Position statement

Somatic symptom and related disorders: Guidance on assessment and management for paediatric health care providers

Posted: Nov 20, 2024

Principal author(s)

Natasha Ruth Saunders MD MSc, Anne Kawamura MD, Olivia MacLeod MD, Alexandra Nieuwesteeg MD, Claire De Souza MD; Canadian Paediatric Society, Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Committee

Canadian Paediatric Society 30(4):331–337

Abstract

Somatic symptom and related disorders (SSRDs) pose significant challenges in paediatric health care due to their impacts on child and adolescent well-being, functioning, and family systems. This statement offers comprehensive guidance to health care providers on the assessment and management of SSRDs as well as communication strategies for clinical encounters. Specific SSRD diagnoses are outlined along with common clinical presentations and recommended approaches to medical investigations and patient/family communication early in the diagnostic journey. Evidence-based treatments for SSRDs once a diagnosis has been established are delineated. Psychoeducational approaches that help to shift the onus of care from unnecessary medical testing and procedures, thereby shortening the diagnostic journey, and promote more functional, rehabilitative care therapies, are reviewed. Specific strategies to support patients and their families and validate their perspectives are outlined.

Keywords: Conversion disorder; Functional neurological symptom disorder; Mind-body; Paediatrics; Somatization

Abbreviations

EDS, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome; FNSD, functional neurologic symptom disorder; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; PNES, psychogenic non-epileptiform seizures; POTS, postural orthostatic tachycardia; SSRD, somatic symptom and related disorder

Background

Somatic symptom and related disorders (SSRD) refer to a category of mental disorders that commonly affect children and adolescents. Individuals with SSRDs have high health system utilization. Patients present across the care continuum in primary care, consultant paediatric care, emergency departments, and hospital inpatient units[1]-[3]. This position statement supports clinicians caring for children and adolescents across the care spectrum in three ways: 1) By helping them to identify, engage, and prepare patients (and families) for mental health assessment and treatment (while shifting away from medically unnecessary diagnostic testing and procedures); 2) By promoting a functional, rehabilitative approach, including early return to school and activities; and 3) By offering strategies to monitor and manage physical and mental health symptom evolution.

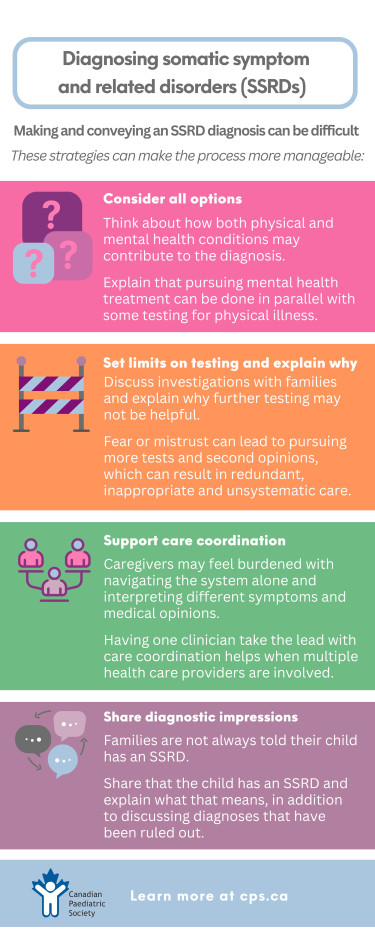

For clinicians, making and conveying a diagnosis of an SSRD can be difficult. The focus here is to address issues early in the diagnostic odyssey, when young patients have not yet or are just beginning to understand how emotions and stress are contributing to their physical symptoms. Long-term psychotherapeutic management strategies are beyond scope of this document but should be part of treatment planning.

Defining somatization and SSRDs

Somatization describes the experience whereby emotions, either positive (e.g., excitement) or negative (e.g., worry), and thoughts are expressed as physical signs or symptoms. Somatization is a normal and involuntary physical response to an emotional stimulus or stressor that all people experience[4]. For example, signs of somatization may include axillary sweating when nervous, pupillary dilatation when fearful, or syncope when surprised. Symptoms of somatization can include abdominal pain when feeling anxious, or fatigue when feeling overwhelmed. Somatization is considered part of a disorder when these bodily signs or symptoms cause significant distress or impairment in daily life. Such signs and symptoms of an SSRD may occur as an isolated disorder but may also co-occur alongside another medical condition[4].

