Position statement

Bronchiolitis: Recommendations for diagnosis, monitoring and management of children one to 24 months of age

Posted: Nov 3, 2014 | Updated: Nov 30, 2021

Principal author(s)

Jeremy N Friedman, Michael J Rieder, Jennifer M Walton; Canadian Paediatric Society, Acute Care Committee, Drug Therapy Committee

Updated by Carolyn Beck, Kyle McKenzie and Laurel Chauvin-Kimoff

Abstract

Bronchiolitis is the most common reason for admission to hospital in the first year of life. There is tremendous variation in the clinical management of this condition across Canada and around the world, including significant use of unnecessary tests and ineffective therapies. This statement pertains to generally healthy children ≤24 months of age with bronchiolitis. The diagnosis of bronchiolitis is based primarily on the history of illness and physical examination findings. Laboratory investigations are generally unhelpful. Bronchiolitis is a self-limiting disease, usually managed with supportive care at home. Groups at high risk for severe disease are described and guidelines for admission to hospital are presented. Evidence for the efficacy of various therapies is discussed and recommendations are made for management. Monitoring requirements and discharge readiness from hospital are also discussed.

Key Words: Respiratory distress; RSV; URTI; Wheezing

Bronchiolitis is a viral lower respiratory tract infection characterized by obstruction of small airways caused by acute inflammation, edema and necrosis of the epithelial cells lining the small airways as well as increased mucus production.[1] Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is responsible for most cases.[2][3] However, other viruses, including human metapneumovirus (HMPV), influenza, rhinovirus, adenovirus and parainfluenza can all cause a similar clinical picture.[4] Coinfection with multiple viruses occurs in 10% to 30% of young hospitalized children.[5] Primary infection does not confer protective immunity and reinfections continue to occur into adulthood, with repeat infections being generally milder. In Canada, RSV season usually begins between November and January, and persists for four to five months.[6]

Bronchiolitis affects more than one-third of children in the first two years of life and is the most common cause for admission to hospital in their first year. Over the past 30 years, hospitalization rates have increased from 1% to 3% of all infants.[1][7][8] Rising admissions have been costly for the health care system,[9] and reflect significant morbidity[10] and impact on families.

Despite the existence of numerous clinical practice guidelines, including the updated American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) clinical practice guideline published in 2014,[11] there is tremendous variation[12] in approaches to diagnosis, monitoring and management. Initiatives to standardize care for bronchiolitis have demonstrated decreased use of diagnostic testing and resource utilization, along with cost reduction and improved outcomes.[7][13] However, while there has been some decrease in testing and treatments since the release of the AAP recommendations,[14] uptake has not been widespread.

