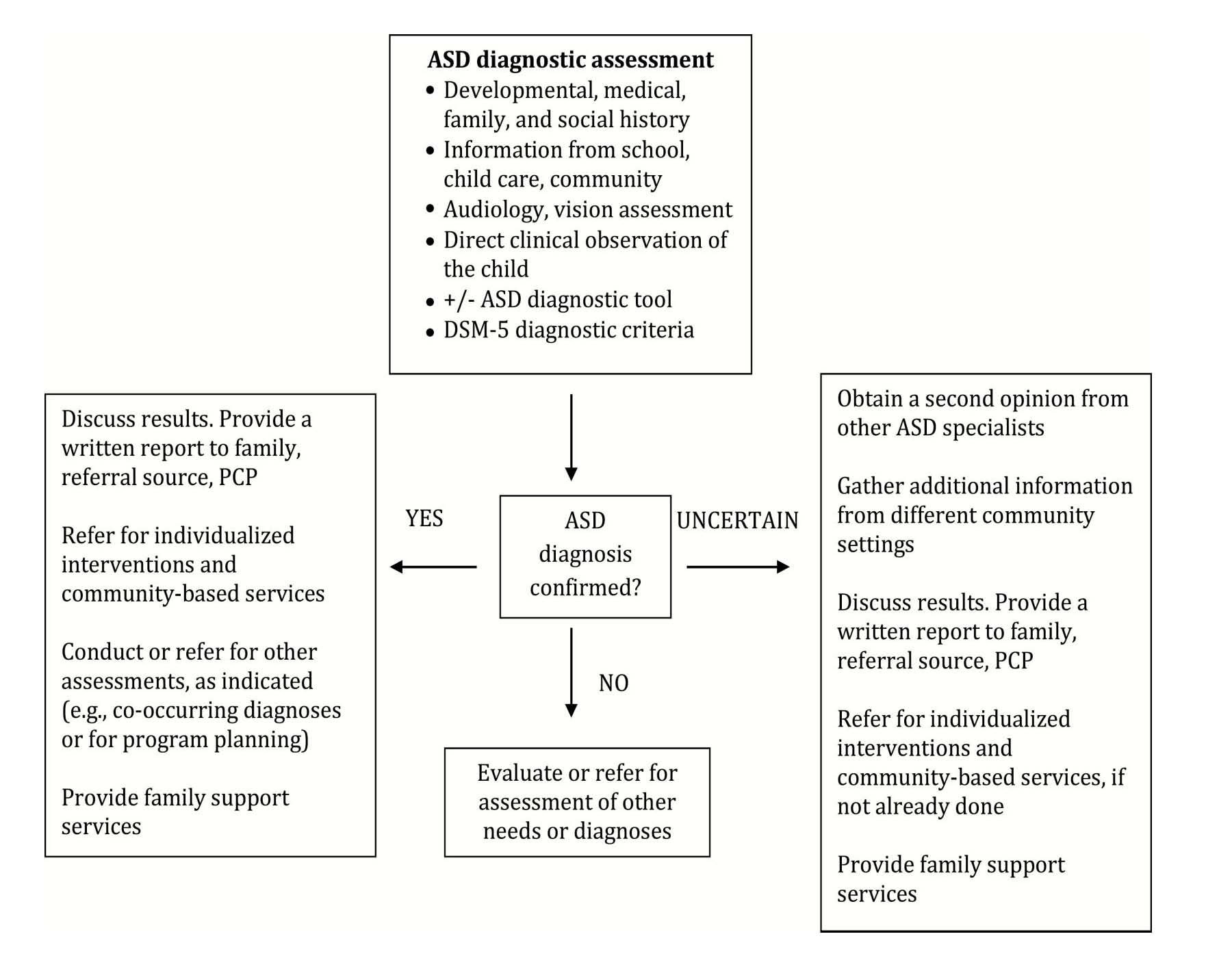

Children with suspected ASD are often first identified by a paediatrician, family physician, parent, or another caregiver, and can present with a wide range and severity of symptoms. A ‘one-size-fits-all’ multidisciplinary team diagnostic approach is inefficient, and contributes to long wait times [1][16]. This statement proposes three ASD diagnostic approaches, the choice of which depends upon the paediatric care provider’s clinical experience and judgment, and the complexity of symptom presentation [8]–[15] and/or psychosocial history (Figure 1). Regardless of the approach taken, open communication, collaboration, and consent to share information among professionals may help to achieve diagnostic accuracy and avoid duplication of effort.