According to the DSM-5 -TR[4], SSRDs comprise a cluster of five specific disorders that include: 1) somatic symptom disorder, 2) functional neurological symptom disorder (FNSD or conversion disorder), 3) illness anxiety disorder, 4) psychological factors affecting other medical conditions, and 5) factitious disorder. See Table 1 for inclusion criteria and a brief description of specific disorders. The focus of this statement is on somatic symptom disorder and FNSD because they are the two SSRD types that present most commonly to general paediatric clinicians.

|

Table 1. Types of somatic symptom and related disorders |

|||

|

Disorder name |

Other common or historic terms |

Key features |

Behaviours, symptoms, or diagnoses young patients may present with |

|

Somatic symptom disorder (DSM-5-TR) |

“Functional” “Medically unexplained symptoms” (term has fallen out of favour) “Non-organic” Bodily distress disorder (ICD-11) Somatoform disorders (ICD-10) |

One or more somatic symptoms that are distressing or significantly disrupt daily life. Excessive thoughts, feelings, or behaviours related to somatic symptoms, manifested as one or more of the following:

|

Chronic headaches Dizziness Brain fog Chronic nausea Chronic pain Fatigue |

|

Functional neurological symptom disorder (DSM-5-TR) |

Conversion disorder Functional neurological disorder Dissociative neurological symptom disorder (ICD-11) Dissociative disorders (ICD-10) |

One or more symptoms of altered voluntary motor or sensory function without evidence of a neurological diagnosis (e.g., normal EEG during a seizure-like episode) [5][6]. The symptom(s) cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. |

Psychogenic non-epileptiform seizures (previously called pseudoseizures) Paralysis or weakness |

|

Illness anxiety disorder |

Hypochondriasis |

Preoccupation with having or acquiring a serious illness. High anxiety about health status, resulting in excessive health-related behaviours or maladaptive avoidance. |

Excessive care-seeking behaviours surrounding actual or imagined illness |

|

Psychological factors affecting other medical conditions |

Clinically significant psychological or behavioural factors that adversely affect an individual’s medical condition and increase their risk for suffering, death, or disability. |

Poor or non-adherence to prescribed medications or treatments Ignoring symptoms Anxiety or stress exacerbating asthma or migraine symptoms |

|

|

Factitious disorder Factitious disorder imposed on another person |

Munchausen’s disorder Munchausen by proxy

|

Purposeful falsification of symptoms or induction of injury, with intent to deceive. By contrast with the previous four disorders, factitious disorder is thought to be under the patient’s control. |

|

DSM-5-TR Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, text revision; ICD International Classification of Diseases

SSRD epidemiology

Exact prevalence estimates of SSRDs are uncertain due to the non-specific nature of symptoms and the universal experience of somatization that does not cross the ‘disorder’ threshold. Published estimates from European studies range from 4.1% to 12.6% of children and adolescents who at some point meet criteria for diagnosis[7]-[9]. In Ontario, over 33,000 children, youth, and young adults (up to 24 years old) were identified in health records to have SSRDs over a 7-year period[10]. Population-level data from other Canadian provinces were not yet published at time of writing. Individuals with SSRDs have high health system utilization rates (and related costs), school absenteeism, high rates of disability, and variable prognoses[10]-[13]. For children and youth hospitalized with an SSRD, mean health system costs were a combined $52,621 CAD in the year before and after diagnosis, on a par with some of the most medically complex children[14]. Importantly, after receiving an SSRD diagnosis, only 40% of patients will see a physician within the next year for a mental health concern[10].