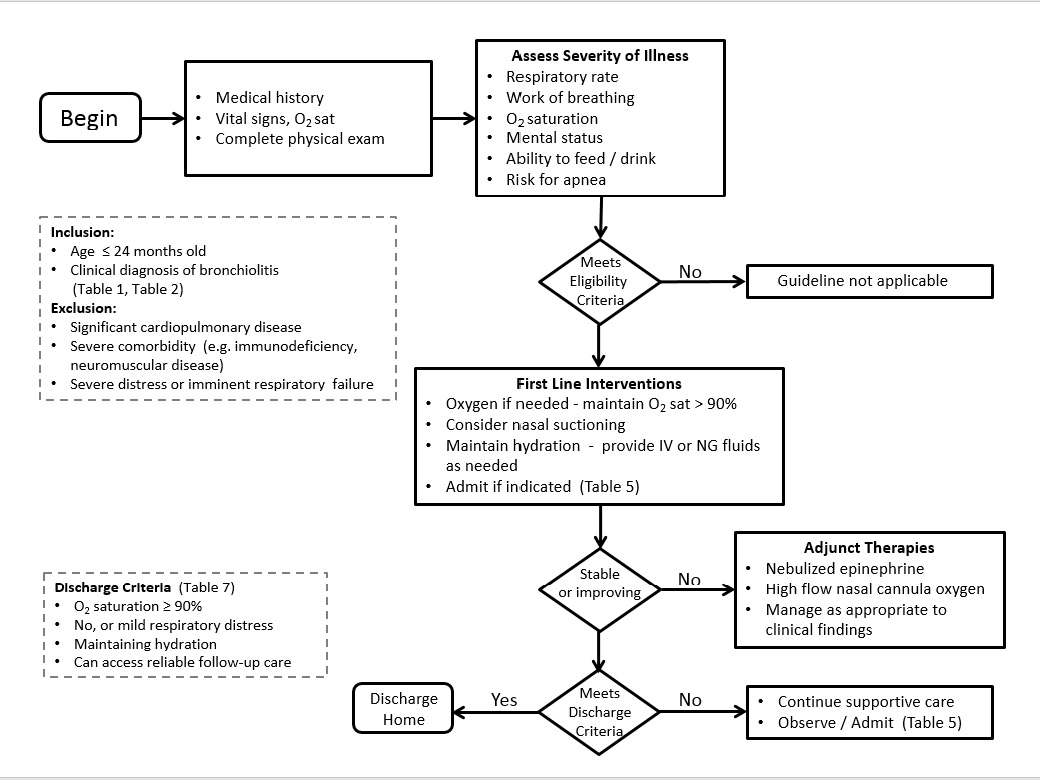

The goals of this statement are to build on the comprehensive peer-reviewed AAP statement[1] by incorporating new evidence, while providing the clinician with recommendations to help guide diagnosis, monitoring and management of previously healthy children one to 24 months of age who present with signs of bronchiolitis (Figure 1). These recommendations are intended to support a decrease in the use of unnecessary diagnostic studies and ineffective medications and interventions. This statement does not apply to children with chronic lung disease, immunodeficiency or other serious underlying chronic disease. The prevention of and potential long-term effects from bronchiolitis are beyond the scope of this statement but are well described in the literature and other statements from the Canadian Paediatric Society.[4][6]

Diagnosis

Bronchiolitis is a clinical diagnosis based on a directed history and physical examination. Bronchiolitis may present with a wide range of symptoms and severity, from a mild upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) to impending respiratory failure (Table 1). Bronchiolitis typically presents with a first episode of wheezing before the age of 12 months. The course begins with a two-to-three-day viral prodrome of fever, cough and rhinorrhea progressing to tachypnea, wheeze, crackles and a variable degree of respiratory distress. Signs of respiratory distress may include grunting, nasal flaring, indrawing, retractions or abdominal breathing. There may or may not be a history of exposure to an individual with a viral URTI.

While the majority of wheezing infants who present acutely between November and April most likely have viral bronchiolitis, clinicians should consider a broad differential diagnosis, especially in patients with atypical presentations such as severe respiratory distress, no viral URTI symptoms and/or frequent recurrences (Table 2).[7] Physical examination findings of importance include increased respiratory rate, signs of respiratory distress, and crackles and wheezing on auscultation. Measurement of oxygen saturation often shows decreased saturation levels. Signs of dehydration may be present if respiratory distress has been sufficient to interfere with feeding.

Investigations

Diagnostic studies are not indicated for most children with bronchiolitis (Table 3). Tests are often unhelpful and can lead to unnecessary admissions, further testing and ineffective therapies. Evidence-based reviews have not supported the use of diagnostic testing in typical cases of bronchiolitis.[1][7]

Chest radiograph (CXR) of infants with bronchiolitis often reveals nonspecific, patchy hyperinflation and areas of atelectasis,[4] which may be misinterpreted as consolidation. This can lead to increased and inappropriate use of antibiotics.[15] In infants with typical bronchiolitis, a recent prospective study found CXR findings inconsistent with bronchiolitis in only two of 265 infants, and in no case did the results change acute management.[16] While routine CXR is not supported by current evidence, it should be considered when the diagnosis of bronchiolitis is unclear, the rate of improvement is not as expected or the severity of disease raises other diagnostic possibilities such as bacterial pneumonia.

Nasopharyngeal swabs for respiratory viruses generally are not helpful from a diagnostic perspective and do not alter management in most cases. They are not routinely recommended unless required for infection control purposes, or in high risk patients where the results will influence treatment decisions (e.g., performance of additional tests, hospitalization, or prescription of Oseltamivir for influenza).[17][18]

Complete blood count has not been found to be useful in predicting serious bacterial infections (SBI).[19]

Bacterial cultures: The incidence of concomitant SBI in febrile infants with bronchiolitis is low.[7] Systematic review data indicate that urinary tract infections (UTIs) are the most common SBI in infants with bronchiolitis and aged <90 days.[20] While overall rates of UTI in this population are 3.1%, when positive urinalysis results (pyuria or nitrites) are appropriately incorporated into the definition[21] of UTI, the UTI prevalence decreases to 0.8%, a rate unchanged by the infant’s RSV status.[22] Rates of bacteremia in this population are 0.2% to 1.4%, with no cases of meningitis detected via systematic review.[20] Routine screening for SBI, including urinalysis, in infants with bronchiolitis is not indicated, but rather should be performed based on clinical judgement. It should be noted that this position statement does not address the neonatal population, for whom rates of SBI may be higher.[23]

| Table 3 | |

| Role of diagnostic studies in typical cases of bronchiolitis | |

| Type | Specific indications |

|

Chest radiograph Nasopharyngeal swabs Complete blood count Blood gas Bacterial cultures (blood, urine, cerebral spinal fluid [CSF]) |