Approach 1

When a child’s symptoms clearly indicate ASD, an experienced or trained sole paediatric care provider can independently diagnose ASD, based on clinical judgement and DSM-5 criteria [17], with or without data obtained using a diagnostic assessment tool (Table 1). However, this approach is not sufficient for accessing specialized services in some Canadian jurisdictions [1].

Approach 2

In the shared care model, a clinician has joint responsibility with another health care provider for patient care, which involves exchanging patient information and clinical knowledge. When a child’s symptom presentation is milder, atypical, or complex, or a child is under 2 years of age, a paediatric care provider may use information from an ASD diagnostic assessment tool, and consult with another health care professional with specialized knowledge (e.g., a psychologist) to inform a diagnosis.

Approach 3

In a team-based approach, diagnostic assessment is performed by health care professionals in an interdisciplinary or a multidisciplinary team. While interdisciplinary teams work collaboratively in an integrated, coordinated fashion, multidisciplinary team members work independently from one another but share information, and may (or may not) reach a diagnostic decision by consensus. In some Canadian jurisdictions, only a team-based diagnostic approach is accepted for accessing specialized services [1].

A community clinician may refer to an ASD diagnostic team when a child’s presentation is subtle, or complicated by co-existing health concerns, or when a child has a complex medical or psychosocial history. Any of these factors can make diagnostic determinations more difficult. Although diagnostic certainty may be improved by drawing on specialists’ expertise [3]–[15], this team approach is not always required and may prolong wait times unnecessarily. Diagnostic delays can be a barrier to early interventions, especially when some communities have limited access to specialized services or teams [1][2][16]. However, multidisciplinary team evaluations can also help to capture information for treatment or intervention planning, and to optimize access to supportive programs.

| Figure 1. Algorithm and components of an autism spectrum disorder diagnostic assessment. |

|

PURPOSE AND ESSENTIAL COMPONENTS OF AN ASD DIAGNOSTIC ASSESSMENT

There are no diagnostic biomarkers for ASD. This condition is diagnosed clinically, based on information gathered from a detailed history, physical examination, and the observation of specific characteristic behaviours. Most guideline documents have not offered a maximal acceptable wait time for diagnosis [8][11]–[15], although three reputable guidelines recommend a 3- to 6-month interval between referral and assessment [6][7][10]. An expedited ASD diagnostic assessment, or a referral for one, facilitates earlier and potentially concurrent access to educational interventions and community-based services. The three key objectives of the ASD diagnostic assessment are to:

1. Provide a definitive (categorical) diagnosis of ASD. In ambiguous cases (e.g., milder presentation, under the age of 2), a provisional diagnosis can be made, but the child must be monitored carefully, and referred for further, in-depth evaluation. In many jurisdictions, specialized ASD interventions are not available to children with a provisional diagnosis.

2. Explore conditions or disorders that mimic ASD symptoms and identify co-morbidities.

3. Determine the child’s overall level of adaptive functioning, including specific strengths and challenges, and personal interests, to help with intervention planning.

A family-centred approach is essential in the ASD diagnostic process because a substantial amount of time and care is required to listen to and talk with parents and other family members. Understanding the child’s family and medical history, along with current behaviours and individual and family treatment goals, is central to family-centred care. This approach also requires flexible appointment scheduling and anticipating potential barriers to health care access (e.g., socio-economic adversity), as well as considering cultural and religious values [8]–[10]. When families and clinicians do not speak the same language, involving interpretation services is essential for culturally competent care.

The essential elements of an ASD diagnostic assessment are described below.

STEP 1: RECORDS REVIEW

Most diagnosing clinicians begin by reviewing a child’s previous records and interviewing parents and caregivers about their concerns. This process is typically followed by taking a detailed developmental history and scheduling an appointment for direct observation and assessment.