Common clinical presentations

Children and adolescents with SSRDs present with non-specific signs and symptoms across the spectrum of general paediatrics (e.g., brain fog, fatigue, dizziness, joint pain, abdominal pain, hypermobility) and subspecialty paediatric areas (e.g., seizures and sensory changes (neurology), nausea and dysphagia (gastroenterology), orthostatic intolerance (cardiology), joint pain (rheumatology), and anorexia or pelvic pain (adolescent medicine)). Patients may also present with questions about or self-diagnoses of disorders that have similar common symptoms and multi-systemic presentations[15]-[17], including: 1) postural orthostatic tachycardia, 2) post-COVID-19 condition, 3) chronic Lyme disease, and 4) Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Because these conditions are commonly asked about, clinicians will benefit from an understanding of diagnostic criteria and management pathways for these four conditions[18]-[21]. Such knowledge enables a more individualized assessment of, and approach to, patient concerns regarding these diseases, and can help guide further testing and referral, when appropriate.

Considerations for investigation

Clinicians often serve as ‘gatekeepers’ for diagnostic testing and evaluation. In the context of multiple and non-specific symptoms, clinicians and patients may worry about missing important or obvious physical health conditions. Clinicians must consider how to use testing judiciously and the urgency with which to investigate symptoms. A decision to investigate further requires significant clinical judgement and can be guided by pattern recognition. The extent of testing should also be based on potential benefits (i.e., likelihood of finding a physical health diagnosis, family reassurance) versus the risks of invasive procedures (e.g., sedation for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or endoscopy), cost to families or the health care system, or a discovery of incidental findings. Regardless of the extent of testing, it is important when pursuing diagnostic investigations to frame the clinical impression and process for patients and families using a holistic bio-psycho-social[22][23] approach rather than a biomedical lens alone. A holistic approach considers the dual role of physical and mental health conditions that may be contributing to ultimate diagnoses[22][24]. Table 2 [21][25]-[33] outlines common tests to be considered when faced with non-specific symptoms that suggest an SSRD and when these symptoms overlap with other important diagnostic indications.

|

Table 2. Common testing considerations for SSRDs |

|

|

Symptom |

Testing |

|

Orthostatic intolerance |

Orthostatic vital signs, consider 10-minute stand test when feasible[25], Beighton’s score[26][27], CBC[21], cortisol[21], electrolytes |

|

Seizure-like episodes |

EEG |

|

Flushing/urticaria |

Diagnostic/therapeutic trial of antihistamine, consider serum tryptase for mast cell activation syndrome[28][29] |

|

Chronic fatigue/brain fog |

CBC, cortisol, electrolytes, ALT, EBV serology, Cr, TSH, CRP/ESR, ferritin, B12, HbA1C |

|

Dysphagia |

If progressive, consider upper GI contrast study +/− upper endoscopy |

|

Headaches |

None, unless red flags or abnormal neurological examination[30-32] |

|

Recurrent abdominal pain |

ALT, albumin, CBC, CRP/ESR, celiac screen, ferritin, urinalysis, abdominal ultrasound[33] |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CBC, complete blood count; CRP/ESR, C-reactive protein/erythrocyte sedimentation rate; Cr, creatine; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; EEG, electroencephalography; GI, gastrointestinal; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone

Strategies for clinical encounters

Much has been written about how to approach families regarding mental health following diagnosis of an SSRD, including sample scripts[34][35]. There is far less clinical guidance on approach at earlier phases of disease, before the concept of mind-body connection has been introduced or fully understood, or when diagnostic testing is at an early stage[36].

The approach to a child or adolescent with an SSRD—and their families—depends on the following variables: 1) Where they are in the diagnostic journey; 2) How well their physical health symptoms have been addressed; 3) How ‘in-tune’ they are to the mind-body connection and their openness to discussing the role of stressors; and 4) How ready they are to engage in discussions about mental health. Basic guidance for early encounters follows here:

- Walk a parallel journey. While gathering health information and providing a diagnostic formulation to the family, consider and share the contribution of physical and mental health conditions toward the differential diagnosis[37]. Many SSRD presentations have a physical trigger with a biological basis that explains symptom experience. For example, an adolescent with a febrile viral illness causing fatigue and abdominal pain may experience persistent symptoms and impairment due to predisposing, precipitating, or perpetuating factors. Similarly, a child with inflammatory bowel disease may develop functional abdominal pain that flares with worry about inflammation from their Crohn’s disease. Serotonergic mechanisms regulating stress responses in the brain are also present in the gut, which helps explain the interaction between stress and gastrointestinal symptoms[38]. Explain that the pursuit and treatment of a mental health diagnosis will not necessarily preclude further testing for additional physical causes, especially as symptoms evolve. Rather, testing can be conducted in parallel.