Only if severity or course suggests alternate diagnosis (Table 2) Only if required for cohorting admitted patients Generally not helpful in diagnosis or monitoring of routine cases Only if concerned about potential respiratory failure Not recommended routinely; may be indicated based on clinical judgement |

Decision to admit

The decision to admit should be based on clinical judgment and consider the infant’s respiratory status, ability to maintain adequate hydration, risk for progression to severe disease and the family’s ability to cope (Tables 4 and 5). Physicians should keep in mind that the disease tends to worsen over the first 72 h when deciding whether to hospitalize.[24] Clinical scores and individual findings on physical examination cannot be relied on in isolation to predict outcomes. Severity scoring systems exist; however, none are widely used and few have demonstrated predictive validity. Respiratory rate, subcostal retractions and oxygen need may be the most helpful parameters used in the various bronchiolitis severity scores.[25]

Repeated observations over a period of time are important because there may be significant temporal variability. Consistent predictors of hospitalization in outpatient populations[7][26] include age (<3 months) and history of prematurity (<35 weeks’ gestation). Another study found that patients with any three of the following four factors – decreased hydration, accessory muscle score >6 of 9, O2 saturation <92% and respiratory rate >60 breaths/min – had a 13-fold increase in hospitalization rate.[27]

The role of pulse oximetry in clinical decision-making remains controversial. While oxygen saturations of <94% are associated with a more than five-fold increase in likelihood of admission,[26] it is important to recognize that setting arbitrary thresholds for oxygen therapy will influence admission rates. This effect was illustrated in a survey of emergency department physicians that showed a significant increase in the likelihood of recommending admission by simply reducing saturation from 94% to 92% in clinical vignettes.[28]

| Table 4 |

| Groups at higher risk for severe disease |

|

Infants born prematurely (<35 weeks’ gestation) <3 months of age at presentation Hemodynamically significant cardiopulmonary disease Immunodeficiency |

| Table 5 |

| Guidelines for admission may include |

|

Signs of severe respiratory distress (eg, indrawing, grunting, RR >60/min) Supplemental O2 required to keep saturations >90% Dehydration or history of poor fluid intake Cyanosis or history of apnea Infant at high risk for severe disease (Table 4) Family unable to cope |

Management

Bronchiolitis is a self-limiting disease. Most children have mild disease and can be managed with supportive care at home. For those requiring admission, supportive care with assisted feeding, minimal handling, gentle nasal suctioning and oxygen therapy still forms the mainstay of treatment (Table 6).

Therapies recommended based on evidence

Oxygen

Supplemental oxygen therapy is a mainstay of treatment in hospital. Oxygen should be administered if saturations fall below 90% and used to maintain saturations at ≥90%.[1] To minimize handling, oxygen is usually administered via nasal cannula, face mask or a head box.

A recent alternative is heated, humidified, high-flow nasal cannula (HHHFNC) oxygen therapy. There is increasing evidence this mode of non-invasive respiratory support is safe, and may reduce the need for CPAP and mechanical ventilation in moderate and severe bronchiolitis. [29]-[34] Currently, there is insufficient evidence to support its routine use in bronchiolitis.[35] Ongoing studies investigating use of this therapy for bronchiolitis will likely inform practice in the near future.[36]

Hydration

Some degree of fluid supplementation is required in 30% of hospitalized patients with bronchiolitis.[37]

Frequent feeds should be encouraged and breastfeeding supported; both may be facilitated by providing supplemental oxygen. Infants with a respiratory rate >60 breaths/min, particularly those with nasal congestion, may have an increased risk of aspiration and may not be safe to feed orally.[11] When supplemental fluids are required, a recent randomized trial found nasogastric (NG) and intravenous (IV) routes to be equally effective, with no difference in length of hospital stay.[38] NG insertion may require fewer attempts and have a higher success rate than IV placement. If NG bolus feeds are not tolerated, slow continuous feeds are an option. If the IV route is used, isotonic fluids (0.9% NaCl/5% dextrose) are preferred for maintenance, with regular monitoring of serum Na because of the risk of hyponatremia.[39][40]

Therapies for which evidence is equivocal

Epinephrine

Some studies have shown that epinephrine nebulization may be effective for reducing hospital admissions,[41] and one trial showed that combined treatment with epinephrine and steroids reduced admissions.[42] However, the evidence remains insufficient to support routine use of epinephrine in the emergency department. It may be reasonable to administer a dose of epinephrine and carefully monitor clinical response; however, unless there is clear evidence of improvement, continued use is not appropriate. A systematic review of 19 studies evaluating the use of epinephrine in bronchiolitis shows no effect on length of hospital stay[41] and there is insufficient evidence to support its routine use in admitted patients.