Medical records to review

- Birth records and newborn screening results

- Routine well-child visits and any early concerns

- Medical tests completed, prior medical treatments, and medication history

- Specialist evaluations

- Hospitalization history

Other records to review

- Developmental evaluations, including ASD screening

- Other assessments (e.g., hearing, vision, speech-language, psychological, functional behavioural (i.e., the reasons for challenging behaviours), or occupational therapy)

- Other care provider information (e.g., child care staff or teacher observations)

- Educational records (when age-appropriate and available)

STEP 2: INTERVIEWING PARENTS, FAMILY MEMBERS, OR OTHER CAREGIVERS

Information is obtained by asking semi-structured, open-ended questions, and may be integrated with information from a standardized questionnaire completed before or during the interview. Topics include:

- Reasons for referral, and when concerns first emerged

- Pregnancy, birth history, labour, with any delivery or other complications

- Child’s developmental and behavioural history (refer to baby books and home videos, when available)

- Child’s current developmental functioning and behaviours

- Child’s medical history, with focus on ASD-associated difficulties, such as sleep problems, unusual diet, self-injury

- Child’s early intervention and educational history, when available

- Family medical and mental health history, spanning three generations, if possible. Inquire into any history of developmental disability, including ASD, learning difficulty, behavioural problems, as well as genetic conditions. Include psychosocial history, with focus on family violence or trauma, substance abuse, or neglect

- Family functioning, strengths, routines, and resources. Consider possible reactions to an ASD diagnosis, along with individual and family goals

| Table 1. Commonly used ASD diagnostic tools | |||||

|

Diagnostic tool |

Age group |

Time for completion |

Test performance [18] |

Test sample |

Comments |

| Behavioural observation (all available for purchase) | |||||

|

Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule – 2nd edition (ADOS-2)* |

12 months to adult |

45–60 minutes |

Se: 92–100% [3] Sp: 61–65% PPV: 80–84% NPV: 81–100% |

ASD and non-ASD patients; clinical sampling |

Social interaction, play, communication, behaviours and interests |

|

Childhood Autism Rating Scale – 2nd edition (CARS-2)* |

2+ years |

20–30 minutes |

Se: 89–94% [3] Sp: 61–100% PPV: 71–100% NPV: 46–56% |

Clinically referred children |

15-item checklist. Incorporates information from parents |

| Parent/Caregiver interviews (all available for purchase) | |||||

|

Diagnostic tool |

Age group |

Time for completion |

Test performance [18] |

Test sample |

Comments |

|

Autism Diagnostic Interview- Revised (ADI-R)* |

2 years to adult |

1.5–3 hours |

Se: 53–90% [3] Sp: 67–94% PPV: 82–98% NPV: 26–68% |

Clinically referred. High to low risk for ASD |

Social interaction, communication, behaviours and interests. Mostly used for research |

|

Social Responsiveness Scale – 2nd edition (SRS-2); preschool and school-aged versions |

2.5–4.5 years; 4–18 years |

15–20 minutes |

Se: 75–78% Sp: 67–94% PPV: 93% |

442 children with or without ASD |

65 items: social awareness, cognition, communication and motivation, repetitive behaviours, and interests |

|

Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disorders (DISCO)* |

Any age |

Up to 3 hours |

Se: 96% [19] Sp: 79% |

Children with different levels of ID |

Detailed, semi-structured interview, with a dimensional approach. Mostly used for research |

|

Developmental, Dimensional and Diagnostic Interview (3di)* [20] (Computerized) |

3+ years |

Up to 2 hours |

Se: 84–100% [3] Sp: 54–98% |

Children with or without ASD |

740 items: demographics, intensity of ASD symptoms, and potential co-morbidities |

| Data drawn from references [8][9][14][17]-[20]. *Training is required to use all tools except for the SRS-2. ASD Autism spectrum disorder; ID Intellectual disability; NPV Negative predictive value; PPV Positive predictive value; Se Sensitivity; Sp Specificity. |

|||||

STEP 3: ASSESSMENT FOR CORE FEATURES OF ASD

This step involves observing and interacting with the child to assess social interaction and communication abilities. Inquire about or observe for patterns of behaviour or interests, with focus on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ASD [17]. Behavioural observation in multiple settings is preferred (e.g., clinic, home, or child care), but most assessments occur in clinical settings. An ASD-specific diagnostic tool may also be used.