- Set limits on investigations and share your rationale. Because patients and families often feel dismissed, misunderstood, and concerned about their own (or a child’s) well-being, they may worry excessively that something is being missed[39]. Mistrust or fear may, in turn, lead to steadfast pursuit of investigations and second opinions. Care then becomes poorly coordinated, redundant, and unsystematic, with families receiving inconsistent messaging. This cycle perpetuates feelings of being unheard, invalidated, and distressed. For the child, the cycle can lead to inappropriate testing, heightened anxiety, possible complications, and further delays in mental health treatment.

For example, explain to the family of a child with abdominal pain and hard, infrequent stools that constipation is a clinical diagnosis and not based on an x-ray. They may also need to hear that the likelihood of finding pathology on colonoscopy is low when the child’s exam, labs, and imaging do not support a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Be sure to discuss the potential harms of invasive testing (e.g., sedation, bleeding), and share which signs or symptoms (e.g., unexplained weight loss or anemia) to watch for that might indicate further investigations are needed. Take time to explain the clinical basis for and against specific investigations requested by the family (“Why can’t we just do an MRI?”, “Can’t you just run some labs?”). While outlining an approach to testing takes time, it helps avert invasive and unnecessary procedures and tests in a child and, importantly, the family will feel more ‘heard’ when engaged in shared decision-making.

- Quarterback care and communication. The families of children or adolescents with SSRDs use the health system frequently[10], often seek multiple opinions, and may consequently be negatively flagged and ‘labelled’. These health-seeking behaviours can be both the result of and contribute to feeling chronically invalidated, abandoned, and delegitimized[39]. Caregivers are often burdened with navigating the health care system and interpreting the opinions they receive. Isolation can add to confusion and mistrust. However, having one clinician take the lead for care coordination can be immensely helpful when multiple health care providers are involved. Sharing clinic notes with a child’s ‘circle of care’ and holding multi-disciplinary meetings that include primary care can help unify messaging and care coordination. While the practicalities of bringing many clinicians together at the same time can be a challenge, written communication concerning overall impression and the care plan, including how it was conveyed to the family, can be helpful[35]. Further, a written synthesis of findings and opinions for the family, to support and clarify interpretation, may be beneficial.

- Share diagnostic impressions with families. As part of their diagnostic odyssey, the families of children or adolescents with SSRDs are often told what their child does not have (e.g., “This is not cancer, celiac disease, or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome”). Most patients hear much less about what clinicians think they do have. Because it can be difficult to talk about an SSRD diagnosis, clinicians sometimes avoid using the terms “somatization” or “mental health disorder”. But by not giving such a diagnosis when present or suspected, the family’s confusion over what is going on is perpetuated[40]. Further, when a diagnosis of an SSRD has not been given, this prevents them from receiving evidence-based psychoeducation, rehabilitation, and psychotherapy.

Treatment approaches

Provide psychoeducation

Explain the mind-body connection and normalize somatization. Offer descriptions of the physiology of stress, the role of neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin receptors in both the brain and the gut), and for FNSD, describe the different brain regions involved (i.e., amygdala, prefrontal cortex, motor cortex). Emphasize that symptoms may be understood as a problem with ‘software’ rather than ‘hardware’[41]. Sample scripts that clinicians can use for psychoeducation are available[34][39]. While counselling takes time, it is a critical step toward reducing diagnostic confusion, understanding symptoms, and facilitating diagnosis and timely treatment[39].

Treat co-occurring psychiatric conditions

Many children or adolescents with an SSRD have co-occurring psychiatric disorders with or without overlapping symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, or an eating disorder[42]. Such conditions should be treated concurrently, as per usual guidelines[43], with the most impairing psychiatric disorder prioritized.