Nasal suctioning

As for many long-standing and commonly used therapies for children, there is scant evidence supporting the use of nasal suctioning in the management of bronchiolitis. While it appears that suctioning mucus out of blocked nares would be a harmless procedure, one recent study has suggested that deep suctioning and long intervals between suctioning are associated with increased length of stay.[43] This suggests that if suctioning is performed, it should be done superficially and reasonably frequently.

Combination epinephrine and dexamethasone

One publication from the Pediatric Emergency Research Canada group found an unexpected synergism between the administration of nebulized epinephrine with oral dexamethasone. The combination appeared to result in a reduced hospitalization rate, with a number needed to treat of 11. However, these results were rendered nonsignificant when adjusted for multiple comparisons.[42] More research is needed to assess the role of combination therapies. Pending better definition of its risks and benefits, this combination is not recommended for the therapy of otherwise healthy children with bronchiolitis.

Therapies not recommended based on evidence

Salbutamol (Ventolin; GlaxoSmithKline, USA)

Children with bronchiolitis present with a wheeze that is clinically similar to that observed with asthma. However, the pathophysiology of bronchiolitis is such that the airways are obstructed rather than constricted.[7][46] Furthermore, infants appear to have inadequate β-agonist lung receptor sites and immature bronchiolar smooth muscles.[47] While studies have shown small improvements in clinical scores, bronchodilators have not been shown to improve O2 saturation, do not reduce admission rates and do not shorten the duration of stay in hospital.[46] When the diagnosis of bronchiolitis is clear, a trial of salbutamol is not recommended.[11]

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone, prednisone or inhaled glucocorticoids, are not associated with a clinically significant improvement in disease, as measured by reduction in clinical scores, rates of hospitalization and length of hospital stay.[1][24][49][50] Furthermore, any small benefit that corticosteroids may offer must be weighed against the risks of steroid treatment. Corticosteroids are not recommended for routine use in bronchiolitis.

Antibiotics

Many children with acute bronchiolitis are prescribed an antibiotic, often for infections diagnosed in the absence of stringent diagnostic criteria (e.g., acute otitis media without a middle ear effusion and bulging tympanic membrane).[51] However, true bacterial infection in otherwise healthy children with bronchiolitis is exceedingly rare.[50] Research on the role of antibiotics in bronchiolitis is limited and has, to date, failed to identify any benefit. Currently, antibiotics should not be used except in cases in which there is clear evidence or strong suspicion of a secondary bacterial infection.[11]

Antivirals

Antiviral therapies, such as ribavirin, are expensive, cumbersome to administer, provide limited benefit and are potentially toxic to care providers and, thus, are not recommended for the routine treatment of bronchiolitis in otherwise healthy children.[1] In patients with or at risk for particularly severe disease, antivirals could be considered, but this decision should be made on an individual basis in consultation with appropriate subspecialists.[1][52][53]

3% hypertonic saline nebulization

It has been hypothesized that hypertonic saline increases mucociliary clearance and rehydrates airway surface liquid, with questions as to impact on inpatient length of stay.[44] Recent evidence from meta-analysis, which accounted for important variation among included studies, does not support the use of hypertonic saline.[45] In a typical North American population, 3% hypertonic saline has no impact on length of stay and should not be used routinely.

Chest physiotherapy

Nine clinical trials comparing physiotherapy with no treatment were reviewed.[54] Neither vibration and percussion nor passive expiratory techniques were shown to improve clinical scores or to reduce hospital stay or duration of symptoms. Chest physiotherapy is not recommended for the treatment of bronchiolitis.[11][54]

Cool mist therapies or aerosol therapy with isotonic saline

Cool mist and other aerosol therapies have been used for some time to manage bronchiolitis, with scant evidence supporting their efficacy. A recent Cochrane review concluded that there is no evidence supporting or refuting the use of cool mist and other aerosols for managing bronchiolitis.[55]

Other therapies used for critically ill infants with severe bronchiolitis, such as helium/oxygen, nasal continuous positive airway pressure, mechanical ventilatory support and surfactant, are beyond the scope of this statement.[56]-[58]

Monitoring in hospital

Patients with bronchiolitis should be cared for in an environment with ready access to suction equipment and supplemental oxygen that can be delivered at measurable rates. Close attention must be devoted to infection control processes. To reduce nosocomial transmission, patients with bronchiolitis (regardless of specific viral etiology) should be cared for using droplet and contact precautions (including mask and eye protection for staff), optimally in a single room.[2][8][59][60]