Commonly used ASD-specific diagnostic tools

There are two broad categories of ASD diagnostic tools: those based on coding observations and direct interactions with the child (e.g., ADOS-2, CARS-2) [3][18][21], and those based on parent or caregiver interviews (e.g., ADI-R) or questionnaires (e.g., SRS-2) [3][21][22]. Findings from an ASD diagnostic assessment tool cannot be used alone to diagnose ASD [3]. Rather, results should complement the diagnostic process and inform clinical judgement. Clinically useful ASD diagnostic assessment tools have a sensitivity (i.e., they correctly identify children with ASD) and specificity (i.e., they correctly identify children without ASD) of at least 80%. Common age-specific ASD diagnostic tools are summarized in Table 1 [8][9][14][17]-[20].

The most recent Cochrane review of ASD diagnostic tools for preschoolers found that the ADOS has the highest sensitivity and comparable specificity to the CARS and ADI-R [22]. In some jurisdictions, the ADOS and ADI-R are required to inform ASD diagnosis [2][5].

STEP 4: COMPREHENSIVE PHYSICAL EXAMINATION AND ADDITIONAL INVESTIGATIONS

The physical exam assesses whether there are medical causes or associations with the child’s behavioural presentation. Findings can help to guide treatment and intervention planning and include:

- Height and weight

- Head circumference (20% of individuals with ASD are macrocephalic)

- Skin examination for signs of neurofibromatosis or tuberous sclerosis (e.g., using Wood’s lamp)

- Neurological examination

- Congenital anomalies and dysmorphic features (e.g., large or prominent ears)

- Hearing and vision assessment with referral to audiologist, optometrist, or ophthalmologist, as needed

- Only if clinically indicated, laboratory testing or further investigations may include:

- Electroencephalogram (EEG) (e.g., for seizures)

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (e.g., for microcephaly, seizures, abnormal neurological exam)

- Metabolic testing (e.g., for cyclic vomiting, lethargy with minor illness, developmental regression, and seizures) [23]

- Chromosomal microarray genetic testing should be offered for any children with a developmental disability, dysmorphic features, or congenital anomaly [24][25]

- Blood lead levels, when the child exhibits developmental delay or pica, or lives in a high-risk environment

STEP 5: CONSIDER DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES AND CO-OCCURRING CONDITIONS

When making an ASD diagnosis, it is important to consider other disorders that might overlap or mimic ASD symptoms. Table 2 summarizes common differential diagnoses that may also co-occur with ASD.

STEP 6: ESTABLISHING AN ASD DIAGNOSIS

A trained clinician uses DSM-5 criteria along with clinical judgment to differentiate ASD from other developmental disorders [1]. For a description of DSM-5 criteria, see Table 1, Early Detection for Autism Spectrum Disorder, in the companion statement published in this issue.

STEP 7: COMMUNICATING ASD DIAGNOSTIC ASSESSMENT FINDINGS

Ideally, both parents and the child (when age and otherwise appropriate) should be invited for a face-to-face appointment shortly after the ASD diagnostic evaluation. This visit should be conducted in the family’s primary language, using an interpreter if necessary, with discussion of assessment findings, prognosis, and recommended supportive resources. When an in-person appointment is not possible due to remote location or travel restrictions, a telephone- or video-conference should be arranged instead.

This appointment must be handled in a sensitive, supportive manner. Parents should be given time to process the information being given and to ask questions, without distractions or interruptions. Asking parents what questions they have (rather than if they have questions) is one helpful way to open a conversation. When both parents are involved in the child’s care, they should be present together for the feedback meeting. A lone parent should be encouraged to bring a support person to this appointment.

The information below should be provided verbally and as part of a comprehensive, informative written report, with terms and references suitable for a lay audience.

| Table 2. Common differential diagnoses and co-occurring conditions in ASD [10][14] |

|

Neurodevelopmental disorders Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder |

|

Mental/Behavioural disorders Anxiety disorders |

|

Genetic conditions Fragile X syndrome |

|

Neurological and other medical conditions Cerebral palsy |

| *Social (pragmatic) communication disorder and ASD are mutually exclusive. **There are many other chromosomal abnormalities and genetic syndromes associated with ASD [26] ASD Autism spectrum disorder. |

- A clear statement confirming that the child does (or does not) have ASD (e.g., ‘(Child’s name] meets DSM-5 criteria for a diagnosis of ASD’). Avoid indirect language (e.g., ‘(Child’s name’s) behaviour is consistent with a diagnosis of ASD’) because it can be confusing. In some cases, a provisional diagnosis may be appropriate, especially when targeted local services are available.