Engage in rehabilitation

Some families report that their child will return to activities only when symptoms resolve. However, helping families to shift toward a rehabilitation model, where they take part in activities even when symptoms are present, is preferable. Rehabilitation may include occupational therapy (OT), physiotherapy, or speech-language pathology. The role of rehabilitation for treating SSRDs lacks high quality, evidence-based studies[44][45], but the chronic pain literature [46][47] makes it clear that a multi-modal approach, including rehabilitation services, supports recovery. OT can help with engagement at school and academic accommodations. A physiotherapist can improve mobility by avoiding the initiation of, or reducing ongoing need for, aids such as a walker or wheelchair, which can be difficult to discontinue once they are in place. Physiotherapy can also assist with guiding tolerable activities and prevent deconditioning.

When clinicians encounter a family that is not yet ready to consider the mind-body connection as part of their child’s condition despite significant functional limitations, both parties can feel ‘stuck’. Physiotherapy and OT provide windows of opportunity to introduce a functional, rehabilitative pathway forward. Reassure families that focusing on rehabilitation does not preclude further testing or diagnosis, but rather is intended to support their child and prevent decline.

Support school and activity accommodations

Maintenance of or early return to function should be supported in parallel with ongoing investigation, psychoeducation, medication, or other therapy. School avoidance is common with SSRDs, and accommodations to encourage attendance can be beneficial[7][13]. Engaging with the school for a meeting or by letter (or both), or with an OT for specific accommodations, can facilitate earlier return to normal school activities. Personal education plans are defined by patient need and school resources, but common accommodations include making a quiet room available, allowing noise-cancelling headphones to reduce stimulation, modifying course load with paced return to academic and social expectations, and inviting seated presentations for students with orthostatic intolerance. For patients whose symptoms may be visibly distressing to others (e.g., psychogenic non-epileptiform seizures), provide a letter describing a typical event, how to support the student during an episode, and when school providers might consider calling emergency medical services.

Refer for psychotherapy

The most widely available psychotherapeutic modality for children and adolescents with SSRDs is cognitive behaviour therapy[48][49]. There is also emerging evidence for acceptance and commitment therapy, psychodynamic therapy, and emotion-focused family therapy for treating SSRDs[48][50]. Caregiver coaching includes teaching validation techniques, supporting coping strategies and symptom management, and focusing on individual strengths and abilities despite symptoms.

Recommendations for clinicians

Common barriers to patient or family acceptance of an SSRD diagnosis and treatment include devaluing the symptoms experienced, diagnostic uncertainty, and inadequate explanations for symptom presentation. Strategies to support this diagnosis, symptom management, and the patient and family involved include the following.

- Validate a child or adolescent’s symptoms (“this pain is real”) and their impact on life and family, such as academic and friendship loss, chronic pain, sleepless nights, difficulties working, and mental load.

- Acknowledge the family’s efforts to advocate for their child and the barriers they have faced, such as system navigation, mixed messaging, and counter the notion that “It’s all in your head”.

- Set expectations. Clarify that there may not be a diagnosis immediately, but symptom management and evolution can be supported in the meantime. Inform families of plans to hear from both caregivers and the patient, together and separately.

- Offer families opportunities to share their story and goals. What do they think is going on? What investigations are they hoping for and why? Engagement provides opportunities for them to feel heard and for clinicians to address misconceptions. Offer to consider testing based on pattern recognition and best evidence, after assessing potential benefits and risks.

- Explain the mind-body connection. Use examples that illustrate how emotions, both wanted and unwanted, can present as physical signs, such as armpit sweating when excited, dilated pupils when fearful, goosebumps when scared, “butterflies” when nervous, or fatigue when overwhelmed.

- Rather than focusing on which diagnoses a child or adolescent does not have, share the diagnostic impression of somatic symptom disorder or functional neurological symptom disorder with the patient and family. Use the word “somatization” and normalize the diagnosis by talking openly about patient history and experiences.