The most important component of monitoring infants admitted with bronchiolitis is regular and repeated clinical assessments by staff with appropriate expertise in the respiratory assessment of young children. Monitoring should include assessment and documentation of respiratory rate, work of breathing, oxygen saturation, findings on auscultation and general condition, including feeding and hydration status. Scoring tools have been developed in an attempt to standardize assessments and facilitate communication among caregivers. However, there is insufficient evidence of impact on patient outcomes to recommend using any specific tool.[61]-[63]

The use of electronic monitoring of vital signs and oxygen saturation should not be considered a substitute for regular clinical assessments by experienced personnel. Furthermore, there is growing evidence to suggest that continuous monitoring may prolong length of stay, particularly if staff react to normal transient dips in oxygen saturation or changes in heart and respiratory rates with interventions such as restarting oxygen therapy.[64] The accuracy of pulse oximetry is relatively poor, particularly at saturations <90%.[65]

The primary rationale for cardiac and respiratory monitoring is to detect episodes of apnea requiring intervention. The incidence of apnea in RSV bronchiolitis may be lower than previously believed. In a large study involving 691 infants <6 months of age, only 2.7% had documented apnea, and all had risk criteria of either a previous apneic episode or young age (<1 month or <48 weeks postconception in premature infants).[66] Continuous electronic cardiac and respiratory monitoring may be useful for high-risk patients in the acute phase of illness but are not necessary for the vast majority of patients with bronchiolitis.

Determining oxygen saturation can aid in decisions about escalating or weaning oxygen therapy. However, the issue of continuous versus intermittent monitoring of oxygen saturation is controversial. Continuous monitoring may be more sensitive for identifying patients who are deteriorating and need escalation of treatment. At the same time, many healthy infants exhibit typical transient O2 saturation dips[67][68] and length of stay may be prolonged if oxygen therapy is based on arbitrary saturation targets. Several clinical trials currently underway are attempting to determine best practices in this area. Until clear evidence is available, a reasonable approach is to adjust the intensity of oxygen saturation monitoring according to the patient’s clinical status. Continuous saturation monitoring is appropriate for high-risk patients early in the course of disease, while intermittent monitoring is most appropriate for lower-risk patients and for all patients once they are feeding well, weaning from supplemental oxygen and showing improvement in work of breathing.

|

|

|

Figure 1) Algorithm for medical management of bronchiolitis. Adapted from American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Emergency Medicine

https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/Committees-Councils-Sections/Section-on-Emergency-Medicine/Documents/SOEM-AAPSOEMCOQTBronchiolitisGuideline.pdf |

Readiness for discharge from hospital should be based on clinical judgement and consider the family’s ability to recognize and respond to signs of deterioration. In general, patients may be safely discharged from hospital once they are improving clinically and meet criteria listed in Table 7.

Conclusions

The optimal management of bronchiolitis for otherwise healthy children has been debated for some time. In a seminal review published in 1965, the admonition was made to use patience and avoid unnecessary and futile therapy.[69] This prudent advice has been ignored frequently over the past 50 years.[70] The optimal management of bronchiolitis in otherwise healthy children remains nested, first and foremost, in excellent supportive care. While trials investigating other modalities are ongoing, the health care provider is reminded that ‘primum non nocere’ should remain the key dictum in the treatment of otherwise healthy children with bronchiolitis.

Recommendations

- Bronchiolitis is a clinical diagnosis based on history and physical examination. Diagnostic studies, including chest radiograph, blood tests and viral/bacterial cultures, are not recommended in typical cases.

- The decision to admit to hospital should be based on clinical judgment, factoring in the risk for progression to severe disease, respiratory status, ability to maintain adequate hydration and the family’s ability to cope at home.

- Management is primarily supportive including hydration, minimal handling, gentle nasal suctioning and oxygen therapy.

- Both NG and IV routes are acceptable for supplemental hydration. When IV fluids are used, an isotonic solution (0.9% NaCl/5% dextrose) is recommended, together with routine monitoring of serum Na.

- The use of epinephrine is not recommended in routine cases. If a trial of epinephrine inhalation is attempted in the emergency department, ongoing treatment should only occur if there are clear signs of clinical improvement.

- Current evidence does not support the use of hypertonic 3% sodium chloride in routine cases of bronchiolitis.

- The use of salbutamol (Ventolin) is not recommended in routine cases.

- The use of corticosteroids is not recommended in routine cases.

- The use of antibiotics is not recommended unless there is evidence, or strong suspicion of an underlying bacterial infection.

- The use of chest physiotherapy is not recommended.

- Thoughtful use of oxygen saturation monitoring in hospitalized patients is recommended. Continuous saturation monitoring may be indicated for high-risk children in the acute phase of illness, and intermittent monitoring or spot checks are appropriate for lower-risk children and patients who are improving clinically.