- The reasons for the referral, and the child’s relevant developmental and family history.

- Summary of pre-evaluation test results, and a review of all relevant records.

- Summary from the family interview and direct observations of the child that support the ASD diagnosis.

- Description of the diagnostic tools used, and clinicians who conducted the evaluation.

- Description of how the child’s presenting symptoms, behaviours, and history meet DSM-5 criteria.

- Co-occurring or suspected conditions that have been identified, diagnosed, or require further investigation.

- Current functioning levels and recommended supports.

- Referrals for services, with individualized intervention recommendations based on the child’s needs

- Recommended additional assessments, when needed

- Resources for parents (e.g., information about ASD, support and parent advocacy groups, funding opportunities) and siblings, and a follow-up plan.

Sharing documents

Share the written report with the child’s family, the referring physician, other health care providers, and educational professionals who are involved with the child’s care plan, with appropriate consents.

What to do when a categorical ASD diagnosis cannot be determined at the time of assessment.

When a diagnosis is unclear, consider:

- Gathering additional information from other sources.

- Observing the child in a different setting (e.g., home, child care).

- Obtaining a second opinion from a specialized tertiary ASD team.

- Conducting a repeat assessment (e.g., after initiation of therapy or school entry) to clarify potential diagnoses. When children have developmental concerns that do not meet ASD criteria, they should be referred for further assessment and for services that address these concerns.

STEP 8: COMPREHENSIVE ASSESSMENT FOR INTERVENTION PLANNING

After a child has been diagnosed with ASD, the paediatric clinician’s role is to ensure that a comprehensive needs assessment for treatment and intervention planning is considered, when this step was not part of initial diagnostic evaluation. This may involve advocating for further assessment if it appears that a lack of clarity about the child’s functioning may undermine effective planning. This assessment may recur or be revisited at different points throughout child or adolescent development, and in many cases will occur within the context of the child's educational or treatment program. Understanding overall levels of functioning in several domains, including strengths, skills, challenges, and needs, helps with developing effective, individualized treatment and management planning. Such plans should also consider both individual and family concerns, priorities, and resources. The needs assessment may evaluate:

- Cognitive and academic functioning

- Speech, language, and communication skills

- Sensory and motor functioning, and sensory sensitivities

- Adaptive functioning (e.g., self-help skills)

- Behavioural and emotional functioning (e.g., anxiety, self-esteem issues)

- Physical health and nutrition

The extent of comprehensive assessment for intervention planning is influenced by the approach used for initial ASD diagnostic evaluation.

Approach 1

Diagnostic evaluations conducted by a sole paediatric care provider tend to focus on the core domains of ASD. Therefore, referral to an interdisciplinary team or to multiple professionals for a comprehensive needs assessment may be required, particularly when planning will not be conducted in the context of a child’s educational or treatment program.

Approach 2

Diagnostic evaluations carried out with a shared care partner can provide additional information for intervention planning (e.g., insight into cognitive functioning). Further referrals may only be needed to understand additional areas of functioning (e.g., sensory or motor), if indicated.

Approach 3

When a child is evaluated by a multidisciplinary team, diagnostic evaluation and assessment for intervention planning are more likely to occur concurrently. Additional assessments may or may not be necessary.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS IN DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Age

Although a definitive diagnosis for ASD is possible in children under 2 years of age, this can be challenging. Children this young often exhibit symptoms that are subtle or less distinguishable from other developmental delays—or even from typical development [8][10]. Very young children who receive a provisional ASD diagnosis will need a timely follow-up evaluation or referral for further assessment because their symptoms can change substantially during development [27]. The importance of confirming or ruling out an ASD diagnosis as early as possible cannot be overstated.

Sex

ASD is diagnosed four times more frequently in boys than girls [27]. In younger siblings of children with ASD, the boy:girl ratio is approximately 3:1 [28]. When symptoms are equally severe, boys are more likely to be diagnosed. Gendered differences in symptom presentation may contribute to later diagnosis in girls [8]–[10]. Also, the evidence suggests that girls are better able to ‘camouflage’ symptoms and use compensatory strategies to overcome communication and social difficulties [13]. Clinicians should be aware that girls are probably underdiagnosed for ASD [29][30].