- Clarify that engaging in psychological and rehabilitative therapies can happen alongside physical health investigations and treatment. For a reluctant family, the timely management of one distressing symptoms can strengthen the therapeutic relationship over the longer term.

- Support the family with close follow-up, which acknowledges uncertainty, shares their journey, and demonstrates commitment.

- Communicate with other practitioners in the family’s ‘circle of care’ to ensure unified messaging. A phone call or note can go a long way.

- Advocate for health system changes to improve care delivery and remuneration models that reflect the complexity and time required to address the needs of children and adolescents with SSRDs.

Acknowledgements

This position statement was reviewed by the Acute Care, Adolescent Health, and Community Paediatrics Committees of the Canadian Paediatric Society. It has also been reviewed and endorsed by the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

CANADIAN PAEDIATRIC SOCIETY MENTAL HEALTH AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES COMMITTEE (2023-2024)

Members: Anne Kawamura MD (Chair), Johanne Harvey MD (Board Representative), Natasha Saunders MD, Megan Thomas MBCHB, Scott McLeod MD, Ripudaman Minhas MD, Alexandra Nieuwesteeg MD (Resident Member)

Liaisons: Olivia MacLeod MD (Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry), Angela Orsino MD (CPS Developmental Paediatrics Section), Leigh Wincott MD (CPS Mental Health Section)

Author(s): Natasha Ruth Saunders MD MSc, Anne Kawamura MD, Olivia MacLeod MD, Alexandra Nieuwesteeg MD, Claire De Souza MD

Funding

This position statement received no direct funding but was supported by the Canadian Paediatric Society.

Potential Conflict of Interest

Dr. Saunders reported receiving personal fees from the BMJ Group, Archives of Disease in Childhood and an honorarium from the Canadian Guidelines for Post Covid-19 Condition Guideline Team outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

References

- Ibeziako P, Randall E, Vassilopoulos A, et al. Prevalence, patterns, and correlates of pain in medically hospitalized pediatric patients with somatic symptom and related disorders. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry 2021;62(1):46-55. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2020.05.008

- Malas N, Donohue L, Cook RJ, Leber SM, Kullgren KA. Pediatric somatic symptom and related disorders: Primary care provider perspectives. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2018;57(4):377-88. doi: 10.1177/0009922817727467

- Barsky AJ, Orav EJ, Bates DW. Distinctive patterns of medical care utilization in patients who somatize. Med Care 2006;44(9):803-11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000228028.07069.59

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5. 5th edn. Arlington, Va: APA; 2013.

- Aybek S, Perez DL. Diagnosis and management of functional neurological disorder. BMJ 2022;376:o64. doi: 10.1136/bmj.o64

- Krasnik CE, Meaney B, Grant C. A clinical approach to paediatric conversion disorder: VEER in the right direction. Canadian Paediatric Surveillance Program;2013. https://cpsp.cps.ca/uploads/publications/RA-conversion-disorder.pdf

- Janssens KA, Klis S, Kingma EM, Oldehinkel AJ, Rosmalen JG. Predictors for persistence of functional somatic symptoms in adolescents. J Pediatr 2014;164(4):900-05.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.12.003

- Lieb R, Pfister H, Mastaler M, Wittchen HU. Somatoform syndromes and disorders in a representative population sample of adolescents and young adults: Prevalence, comorbidity and impairments. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000;101(3):194-208.

- Lehmann M, Pohontsch NJ, Zimmermann T, Scherer M, Löwe B. Estimated frequency of somatic symptom disorder in general practice: Cross-sectional survey with general practitioners. BMC Psychiatry 2022;22(1):632. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04100-0

- Saunders NR, Gandhi S, Chen S, et al. Health care use and costs of children, adolescents, and young adults with somatic symptom and related disorders. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(7):e2011295. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.11295

- Lacy B, Ayyagari R, Guerin A, Lopez A, Shi S, Luo M. Factors associated with more frequent diagnostic tests and procedures in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2019;12:1756284818818326. doi: 10.1177/1756284818818326

- Goodoory VC, Ng CE, Black CJ, Ford AC. Impact of Rome IV irritable bowel syndrome on work and activities of daily living. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2022;56(5):844-56. doi: 10.1111/apt.17132