Acknowledgements

This position statement was reviewed by the Community Paediatrics Committee and the Hospital Paediatrics and Emergency Medicine Sections of the Canadian Paediatric Society, as well as by representatives of the College of Family Physicians of Canada.

CPS ACUTE CARE COMMITTEE

Members: Laurel Chauvin-Kimoff MD (Chair), Isabelle Chevalier MD (Board Representative), Catherine A Farrell MD, Jeremy N Friedman MD, Angelo Mikrogianakis MD (past Chair), Oliva Ortiz-Alvarez MD

Liaisons: Dominic Allain MD, CPS Paediatric Emergency Medicine Section; Tracy MacDonald BScN, Canadian Association of Paediatric Health Centres; Jennifer M Walton MD, CPS Hospital Paediatrics Section

CPS DRUG THERAPY AND HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES COMMITTEE

Members: Mark L Bernstein MD, François Boucher MD (Board Representative), Ran D Goldman MD, Geer’t Jong MD, Philippe Ovetchkine MD, Michael J Rieder MD (Chair),

Liaisons: Daniel Louis Keene MD, Health Canada; Doreen Matsui MD (past Chair)

Principal authors: Jeremy N Friedman MD, Michael J Rieder MD, Jennifer M Walton MD

Updated by Carolyn Beck, Kyle McKenzie and Laurel Chauvin-Kimoff

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Subcommittee on Diagnosis and Management of Bronchiolitis. Diagnosis and management of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 2006;118(4):1774-93.

- Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, et al. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med 2009;360(6):588-98.

- Henrickson KJ. Advances in the laboratory diagnosis of viral respiratory disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004;23(1 Suppl):S6-10.

- Smyth RL, Openshaw PJ. Bronchiolitis. Lancet 2006;368(9532):312-22.

- Paranhos-Baccalà G, Komurian-Pradel F, Richard N, Vernet G, Lina B, Floret D. Mixed respiratory virus infections. J Clin Virol 2008;43(4):407-10.

- Robinson JL, Le Saux N; Canadian Paediatric Society, Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee. Preventing hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus infections. Paediatr Child Health 2015;20(6):321-6.

- Zorc JJ, Hall CB. Bronchiolitis: Recent evidence on diagnosis and management. Pediatrics 2010;125(2):342-9.

- Shay DK, Holman RC, Newman RD, Liu LL, Stout JW, Anderson LJ. Bronchiolitis-associated hospitalizations among US children, 1980-1996. JAMA 1999;282(15):1440-6.

- Stang P, Brandenburg N, Carter B. The economic burden of respiratory syncytial virus-associated bronchiolitis hospitalizations. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001;155(1):95-6.

- Leader S, Yang H, DeVincenzo J, Jacobson P, Marcin JP, Murray DL. Time and out-of-pocket costs associated with respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization of infants. Value Health 2003;6(2):100-6.

- Ralston SL, Lieberthal AS, Meissner HC, et al. Clinical practice guideline: The diagnosis, management and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 2014;134(5):e1474-e1502.

- Christakis DA, Cowan CA, Garrison MM, Molteni R, Marcuse E, Zerr DM. Variation in inpatient diagnostic testing and management of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 2005;115(4):878-84.

- Todd J, Bertoch D, Dolan S. Use of a large national database for comparative evaluation of the effect of a bronchiolitis/viral pneumonia clinical care guideline on patient outcome and resource utilization. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156(11):1086-90.

- Parikh K, Hall M, Teach SJ. Bronchiolitis management before and after the AAP guidelines. Pediatrics 2014;133(1):e1-7.

- Swingler GH, Hussey GD, Zwarenstein M. Randomised controlled trial of clinical outcome after chest radiograph in ambulatory acute lower-respiratory infection in children. Lancet 1998;351(9100):404-8.

- Schuh S, Lalani A, Allen U, et al. Evaluation of the utility of radiography in acute bronchiolitis. J Pediatr 2007;150(4):429-33.

- Gill PJ, Richardson SE, Ostrow O, et al. Testing for respiratory viruses in children: To swab or not to swab. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(8):798-804.

- Mansbach JM, Piedra PA, Teach SJ, et al. Prospective, multicenter study of viral etiology and hospital length-of-stay in children with severe bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012;166(8):700-6.

- Purcell K, Fergie J. Lack of usefulness of an abnormal white blood cell count for predicting a concurrent serious bacterial infection in infants and young children hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2007;26(4):311-5.

- Ralston S, Hill V, Waters A. Occult serious bacterial infection in infants younger than 60 to 90 days with bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011;165(10):951-6.