Culture and language

Current evidence further suggests that children from racial or ethnic minorities are diagnosed later than their peers in the general population [6][8][22]. It is unclear the extent to which this disparity is attributable to limited access to diagnostic services, interpretation of symptoms by families, health care system-related factors [14], or an interplay thereof. Cultural factors can impact many aspects of health care, including how ASD is understood, interpreted, and accepted in different communities. Cultural factors may, in turn, affect help-seeking behaviours [31].

Rural or remote regions

Children living in rural or remote communities receive an ASD diagnosis later than peers living in urban areas [6][8][32]. Shared care between a local primary care provider and ASD specialist(s) further away can be facilitated through telehealth (especially video-conferencing services) and by itinerant developmental clinics which travel to rural or remote areas on a seasonal schedule [6][8][32]. Capacity building in underserved communities should be a priority.

NEXT STEPS FOLLOWING A CONFIRMED ASD DIAGNOSIS

When an ASD diagnosis has been confirmed, a community-based paediatrician or primary care provider plays a vital role in supporting both child and family. Physicians provide routine health care, manage co-occurring medical conditions, and coordinate care among medical, educational, community, and social care professionals. For additional information on condition management, read the companion statement published in this issue, including links to online resources.

Funding: Production of these guidelines has been made possible through funding from the Public Health Agency of Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the view of the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Potential Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Zwaigenbaum reports personal fees from Roche - Independent Data Monitoring Committee (iDMC), outside the submitted work. There are no other disclosures. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

CANADIAN PAEDIATRIC SOCIETY AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER GUIDELINES TASK FORCE

Members: Mark Awuku MD (CPS Community Paediatrics Section), Jessica Brian PhD (co-Chair), Susan Cosgrove, Pam Green NP, Elizabeth Grier MD (College of Family Physicians of Canada), Sophia Hrycko MD (Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry), Angie Ip MD, James Irvine MD, Anne Kawamura MD (CPS Developmental Paediatrics Section), Sheila Laredo MD PhD (Canadian Autism Spectrum Disorders Alliance), William Mahoney MD (CPS Mental Health Section), Patricia Parkin MD, Melanie Penner MD, Mandy Schwartz MD, Isabel Smith PhD, Lonnie Zwaigenbaum MD (co-Chair)

Principal authors: Jessica A. Brian PhD, Lonnie Zwaigenbaum MD, Angie Ip MD

References

- Penner M, Anagnostou E, Ungar WJ. Practice patterns and determinants of wait time for autism spectrum disorder diagnosis in Canada. Mol Autism 2018;9(1):16.

- Penner M, Anagnostou E, Andoni LY, Ungar WJ. Systematic review of clinical guidance documents for autism spectrum disorder diagnostic assessment in select regions. Autism 2018;22(5):517–27.

- Zwaigenbaum L, Penner M. Autism spectrum disorder: Advances in diagnosis and evaluation. BMJ 2018;361:k1674.

- Anagnostou E, Zwaigenbaum L, Szatmari P, et al. Autism spectrum disorder: Advances in evidence-based practice. CMAJ 2014;186(7):509–19.

- Dua K. Standards and Guidelines for the Assessment and Diagnosis of Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in British Columbia: An Evidence-based Report Prepared for the British Columbia Ministry of Health Planning, March 2003. http://www.phsa.ca/Documents/asd_standards_0318.pdf (Accessed March 19, 2019).

- The Miriam Foundation. Screening, Assessment and Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Young Children: Canadian Best Practice Guidelines. https://www.miriamfoundation.ca/DATA/TEXTEDOC/Handbook-english-webFINAL.pdf (Accessed March 19, 2019).

- New Zealand Ministy of Health. New Zealand Autism Spectrum Disorder Guideline, 2nd edn., 2016. Wellington, NZ. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-zealand-autism-spectrum-disorder-guideline (Accessed March 19, 2019).

- Johnson CP, Myers SM; American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children With Disabilities. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2007;120(5):1183–215.

- Missouri Autism Guidelines Initiative. Autism Spectrum Disorders: Missouri Best Practice Guidelines for Screening, Diagnosis, and Assessment; A 2010 Consensus Publication. https://www.autismguidelines.dmh.mo.gov/ (Accessed March 19, 2019).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Autism Spectrum Disorder in Under 19s: Recognition, Referral and Diagnosis (Clinical guideline 128) London, UK: NICE, 2011 (updated December 2017). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg128 (Accessed March 20, 2019).