- Vassilopoulos A, Poulopoulos NL, Ibeziako P. School absenteeism as a potential proxy of functionality in pediatric patients with somatic symptom and related disorders. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2021;26(2):342-54. doi: 10.1177/1359104520978462

- Cohen E, Berry JG, Camacho X, Anderson G, Wodchis W, Guttmann A. Patterns and costs of health care use of children with medical complexity. Pediatrics 2012;130(6):e1463-70. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0175

- Fikree A, Aktar R, Grahame R, et al. Functional gastrointestinal disorders are associated with the joint hypermobility syndrome in secondary care: A case-control study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015;27(4):569-79. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12535

- de Koning LE, Warnink-Kavelaars J, van Rossum MA, et al. Somatic symptoms, pain, catastrophizing and the association with disability among children with heritable connective tissue disorders. Am J Med Genet A. 2023;191(7):1792-1803. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.63204

- Fisher CJ, Katzan I, Heinberg LJ, Schuster AT, Thompson NR, Wilson R. Psychological correlates of patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Auton Neurosci 2020;227:102690. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2020.102690

- Figoni J, Chirouze C, Hansmann Y, et al. Lyme borreliosis and other tick-borne diseases. Guidelines from the French Scientific Societies (I): Prevention, epidemiology, diagnosis. Med Mal Infect 2019;49(5):318-34. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2019.04.381

- Lantos PM. Chronic Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2015;29(2):325-40. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.02.006

- Tofts LJ, Simmonds J, Schwartz SB, et al. Pediatric joint hypermobility: A diagnostic framework and narrative review. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2023;18(1):104. doi: 10.1186/s13023-023-02717-2

- Raj SR, Fedorowski A, Sheldon RS. Diagnosis and management of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. CMAJ 2022;194(10):E378-e385. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.211373

- Helgeland H, Gjone IH, Diseth TH. The biopsychosocial board—A conversation tool for broad diagnostic assessment and identification of effective treatment of children with functional somatic disorders. Human Systems 2022;2(3):144-57. doi: 10.1177/26344041221099644

- Voigt K, Nagel A, Meyer B, Langs G, Braukhaus C, Löwe B. Towards positive diagnostic criteria: A systematic review of somatoform disorder diagnoses and suggestions for future classification. J Psychosom Res 2010;68(5):403-14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.01.015

- Kozlowska K, Sawchuk T, Waugh JL, et al. Changing the culture of care for children and adolescents with functional neurological disorder. Epilepsy Behav Rep 2021;16:100486. doi: 10.1016/j.ebr.2021.100486

- Plash WB, Diedrich A, Biaggioni I, et al. Diagnosing postural tachycardia syndrome: Comparison of tilt testing compared with standing haemodynamics. Clin Sci (London) 2013;124(2):109-14. doi: 10.1042/CS20120276

- Loganathan P, Herlihy D, Gajendran M, et al. The spectrum of gastrointestinal functional bowel disorders in joint hypermobility syndrome and in an academic referral center. J Investig Med 2024;72(1):162-8. doi: 10.1177/10815589231210486

- Boris JR, Bernadzikowski T. Prevalence of joint hypermobility syndromes in pediatric postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Auton Neurosci2021;231:102770. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2020.102770

- Molderings GJ, Brettner S, Homann J, Afrin LB. Mast cell activation disease: A concise practical guide for diagnostic workup and therapeutic options. J Hematol Oncol 2011;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-4-10

- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS). https://www.aaaai.org/conditions-treatments/related-conditions/mcas (Accessed August 8, 2024).

- Becker WJ, Findlay T, Moga C, Scott NA, Harstall C, Taenzer P. Guideline for primary care management of headache in adults. Can Fam Physician 2015;61(8):670-9.