- Roberts KB; Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. Urinary tract infection: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of the initial UTI in febrile infants and children 2 to 24 months. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3):595-610. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1330

- McDaniel CE, Ralston S, Lucas B, Schroeder AR. Association of diagnostic criteria with urinary tract infection prevalence in bronchiolitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. Published online: January 28, 2019. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5091

- Bonadio W, Huang F, Natesan S, et al. Meta-analysis to determine risk for serious bacterial infection in febrile outpatient neonates with RSV infection. Pediatr Emerg Care 2016;32(5):286-9.

- Wainwright C. Acute viral bronchiolitis in children: A very common condition with few therapeutic options. Paediatr Respir Rev 2010;11(1):39-45; quiz 45.

- Destino L, Weisgerber MC, Soung P, et al. Validity of respiratory scores in bronchiolitis. Hosp Pediatr 2012;2(4):202-9.

- Mansbach JM, Clark S, Christopher NC, et al. Prospective multicenter study of bronchiolitis: Predicting safe discharges from the emergency department. Pediatrics 2008;121(4):680-8.

- Parker MJ, Allen U, Stephens D, Lalani A, Schuh S. Predictors of major intervention in infants with bronchiolitis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2009;44(4):358-63.

- Mallory MD, Shay DK, Garrett J, Bordley WC. Bronchiolitis management preferences and the influence of pulse oximetry and respiratory rate on the decision to admit. Pediatrics 2003;111(1):e45-51.

- Kepreotes E, Whitehead B, Attia J, et al. High-flow warm humidified oxygen versus standard low-flow nasal cannula oxygen for moderate bronchiolitis (HFWHO RCT): An open, phase 4, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017;389(10072):930-9.

- Mayfield S, Bogossian F, O’Malley L, Schibler A. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy for infants with bronchiolitis: Pilot study. J Paediatr Child Health 2014;50(5):373-8.

- McKiernan C, Chua LC, Visintainer PF, Allen H. High-flow nasal cannulae therapy in infants with bronchiolitis. J Pediatr 2010;156(4):634-8.

- Hilliard TN, Archer N, Laura H, et al. Pilot study of vapotherm oxygen delivery in moderately severe bronchiolitis. Arch Dis Child 2012;97(2):182-3.

- ten Brink F, Duke T, Evans J. High-flow nasal prong oxygen therapy or nasopharyngeal continuous positive airway pressure for children with moderate-to-severe respiratory distress? Pediatr Crit Care Med 2013;14(7):e326-31.

- Bressan S, Balzani M, Krauss B, Pettenazzo A, Zanconato S, Baraldi E. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen for bronchiolitis in a pediatric ward: A pilot study. Eur J Pediatr 2013;172(12):1649-56.

- Beggs S, Wong ZH, Kaul S, Ogden KJ, Walters JA. High-flow nasal cannula therapy for infants with bronchiolitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(1):CD009609.

- Franklin D, Dalziel S, Schlapbach LJ, et al. Early high-flow nasal cannula therapy in bronchiolitis, a prospective randomised control trial (protocol): A Paediatric Acute Respiratory Intervention Study (PARIS). BMC Pediatr 2015;15:183.

- Kennedy N, Flanagan N. Is nasogastric fluid therapy a safe alternative to the intravenous route in infants with bronchiolitis? Arch Dis Child 2005;90(3):320-1.

- Oakley E, Borland M, Neutze J, et al. Nasogastric hydration versus intravenous hydration for infants with bronchiolitis: A randomised trial. Lancet Respir Med 2013;1(2):113-20.

- Friedman JN; Canadian Paediatric Society, Acute Care Committee. Risk of acute hyponatremia in hospitalized children and youth receiving maintenance intravenous fluids. Paediatr Child Health 2013;18(2):102-7.

- Wang J, Xu E, Xiao Y. Isotonic versus hypotonic maintenance IV fluids in hospitalized children: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2014;133(1):105-13.

- Hartling L, Bialy LM, Vandermeer B, et al. Epinephrine for bronchiolitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011(6):CD003123.

- Plint AC, Johnson DW, Patel H, et al. Epinephrine and dexamethasone in children with bronchiolitis. N Engl J Med 2009;360(20):2079-89.

- Mussman GM, Parker MW, Statile A, Sucharew H, Brady PW. Suctioning and length of stay in infants hospitalized with bronchiolitis. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167(5):414-21.

- Zhang L, Mendoza-Sassi RA, Wainwright C, Klassen TP. Nebulised hypertonic saline solution for acute bronchiolitis in infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(7):CD006458.

- Brooks CG, Harrison WN, Ralston SL. Association between hypertonic saline and hospital length of stay in acute viral bronchiolitis: A reanalysis of 2 meta-analyses. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170(6):577-84.