- University of Connecticut School of Medicine and Dentistry, Connecticut Guidelines for a Clinical Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder, 2013. Articles – Patient Care, 45. http://digitalcommons.uconn.edu/pcare_articles/45 (Accessed March 20, 2019).

- Volkmar F, Siegel M, Woodbury-Smith M, King B, McCracken J, State M; American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Committee on Quality Issues (CQI). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014;53(2):237–57.

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Assessment, Diagnosis and Interventions for Autism Spectrum Disorders. Edinburgh, Scotland: 2016. http://www.sign.ac.uk (Accessed March 20, 2019).

- Whitehouse AJO, Evans K, Eapen V, Wray J. A National Guideline for the Assessment and Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Australia. Brisbane, Australia: Autism Cooperative Research Centre (CRC), 2018.

- HAS Haute Autorité de Santé. Autism spectrum disorder: Warning signs, Detection, Diagnosis and Assessment in Children and Adolescents. Best practice guidelines, February 2018. www.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_468812/en/autism-spectrum-disorderwarning-signs-detection-diagnosis-and-assessment-in-children-and-adolescents?cid=fc_ 1249601&userLang=en&portal=r_1482172&userLang=en (Accessed August 2, 2019).

- Yuen T, Carter MT, Szatmari P, Ungar WJ. Cost-effectiveness of universal or highrisk screening compared to surveillance monitoring in autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2018;48(9):2968–79.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edn. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

- Falkmer T, Anderson K, Falkmer M, Horlin C. Diagnostic procedures in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic literature review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013;22(6):329–40.

- Maljaars J, Noens I, Scholte E, van Berckelaer-Onnes I. Evaluation of the criterion and convergent validity of the diagnostic interview for social and communication disorders in young and low-functioning children. Autism 2012;16(5):487–97.

- Skuse D, Warrington R, Bishop D, et al. The developmental, dimensional and diagnostic interview (3di): A novel computerized assessment for autism spectrum disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004;43(5):548–58.

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Screening and Diagnostic Tools for Autism Spectrum Disorder in Children: A Review of Guidelines, July 2013, CADTH Rapid Reponse Report. https://www.cadth.ca/screening-and-diagnostic-tools-autism-spectrum-disorder-children-review-guidelines (Accessed March 20, 2019).

- Randall M, Egberts KJ, Samtani A, et al. Diagnostic tests for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in preschool children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;7:CD009044.

- Bélanger SA, Caron J. Canadian Paediatric Society, Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Committee. Evaluation of the child with global developmental delay and intellectual disability. Paediatr Child Health 2018;23(6):403–19.

- Miller DT, Adam MP, Aradhya S, et al. Consensus statement: Chromosomal microarray is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. Am J Hum Genet 2010;86(5):749–64.

- Genetics Education Canada – Knowledge Organization (GECKO). Microarray: Updated June 2019. http://geneticseducation.ca/educational-resources/gec-ko-on-the-run/chromosomal-microarray/ (Accessed September 24, 2019).

- Vorstman JA, Parr JR, Moreno-De-Luca D, Anney RJ, Nurnberger Jr. JI, Hallmayer JF. Autism genetics: opportunities and challenges for clinical translation. Nat Rev Genet 2017;18(6):362.

- Zwaigenbaum L, Bryson S, Lord C, et al. Clinical assessment and management of toddlers with suspected autism spectrum disorder: Insights from studies of high-risk infants. Pediatrics 2009;123(5):1383–91.

- Ozonoff S, Young GS, Carter A, et al. Recurrence risk for autism spectrum disorders: A Baby Siblings Research Consortium Study. Pediatrics 2011;128(3):e488–95.

- Baio J, Wiggins L, Christensen DL, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years – Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ 2018;67(6):1–23.

- Lai MC, Lombardo MV, Auyeung B, Chakrabarti B, Baron-Cohen S. Sex/gender differences and autism: Setting the scene for future research. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;54(1):11–24.

- Khanlou N, Haque N, Mustafa N, Vazquez LM, Mantini A, Weiss J. Access barriers to services by immigrant mothers of children with autism in Canada. Int J Ment Health Addict 2017;15(2):239–59.

- Antezana L, Scarpa A, Valdespino A, Albright J, Richey JA. Rural trends in diagnosis and services for autism spectrum disorder. Front Psychol 2017;8:590.

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.