- Kacperski J, Kabbouche MA, O’Brien HL, Weberding JL. The optimal management of headaches in children and adolescents. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2016;9(1):53-68. doi: 10.1177/1756285615616586

- Klein J, Koch T. Headache in children. Pediatr Rev 2020;41(4):159-71. doi: 10.1542/pir.2017-0012

- Thapar N, Benninga MA, Crowell MD, et al. Paediatric functional abdominal pain disorders. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020;6(1):89. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00222-5

- Ibeziako P, Brahmbhatt K, Chapman A, et al. Developing a clinical pathway for somatic symptom and related disorders in pediatric hospital settings. Hosp Pediatr 2019;9(3):147-55. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2018-0205

- Malas N, Ortiz-Aguayo R, Giles L, Ibeziako P. Pediatric somatic symptom disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2017;19(2):11. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0760-3

- Mariman A, Vermeir P, Csabai M, et al. Education on medically unexplained symptoms: A systematic review with a focus on cultural diversity and migrants. Eur J Med Res 2023;28(1):145. doi: 10.1186/s40001-023-01105-7

- Newlove T, Standford E, Chapman A, Dhariwal A. Pediatric Somatization: Professional Handbook. Vancouver, B.C: BC Children’s Hospital;2021.

- Terry N, Margolis KG. Serotonergic mechanisms regulating the GI tract: Experimental evidence and therapeutic relevance. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2017;239:319-42. doi: 10.1007/164_2016_103

- Boerner KE, Dhariwal AK, Chapman A, Oberlander TF. When feelings hurt: Learning how to talk with families about the role of emotions in physical symptoms. Paediatr Child Health 2022;28(1):3-7. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxac052

- Moulin V, Akre C, Rodondi PY, Ambresin AE, Suris JC. A qualitative study of adolescents with medically unexplained symptoms and their parents. Part 2: How is healthcare perceived? J Adolesc 2015;45:317-26. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.10.003

- Perez DL, Nicholson TR, Asadi-Pooya AA, et al. Neuroimaging in functional neurological disorder: State of the field and research agenda. NeuroImage Clin 2021;30:102623. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2021.102623

- Boerner KE, Coelho JS, Syal F, Bajaj D, Finner N, Dhariwal AK. Pediatric avoidant-restrictive food intake disorder and gastrointestinal-related somatic symptom disorders: Overlap in clinical presentation. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2022;27(2):385-98. doi: 10.1177/13591045211048170

- Bobbitt S, Kawamura A, Saunders N, Monga S, Penner M, Andrews D; Canadian Paediatric Society, Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Committee. Anxiety in children and youth: Part 2 − The management of anxiety disorders. Paediatr Child Health 2023;28(1):52-66. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxac104. https://cps.ca/en/documents/position/anxiety-in-children-and-youth-management

- Sartori R, Tessitore A, Della Torca A, Barbi E. Efficacy of physiotherapy treatments in children and adolescents with somatic symptom disorder and other related disorders: Systematic review of the literature. Ital J Pediatr 2022;48(1):127. doi: 10.1186/s13052-022-01317-3

- Mesaroli G, Munns C, DeSouza C. Evidence-based practice: Physiotherapy for children and adolescents with motor symptoms of conversion disorder. Physiother Can 2019;71(4):400-02. doi: 10.3138/ptc-2018-68

- Whalen KC, Crone W. Multidisciplinary approach to treating chronic pain in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: Critically appraised topic. J Pain Res 2022;15:2893-2904. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S377790

- Seitz T, Stastka K, Schiffinger M, Rui Turk B, Löffler-Stastka H. Interprofessional care improves health-related well-being and reduces medical costs for chronic pain patients. Bull Menninger Clin 2019;83(2):105-27. doi: 10.1521/bumc_2019_83_01

- Abbass A, Lumley MA, Town J, et al. Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for functional somatic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of within-treatment effects. J Psychosom Res 2021;145:110473. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110473

- Abbass A, Town J, Holmes H, et al. Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for functional somatic disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychother Psychosom 2020;89(6):363-70. doi: 10.1159/000507738

- Abbass A, Campbell S, Magee K, Tarzwell R. Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy to reduce rates of emergency department return visits for patients with medically unexplained symptoms: Preliminary evidence from a pre-post intervention study. CJEM 2009;11(6):529-34. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500011799

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.