- Gadomski AM, Scribani MB. Bronchodilators for bronchiolitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(6):CD001266.

- Anil AB, Anil M, Saglam AB, Cetin N, Bal A, Aksu N. High volume normal saline alone is as effective as nebulized salbutamol-normal saline, epinephrine-normal saline, and 3% saline in mild bronchiolitis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2010;45(1):41-7.

- Fernandes RM, Bialy LM, Vandermeer B, et al. Glucocorticoids for acute viral bronchiolitis in infants and young children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(6):CD004878.

- Corneli HM, Zorc JJ, Mahajan P, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of dexamethasone for bronchiolitis. N Engl J Med 2007;357(4):331-9.

- Farley R, Spurling GK, Eriksson L, Del Mar CB. Antibiotics for bronchiolitis in children under two years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(10):CD005189.

- Le Saux N, Robinson JL, Canadian Pediatric Society, Saux N Le, Robinson JL, Society CP. Management of acute otitis media in children six months of age and older. Paediatr Child Health. 2016 Jan;21(1):39–50.

- Li L, Avery R, Budev M, Mossad S, Danziger-Isakov L. Oral versus inhaled ribavirin therapy for respiratory syncytial virus infection after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2012;31(8):839-44.

- Turner TL, Kopp BT, Paul G, Landgrave LC, Hayes D Jr, Thompson R. Respiratory syncytial virus: Current and emerging treatment options. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2014;6:217-25.

- Roqué i Figuls M, Giné-Garriga M, Granados Rugeles C, Perrotta C, Vilaro J. Chest physiotherapy for acute bronchiolitis in paediatric patients between 0 and 24 months old. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;(2):CD004873.

- Umoren R, Odey F, Meremikwu MM. Steam inhalation or humidified oxygen for acute bronchiolitis in children up to three years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011(1):CD006435.

- Essouri S, Laurent M, Chevret L, et al. Improved clinical and economic outcomes in severe bronchiolitis with pre-emptive nCPAP ventilatory strategy. Intensive Care Med 2014;40(1):84-91.

- Essouri S, Durand P, Chevret L, et al. Optimal level of nasal continuous positive airway pressure in severe viral bronchiolitis. Intensive Care Med 2011;37(12):2002-7.

- Donlan M, Fontela PS, Puligandla PS. Use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in acute viral bronchiolitis: A systematic review. Pediatr Pulmonol 2011;46(8):736-46.

- Madge P, Paton JY, McColl JH, Mackie PL. Prospective controlled study of four infection-control procedures to prevent nosocomial infection with respiratory syncytial virus. Lancet 1992;340(8827):1079-83.

- Krasinski K, LaCouture R, Holzman RS, Waithe E, Bonk S, Hanna B. Screening for respiratory syncytial virus and assignment to a cohort at admission to reduce nosocomial transmission. J Pediatr 1990;116(6):894-898.

- Liu LL, Gallaher MM, Davis RL, Rutter CM, Lewis TC, Marcuse EK. Use of a respiratory clinical score among different providers. Pediatr Pulmonol 2004;37(3):243-8.

- Rödl S, Resch B, Hofer N, et al. Prospective evaluation of clinical scoring systems in infants with bronchiolitis admitted to the intensive care unit. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2012;31(10):2667-72.

- Duarte-Dorado DM, Madero-Orostegui DS, Rodriguez-Martinez CE, Nino G. Validation of a scale to assess the severity of bronchiolitis in a population of hospitalized infants. J Asthma 2013;50(10):1056-61.

- Schroeder AR, Marmor AK, Pantell RH, Newman TB. Impact of pulse oximetry and oxygen therapy on length of stay in bronchiolitis hospitalizations. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004;158(6):527-30.

- Ross PA, Newth CJ, Khemani RG. Accuracy of pulse oximetry in children. Pediatrics 2014;133(1):22-9.

- Willwerth BM, Harper MB, Greenes DS. Identifying hospitalized infants who have bronchiolitis and are at high risk for apnea. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48(4):441-7.

- Hunt CE, Corwin MJ, Lister G, et al. Longitudinal assessment of hemoglobin oxygen saturation in healthy infants during the first 6 months of age. Collaborative Home Infant Monitoring Evaluation (CHIME) Study Group. J Pediatr 1999;135(5):580-6.

- Poets A, Urschitz MS, Poets CF. Intermittent hypoxia in supine versus side position in term neonates. Pediatr Res 2009;65(6):654-6.

- Wright FH, Beem MO. Diagnosis and treatment: Management of acute viral bronchiolitis in infancy. Pediatrics 1965;35:334-7.

- Schroeder AR, Mansbach JM. Recent evidence on the management of bronchiolitis. Curr Opin Pediatr 2014;26(3):328-33.

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.